This week’s contributing authors are undergraduate students Sarah Abeywardena and Ashlynn Braisted, both pursuing a BS in Computer Science and Design, Caeli Jackson, pursuing a BSBioE in Bioengineering and Biochemistry, and Jessica Xing, pursuing a BFA in Design, at Northeastern University.

VoCA is pleased to present this blog post in conjunction with Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History, Gloria Sutton’s Spring 2022 Honors Seminar, The Art of Visual Intelligence at Northeastern University. This interdisciplinary course combines the powers of observation (formal description, visual data) with techniques of interpretation to sharpen perceptual awareness allowing students to develop compelling analysis of visual phenomena.

Located in Emerson College’s contemporary art platform, Emerson Contemporary, Boston-raised artist Kerry Tribe’s “Onomatopoeia” depicts the complexities of language and communication in a variety of mediums from video projections to silkscreen prints and audio recordings. Tribe worked with Leonie Bradbury of Emerson College’s Media Art Gallery to curate this exhibit with its location, and specifically Emerson’s Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, in mind. “Onomatopoeia” demonstrates the artist’s interest in topics surrounding cognizance and recollection, broadening her previous work discussed in the VoCA Blog article “Documentary Adjacent.” The exhibit debuts Tribe’s newest work, Corner Piece (2022), her most personal work in the exhibition. Corner Piece takes snippets of conversation from Tribes own day to day life, highlighting the challenges and differences of communication between family members and through generations. We had the pleasure of communicating with Kerry Tribe and together curated a Q&A in which we discussed her intentions behind her design decisions in each piece, how her work affects the communities she represents, and the challenges she faced when creating work outside of her native language.

What were some considerations for your exhibition Onomatopoeia, which was on view January 26 to March 27, 2022?

Tribe: The works in Onomatopoeia are intended to encourage metacognition and awareness of the privilege that comes with fluency. Some works in the exhibition, such as Afasia (2007) and The Last Soviet (2010) rely on complex relationships among written and spoken words in more than one language and are uniquely challenging to viewers with cognitive disabilities. I consulted acquaintances with different forms of aphasia while making the work and trust that it “lands” in meaningful ways for audiences of diverse backgrounds and abilities. But from the get-go, I was primarily thinking about Emerson College, a “school of oratory” as a context for this exhibition. Known for its programs in film, media arts, and journalism, the small liberal arts college also houses a Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders. From our first meeting, Leonie and I agreed we wanted to put together a show focused on communication. And because Boston is my hometown, we wanted to include some more personal works, like Afasia and Fantastic Voyage (2020). Corner Piece (2022), the most autobiographical work in the show, came together as the exhibition developed.

Several of your artworks center on Aphasia, a neurological condition in which the brain has difficulty processing language. Why might photography and video —inherently visual mediums— be effective tools for understanding a neurological sense of linguistic disconnection?

Tribe: This is a complicated question. I actually wouldn’t argue that these mediums are especially useful tools for understanding the aphasic experience. I do, however, find them effective tools for engendering empathy in art audiences. Your word choice points to a subtle and compelling question: “understanding” suggests rationality while “sense” suggests emotion. What does it take to “understand a neurological sense” other than our own? Clinically speaking, effective empathy demands the ability of one person to take the perspective of another both cognitively and emotionally. Understanding without affect tends to beget disengaged analysis. Feeling without the critical distance that cognitive analysis affords tends to produce pity. Compassion in action requires both thinking and feeling. This is precisely the dialectic that interests me. The complex play of identification and distancing that experimental documentary affords would seem to offer a step in the right direction.

Kerry Tribe, The Last Soviet, 2010

Single channel video with sound, duration: 10:44

Courtesy of Emerson Contemporary Media Art Gallery

In many of your time-based media works you switch between spoken language and written captions when addressing the viewer. How do these techniques foreground the conceptual relationship between language and media, specifically ideas around fluency, synchronization and their inverses, breakdown and failure?

