This week’s returning author, Caroline Gil Rodríguez, is a time-based media conservator and archivist from Puerto Rico. Caroline was previously an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her areas of interest include media art technologies, the circulation of time-based media art in Latin America and the Caribbean, low-cost open-source solutions for digital preservation and collectivism. To read Part 1 of this series, click HERE.

The Solari Split-Flap Display

The distinctive fluttering action of a split-flap board—a typographic display of rotating metal flaps with silk-screened printed characters—is a distinguishable attribute of the Split-Flap Board Flight Information Display System. Associated with the advent of global travel of the 20th century, split flap displays became a symbol correlated to the prestige industry and growing economy of the “golden-age” of destination travel. Beginning in 1956, the displays were ubiquitous in railway stations and international airports: the centerpiece of crowded transit hubs. The display systems were designed and manufactured by Solari di Udine, a family run company established in Northern Italy in 1725 that originally produced tower and wall clocks. The company designed the boards with great care and attention to detail, scrutinizing the mechanics and legibility of the board flaps conventionally printed in Gill Sans bold or Helvetica typefaces.

While the mechanical signs are fast disappearing from spaces of global logistics, and their legacy manufacturers have moved on to LCD screens, the old analog apparatae have inherited new communicative and aesthetic functions.[1]

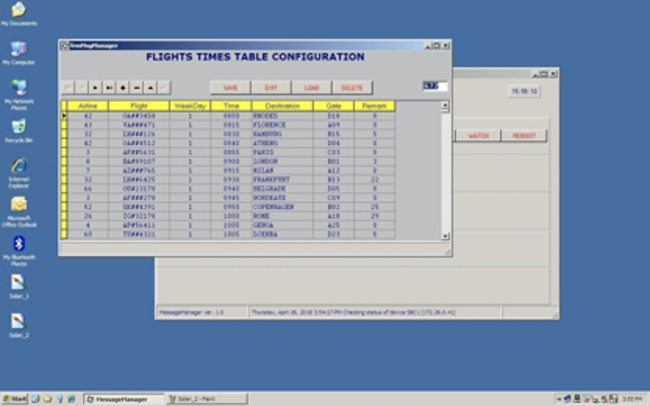

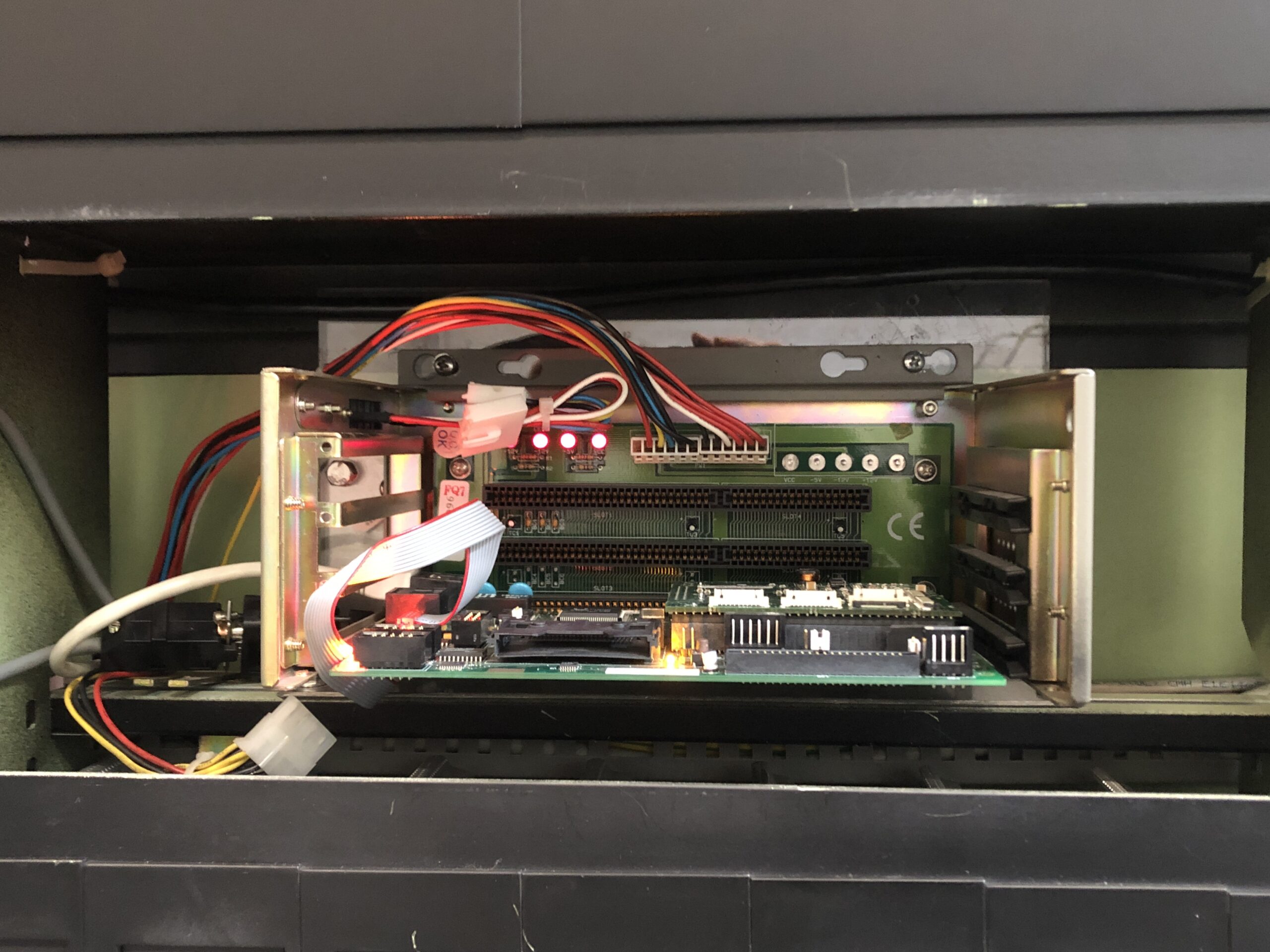

