This week’s contributing writer, Hannah Sage Kay, is currently undertaking graduate study in modern and contemporary art at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Her research focuses on the intersection of art and politics with regard to media manipulation, misinformation, and the construction of fictionalized (or alternate) histories.

A pseudo-documentary comprising found footage, staged interviews, and an AI generated script, Don Edler’s Devil You Know (2020)—which streamed exclusively at Hunter Shaw Fine Art in Los Angeles between January 10 and February 7, 2021—presents a disquieting foray into the minds and algorithms that polarize online discourse, contemporary politics, and popular belief systems.

Mainstream media coverage of the information crisis in the United States cannot prepare viewers for the deluge of conflicting biases, “facts,” and modes of presentation comprising Edler’s feature-length video, in which authorship and facticity are nearly impossible to discern.

Presenting neither a cohesive narrative nor a consistent political perspective, Devil You Know quickly overwhelms viewers by distorting oft relied upon visual and verbal signifiers of veracity—what the exhibition’s press release has termed the “aesthetics of credibility” and the “credibility of aesthetics.” Trying to find a common thread or shared ideology throughout the video’s numerous segments—on capitalism, QAnon, Russian troll farms, the anti-vaxxer movement, Black Lives Matter protests, and 5G technology—is not only a futile effort, but a missed point. Devil You Know does not convey any strictly sorted belief system, since so much of the information presented transgresses accepted parameters of liberal and conservative, Democrat and Republican. Rather, it reflects the cacophony of voices shouting into a virtual, and increasingly omnipresent void: the internet. Edler thus effectively holds a mirror up to our present informational ecosystem, creating a veritable portrait of online discourses and personalities.

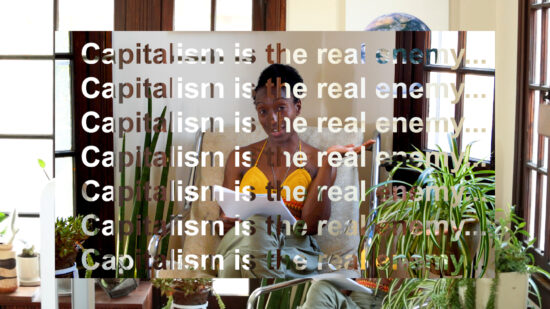

Don Edler, Devil You Know, 2020, feature-length video. Courtesy of Don Edler and Hunter Shaw Fine Art.

Devil You Know begins and ends with the same statement: “Capitalism is the real enemy. It’s the monster that goes bump in the night. It lurks and it hungers for human blood and human bodies[…] Capitalism is killing this planet and the human race[…] Capitalism has shown America the way to allow people to starve to death. The devil you know, the better it is. The devil you don’t, the worse it is.” Oscillating somewhere between the condemnatory and the poetic, these rather nonsensical lines somehow make sense in that one wouldn’t expect a poem titled “Capitalism”—performed by a millennial YouTube influencer and poet with a valley-girl accent—to be anything but a regurgitation of pop liberal phrases and watered-down faux-anarchic ideology. The coherence of these same lines dissolves somewhat while, paradoxically, their plausibility grows when read without poetic inflection by another character at the end of the video. A bespectacled academic in a tweed jacket, who moments prior concluded a rant about socio-capitalism, bestows by way of his affect and attire an air of believable authority to the recitation of gibberish.

In the instances of both the influencer poet and the bespectacled academic, presentation compensates for the occasional incoherence of Edler’s script, which was written in collaboration with OpenAI’s deep learning-based language model, GPT-3. Known for its ability to generate text nearly indistinguishable from that of humans, Edler fed the AI samples of his own writing on various topics, in multiple prosaic styles, and with contrasting political inflections, prompting it to fashion an entirely new body of text. After selecting segments from the nearly 40,000-word document created by GPT-3, Edler hired two actors—Nikelola Balogun (the poet) and Joel Pelletier (the academic)—to read portions of the text. Natural sounding, though clearly artificial, voices offered by the Amazon Polly text-to-speech service narrate the remainder of the script. Differences in cadence, as well as those of the race, class, gender, and personality of the performers and narrators, ultimately shape the reception of Devil You Know—drawing out viewers’ inherent biases regarding who and what they are willing to believe.

Don Edler, Devil You Know, 2020, feature-length video. Courtesy of Don Edler and Hunter Shaw Fine Art.

The nature of bias, equity, and objectivity are similarly explored in Theo Anthony’s recently released film, All Light, Everywhere (2021), with regard to government-sanctioned surveillance technologies. Most notably, however, his film shares certain narrative and filmic techniques in common with Devil You Know—specifically, a performative transparency regarding the makers and making of the work itself. By widening camera angles to include those behind the camera—and theoretically acknowledging the power dynamic at play, between director and performer, camera and subject, viewer and viewed—Edler, like Anthony, simultaneously illuminates and implicates himself. Edler’s role, identity, and agenda become foregrounded in that which he’s created, causing one to wonder to what extent “transparency” begets trust.