Tribe: We’re all fluent in the language of mass media whether we’re conscious of it or not. My use of multiple languages, captions that serve as translation, presenting the voices of people we never see and seeing people we never hear—all these approaches are designed to suggest the feeling of being lost in language. I speak a little Spanish, and almost no Russian. I can’t understand half the words in The Last Soviet, and I probably mispronounce half the words in Afasia.

Kerry Tribe, Prueba de colores y palabras, 2017

Silkscreen on paper, 36” x 27” each

Courtesy of Emerson Contemporary Media Art Gallery

How does your work facilitate meaning and understanding by putting your audience in positions or situations that exceed their familiarity or own knowledge?

Tribe: A number of the works in Onomatopoeia use cognitive dissonance as a way to encourage viewers to pay attention to the experience of paying attention. The silk-screened posters Pruebas de colores y palabras (2017), for example, illustrate the Stroop effect: the delay in reaction time when subjects encounter incongruent stimuli—in this case words referring to one color printed in a different color. This “color-word interference test” is frequently used in clinical assessments for learning and attentional differences. It’s a point of departure for the silkscreens, whose tenor is decidedly friendlier, even goofier than it is clinical or scientific. Presenting the work in Spanish–one of Boston’s non-dominant languages—connects the project to Afasia, in which I describe, in faltering Spanish, my effort to improve my Spanish. Where your standard documentary narration would speak with authority, my voiceover, more characteristic of my approach in general, meanders through a series of questions, digressions and apologies.