One of the new functions Mattern alludes to is the transformation of the Solari Split-Flap Board from utilitarian display device to a design object, prominently displayed at one the US’s leading modern art museums. The Solari Split-Flap Board model that was acquired by MoMA in 2004 was manufactured in 1996 and displays an airport’s schedule (Milano, to be exact) on a seven-day loop. The work’s structure consists of a painted metal frame which holds a number of flap units that display a range of alphanumeric silk-screened characters. A flap unit, placed on the interior of the structure, consists of a stepper motor which drives a flap drum and a control system with integrated electronic sensors. These sensors operate based on the Hall effect, a difference in voltage across an electrical conductor that, when applied to a sensor, can be used for proximity sensing, positioning, and speed detection. These flaps are rotated to precision to show the desired character or graphic. The unit is driven by an SBC 3200 controller which is programmed with software that lies in a PC computer running on a Windows 98 operating system. A software application called Message Manager, developed for user input by the Solari Corporation, manages the functioning and performance of the board.

The Split-Flap Board had undergone a series of interventions – moments of study and care – in its past, notably a PHP code hack for displaying custom messages developed by colleagues at the Digital Media Department in 2011 and a comprehensive dusting and cleaning procedure developed by conservator Ellen Moody. Associate Media Conservator Peter Oleksik and Associate Sculpture Conservator Ellen Moody had also taken steps to document cleaning procedures for the delicate silk-screened flaps, as the painted metal is very sensitive to fingerprints and would frequently misalign when handled improperly.