While the early 2000s saw a proliferation of what art historian Carrie Lambert-Beatty has termed “parafictional art”—work that presents and disseminates fictions as facts[1]—our post-truth era has witnessed a decrease in these very practices that foreshadowed it, while politically and informationally charged work has become ever more literal. Literal in that the subjects at hand are presented without obfuscation or ambiguity, taking on a sort of explanatory or diagnostic format.[2] This modality can be exemplified by the work of Trevor Paglen or Cameron Rowland, as well as that of two other recent exhibitions at Hunter Shaw Fine Art: Colleen Hargaden’s Strategies for Inhabiting a Damaged Planet and the group show Reality is Canceled, of which Edler was also a part. Such work remains distinct from parafictional art in that it leaves no mystery as to its true subject and tactics, confronting issues head on. Edler’s video work adopts this format by way of its pseudo-documentary status and explicit contextualization in the press release. It cites work by other artists that engages with similar themes, such as Bill Poster’s (a.k.a Barnaby Francis’) deepfake video of Kim Kardashian, When there’s so many haters… (2019); Stephanie Lepp’s deepfake video of Mark Zuckerberg from her Deep Reckonings series; and CGI avatar and influencer Lil Miquela—created and puppeteered by Brud, a Los Angeles-based AI and robotics startup.

Don Edler, Devil You Know, 2020, feature-length video. Courtesy of Don Edler and Hunter Shaw Fine Art.

Not at all surprisingly, a 2018 article in The Cut observed that “social-media personalities like the Kardashians alter their bodies and edit images of themselves so heavily that CGI characters [like Lil Miquela] somehow blend naturally into our feeds.”[3] Our desire, perhaps more so than our ability, to distinguish fact from fiction has massively degraded. We love virtual companions,[4] we follow virtual influencers,[5] and we worship virtual gods.[6] The latter, exemplified by Q of QAnon, has proven most concerning, as it simultaneously encourages blind belief in an un-named and un-vetted source, suspends the need for verifiable evidence or facticity, and triggers behavior consistent with pareidolia.

Pareidolia, as a male Amazon Polly narrator explains in Devil You Know, contributes to our predilection to see shapes in clouds and logic in conspiracy theories. However, Polly doesn’t postulate that pareidolia bears much in common with the practice of art viewing. Art audiences have historically been encouraged to make connections, identify symbols, and find evidence for variously plausible stories within visual material and culture. Within the context of the field, such practices are in no way unusual or unorthodox, prompting one to wonder, as Nelson Goodman does in his canonical essay “When is Art?,”[7] precisely that: when, not what. In which contexts and circumstances can real-world strategies and symbols be received (under the functionally neutralizing guise of art) not as the thing itself, but as “an example” or “sample” of it? In which scenarios are deepfake videos and AI generated texts not instruments of misinformation and manipulation but critically illuminating exemplars of it that prompt us to think deeply and differently about that which we encounter every day? Devil You Know serves as one such example, drawing viewers into the fictive so as to better diagnose the real.

[1] Carrie Lambert-Beatty, “Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,” October Magazine, Ltd. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology 129 (Summer 2009).

[2] The allusion here to Michael Fried’s “literalism” is a welcome one since he criticized in Art and Objecthood the breakdown between art and life, the real and the illusory. In arguing that these categories should remain separate, he disparaged Minimalism’s encroachment on “the real.” It follows that artwork of an explanatory or diagnostic nature—which openly takes on the same form and tactics as the subject it addresses—would be, by his definition, overly literal.

[3] Emilia Petrarca, “Lil Miquela’s Body Con Job,” The Cut, May 11, 2018, https://www.thecut.com/2018/05/lil-miquela-digital-avatar-instagram-influencer.html.

[4] Chen Du, “Microsoft’s Chinese Spin-off Wants Everyone to Have a Virtual Companion Like Samantha in ‘Her,’” PingWest, August 21, 2020, https://en.pingwest.com/a/7555.

[5] Haneesa Begum, “Instagram Influencer, Singer and Model – and Computer Generated: Rise of the Virtual Kings and Queens of Social Media,” South China Morning Post, July 8, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/arts-culture/article/3091979/instagram-influencer-singer-and-model-and-computer-generated.

[6] Adrienne LaFrance, “The Prophecies of Q: American Conspiracy Theories Are Entering a Dangerous New Phase.,” The Atlantic, May 24, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/06/qanon-nothing-can-stop-what-is-coming/610567/.

[7] Nelson Goodman, “When Is Art?,” in Ways of Worldmaking (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 1978).