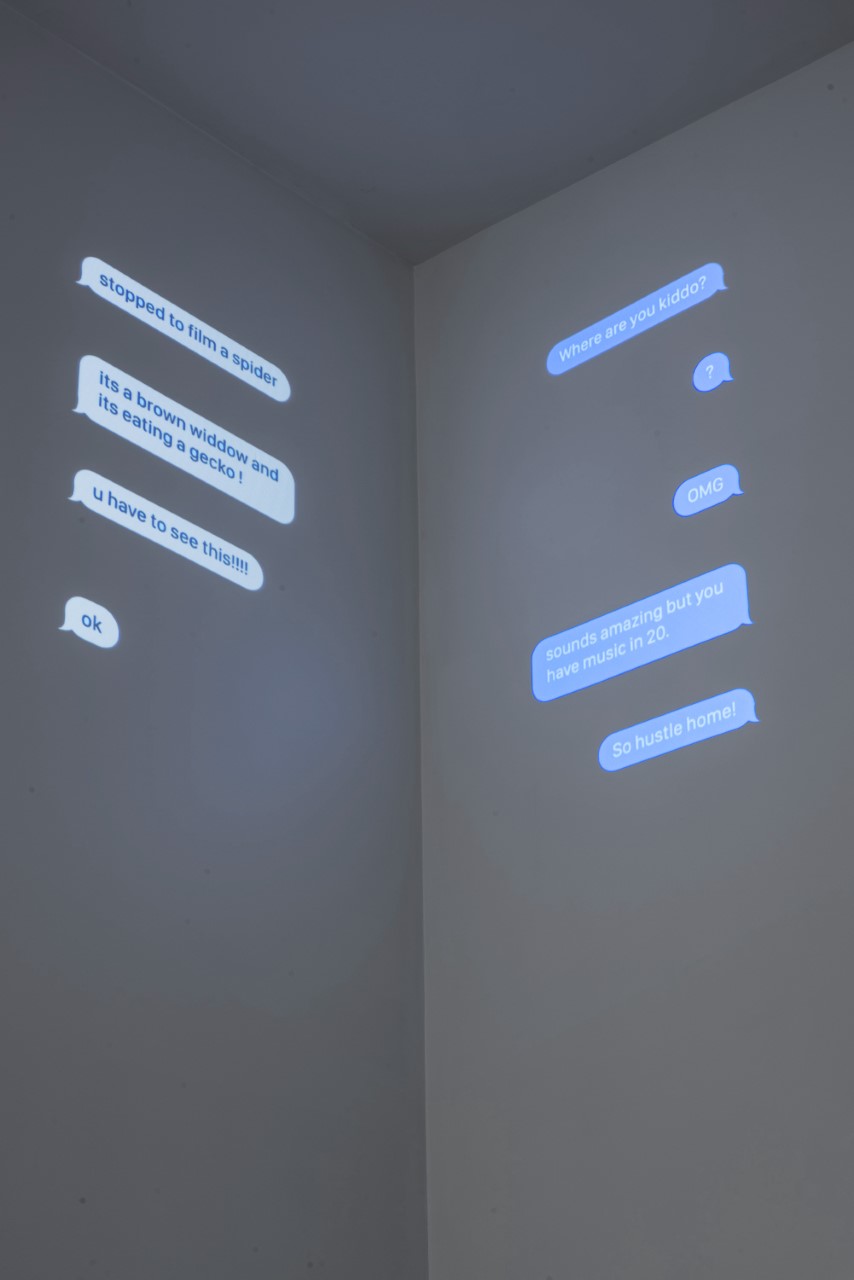

Kerry Tribe, Corner Piece, 2022

Video projection with sound, duration: 24:20

Courtesy of Emerson Contemporary Media Art Gallery

Your most recent work, Corner Piece takes the form of iMessage exchanges between family members—how does the piece extend your investigations into personal speech acting as public?

I was thinking about how dependent I’ve become on these ubiquitous communication technologies in my effort to take care of the people for whom I’m responsible. As the mother of two school-aged boys who recently emerged from the traumas of Zoom school only to enter the traumas of in-person school, and as the grown child of an elderly and infirm mother who lives across the country (in Boston, no less), the text exchanges in Corner Piece have me ping-ponging across a corner of the room and a generational divide in my daily effort to keep the wheels from coming off the bus. People keep telling me they find Corner Piece “relatable,” a term I actually had to look up the first time I heard it, because it seems to confuse an indirect object for a subject. This, as you might imagine, I think is just marvelous.

What are some considerations around accessibility and mobility in making an audio recording as a work of art, specifically Fantastic Voyage (2020) which was commissioned by the Orange County Museum of Art with funding provided in part by the National Arts and Disability Center at the University of California Los Angeles and Ability Central California, Los Angeles?

Tribe: Fantastic Voyage was one of a series of audio projects OCMA commissioned for Soundcloud when the pandemic forced museum programming to go virtual. As I understand it, these projects were supported in part by grants OCMA received to optimize their programming for the visually impaired. So-called “walking meditation” is easily modified for people with limited mobility, but until I sought the involvement of an advocate for the visually impaired, it hadn’t occurred to me that, for example, walking outside with headphones might be dangerous if you count on your hearing to make sense of your surroundings. (Duh!)

How do you think it syncs up with the themes you examine visually within Onomatopoeia?

During the pandemic my family, like so many families, found ourselves isolated and stir crazy stuck in our home, at once together and alone. Taking walks around our neighborhood became for us a means of re-connecting with our bodies and one another, as well as with the larger world, in a time of environmental and social uncertainty. The soundtrack is punctuated by snippets of recordings made with my kids and husband at home. So, while it’s ostensibly a “guided walk,” it’s more fundamentally a guided exploration into how it feels to be aware of our own subjectivity, moment to moment, in whatever form this embodied life offers up.

Onomatopoeia offers unique perspectives on communication and language in a manner which addresses issues faced by various groups in her community. Presenting works in Boston’s non-dominant languages, as well as including a piece that is entirely audio-based, aims to engender empathy from her audience by experiencing what it is like to face various communication limitations. While each piece focuses on a specific limitation, the works come together to generate a cohesive message on metacognition and privilege in interaction.