The media conservation team wanted to update the Solari’s communication protocol out of a concern over its reliance on an obsolete operating system, plus the board was expected to be up on exhibition for approximately five years. This raised some concerns about the longevity of the software application which operates and controls a significant aspect of the work. Accordingly, when the Split-Flap Board Flight Information System was scheduled to be installed at the Cullman Education Center at MoMA, the question on our minds was: how stable were the “brains” of the board, if we were to consider a fixed-in-time installation?

With that understanding, I got to work researching a pointedly vulnerable component of the display-board: the single board controller, which is responsible for receiving flight data in the form of a csv (comma separated value) table via Ethernet connection. Taking into account what was on our plate, we started exploring the possibility of reverse engineering Message Manager, the software application utilized, to manage the communication protocol between the control board and user. At this point we determined it was best to consult with Ranjit Bhatnagar, a trusted expert in creative coding and engineering. In coordination with him, we used a Network tap (a device that allows you to tap or “listen” to an ethernet connection) in conjunction with a software disassembler to read and extract the application’s binary code and logic. As a result of this experiment, we were only able to extract “low level” files of the program– these files are written in a programming language that is closer to machine code, and as a result, are of limited use when attempting to reprogram something since there is still a need for human interpretation. It became clear that the reverse engineering pathway would have required too much of an all-encompassing study and research to understand and interpret what is going on “under the hood”. Nevertheless, it was during that process and initial exploration that we were able to extract the csv data tables containing the flight departure information which got us off to a good start.

By way of a spirited connection made through Collection Specialist Paul Galloway, we were able to connect with Amelio Candussio, a Product Specialist at the Solari Corporation, who had worked for the company for decades as a software engineer and thus had an exhaustive knowledge on the inner workings of the Split-Flap board. Candussio had actually been involved in writing the very software that we wanted to upgrade and, much to our surprise, was working out of the Solari headquarters within a stone’s throw of MoMA QNS, the museum’s collection storage facility for conservation, study, and research. With the maintenance of the aging electromechanical components of the device, according to Candussio, each constituent piece of the artwork system represents a vulnerability for the future functionality of the work. “Even if we normally maintain these kinds of boards for 20 or 30 years, there are some cases where some components are no [longer] available.” [2]

With cooperation of our two specialists, Amelio and Ranjit, we moved promptly to coordinate the upgrade. We devised a plan to implement new hardware and upgrade the application software, which necessitated the removal of the aging CPU (Central Processing Unit or the “brains” of the Solari) and replacing it with a contemporary Linux-based CPU. We also installed a new application that relies on wireless connection which would grant a future conservator remote access and troubleshooting capabilities if the board were to fail.

Conservators are colloquially referred to as Art doctors, and in this case, the intervention was the equivalent of an ambulatory surgery. The rehabilitation of components took a couple of days and after hours of testing, the Solari was now functioning properly. After installing the Solari board, we transitioned to documenting the upgrade and summarizing what we learned from the old communication protocol in conjunction with our consultants, and kept all of the removed components. An essential tenet of conservation treatment is reversibility; we ensure this by writing up treatment reports, which recount and evaluate an intervention. Our reporting for this treatment also included an operation manual for navigating the new software application and was informed by a newfound understanding of the characteristics – both old and new – of the split-flap board. In his 1997 book, War and Peace in the Global Village, philosopher Marshall McLuhan hypothesized that “All new technologies bring on the cultural blues, just as the old ones evoke phantom pain after they have disappeared.” By enacting this conservation treatment, we made a conscious effort to maintain the ability of the Solari in encompassing both the cultural blues of an epoch of travel, migration, and so-called upward mobility, and the contemporary phantom pain from the convalescence of a raucous journey through modernity and onward.

[1] “Fluttering Code: A Cultural and Aesthetic History of the Split-Flap Display,” Shannon Mattern, Modes of Criticism 5 (2020): 49-63

[2] “Fluttering Code: A Cultural and Aesthetic History of the Split-Flap Display,” Shannon Mattern, Modes of Criticism 5 (2020): 49-63