This week’s contributing author, Caroline Gil Rodríguez, is a time-based media conservator and archivist from Puerto Rico. Caroline was previously an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her areas of interest include media art technologies, the circulation of time-based media art in Latin America and the Caribbean, low-cost open-source solutions for digital preservation and collectivism.

Exhibiting video games in an art museum

Should video games be exhibited alongside a collection of exceptional modern paintings? And if so, what is the proper way to display video games within an art historical context? This line of inquiry became the seedbed of acquisition of 14 video games in 2012, followed by an additional 2013 accession of 6 more games shepherded by MoMA’s Architecture and Design curatorial department helmed by Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator of Architecture and Design, and Director, Research and Development.

Resistance to new mediums and forms being welcomed into established art world markets have storied, historical precedent. Both film and tape-based video artworks have been gradually absorbed by fine art collecting institutions thanks in large part to the circuits and practices established by film and video distributors such as EAI, Video Data Bank, and Canyon Cinema, independent media festivals, and the pioneering work of media and performance art curators who introduced these works to museums. Video games share characteristics and features found in other media art practices such as performance art and interactive installations, where narratives and complex user behavior and interaction are coupled with rich visual stimuli and aesthetics. As Antonelli notes on MoMA’s Inside/Out blog, a designed interactive audio-visual experience is expressed through the sophistication and dynamism of the game’s code:

The space in which the game exists and evolves—built with code rather than brick and mortar—is an architecture that is planned, designed, and constructed according to a precise program, sometimes pushing technology to its limits in order to create brand new degrees of expressive and spatial freedom.[1]

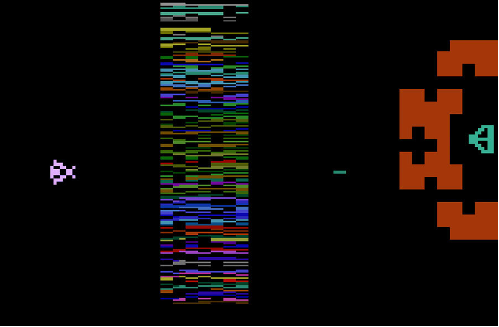

One of the video games included in the 2013 acquisition was Yars’ Revenge, developed for the Atari 2600 in 1981. In the game, the hero-protagonist—called a Yar—is an insect-like creature that must nibble or shoot through a barrier and destroy the evil Qotile who waits on the other side of the barricade. The game was created by Howard Scott Warshaw, a former game designer who worked for Atari in the early 1980s, and who famously designed and programmed other noteworthy games such as Raiders of the Lost Ark, and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Howard Scott Warshaw, Yars’ Revenge, 1982, Medium: video game software, Publisher: Atari Inc. 705.2013

For that acquisition, MoMA received a ROM (Read Only Memory) of the game. These files contain a copy of the read-only memory chip that holds an arcade game’s system (or main) board. The museum also obtained loose documentation including audio files for the game’s distinctive soundtrack, images of the original game cartridge, and artwork. When Yars’ Revenge was exhibited in 2012, the game required a desktop Lenovo computer that ran a Stella emulator in order to be executed. An emulator can replicate the behavior of old video game consoles such as the Atari 2600, and through this technique users can play vintage video games on contemporary devices. Emulation is a popular hobbyist and community driven mode of video game preservation. Open source emulators such as MAME (Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator) were initially developed to recreate the hardware of arcade game systems and to preserve the ability to play these older generation video games and others like it. These open source emulators are diligently maintained and supported by a community of dedicated game enthusiasts. In the 2013 Applied Design exhibition, the video games were displayed on plasma screens mounted flush to the wall. The game’s original housing was eschewed in favor of shelf-like control units, with buttons, joysticks, and headphones that protrude below the screens. Barring the typical arcade setting or home console exterior, the game’s design is isolated and placed front and center, inviting an engaged experience extricated from nostalgia.

Fast forward to 2019 when Yars’ Revenge was added to the checklist for the MoMA exhibition Energy, which sought to showcase the technological advances of the past decades. The work and its equipment were brought out from storage and to the bench of MoMA’s media conservation team, where I was working at the time. I was assigned to come up with a way to display the game, refraining from the Lenovo desktop computer, and minimizing the footprint of what was essentially a way to playback or run the game’s emulator. For this task, I first had to research if it was possible to run the provided ROM on a Raspberry Pi, a line of small, single-board computers, and price out what equipment I needed for the build. My intention was to test and mockup a new setup on my desk and compare the 2012 version to the 2019 installation to make sure that any significant properties were not lost in the upgrade.

After researching what materials I needed, I decided to build a retropie machine using a CanaKit Raspberry Pi B+ kit. RetroPie is built upon Raspbian (the Raspberry Pi GNU/linux Operating System), EmulationStation (a graphical and themeable launcher for various emulators) and RetroArch (a free, open-source and cross-platform front-end for emulators, game engines, video games, media players and other applications). RetroPie is a customizable open-source bundle of emulation software that is very popular within the vintage gaming community. Configuring and programming the Raspberry Pi took weeks of trial and testing, and many excursions to online forums. Because emulators marry hardware and software components, configuring the Raspberry Pi also meant that I had to map the available hardware (a keyboard and the joystick) to the emulator. In this way, the emulator translates and up/down key to the up/down motion of a joystick. I also wanted to customize the emulator, so that as soon as one game ended, it would automatically start a new game.The auto start function was key, as we didn’t want a game to end and return to a RetroPie ‘backend’ or other configuration menus.

To scrutinize the success of my approach, I ran the newer RetroPie version side by side with the 2012 version running the Stella emulator on the Lenovo PC computer. I invited some of my colleagues to play with the game and visually assessed that there were no changes in rendering, color, aspect ratio, etc. In retrospect, I would have liked to do this assessment in a more systematic, methodical way and carefully look at attributes such as interaction modes, speed of execution, display, access, and so forth, display attributes (pixel size and shape, color, dimensionality), device and peripheral characteristics, multi-user aspects, version and other configuration details. But the work had to be installed and I’m happy to say that there were no issues for the duration of the 2019 exhibition save for the joysticks continually breaking due to mechanical damage since they are made of cheap plastic and coil springs.

Although unconventional, choosing an emulation strategy focuses possible conservation actions on the software environment and their relation to and interaction with hardware. Cases such as the 2004 Guggenheim exhibition Seeing Double: Emulation in Theory and Practice presented original art installations paired side-by-side with their emulated versions, yet emulation as a conservation strategy continues to be inconspicuous to the average museum goer. Emulation takes research, time to perfect, and is not always an inexpensive avenue. By replacing at-risk components such as aging carriers (i.e. video game cartridges and consoles) and translating the work to a more stable technology, we are able to ensure and adhere to the tenets of art conservation: minimal intervention, reversibility, and informed decision making.

[1] Antonelli, Paola, ‘Video Games: 14 in the Collection, for Starters’ MoMA Inside/out Blog, November 29, 2012, https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2012/11/29/video-games-14-in-the-collection-for-starters/

[…] This week’s returning author, Caroline Gil Rodríguez, is a time-based media conservator and archivist from Puerto Rico. Caroline was previously an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her areas of interest include media art technologies, the circulation of time-based media art in Latin America and the Caribbean, low-cost open-source solutions for digital preservation and collectivism. To read Part 1 of this series, click HERE. […]