This week’s contributing author, Stella Westlake, is a third-year undergraduate student at Northeastern University pursuing a combined BA in Journalism and Art History with a minor in Global Fashion Studies.

VoCA is pleased to present this blog post in conjunction with Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History, Gloria Sutton’s Fall 2020 Art History Course: Disruptive Image Technologies at Northeastern University. This interdisciplinary course examines how the distribution, circulation, storage and retrieval of still and moving images have shaped the understanding of contemporary art.

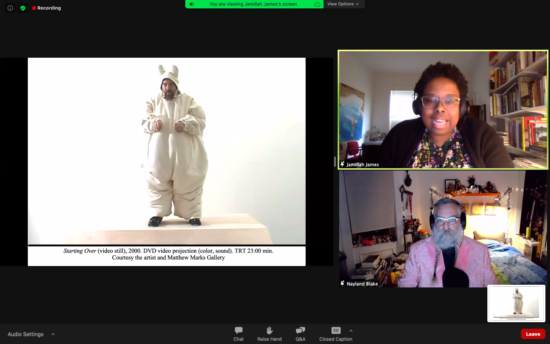

In artist Nayland Blake’s 2000 video performance Starting Over, Blake, nearing 6 foot tall and sporting the beginnings of what is now a long, wizard-like beard, wears a rabbit costume filled with 147 lbs of navy beans—equivalent to the weight of their partner at the time, the late choreographer Phillip Horovitz. In wearing the suit, Blake takes on the role of the innocent and mischievous bunny as well as the literal and emotional weight of their relationship. From beyond the camera, Blake’s partner gives them instructions to dance through progressive exhaustion until they ultimately collapse.

Starting Over, a clip of which was played for attendees of a virtual event hosted by the MIT List Visual Arts Center on October 26, 2020, is a comedic yet disturbing view into the challenges of relationships that exposes the fine line between nurture and love—symbolized by the soft bunny imagery and a helpful reading of the instructions—and abuse and control—embodied in the relentless commands continuing through visible fatigue leading to emotional bankruptcy. Blake often uses such contrasting elements of flowers, bunnies, fairy tales, children’s stories, and bondage, leather, and steel as tools to tell their story as a queer, bi-racial, non-binary artist. This exploration of duality is prominent throughout Blake’s body of work, which, according to List Center Assistant Curator Selby Nimrod, began in the 1980s against a backdrop of the HIV/AIDS epidemic continuing through the first “culture wars” of the 1990s into our present age.

Nayland Blake and Jamillah James play a 30-second clip of Starting Over using Zoom’s share-screen function.

Starting Over and the recurring themes surrounding identity within Blake’s work are as relevant today as they were 20 or 30 years ago. Their recent 30-year career retrospective exhibition, “No Wrong Holes,” curated first for the Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles by Jamillah James, and then for the List Center by Nimrod, cast Blake’s investigation of duality in a new light for a present-day audience—one born into the society of increased acceptance artists like Blake fought to create. Although the List Center closed their doors to visitors on March 13th, 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, they nonetheless chose to physically install the exhibition in their gallery, a testament to the critical importance of Blake’s work. Unable to provide would-be visitors with the meandering and rumination that usually take place in the white cube gallery space, the List Center offered instead a deep dive into the exhibition in the form of a conversation between Blake and James from the (paradoxically) intimate pixelated cubes of the pandemic-responsible public gathering space: Zoom.

The bunny, along with use of toys and child-like imagery, is a recurring trope in Blake’s work, and was derived from Blake’s childhood obsessions with Looney Tunes and a certain anthropomorphized carrot-eating rabbit, Bugs Bunny. It appears in drawings, sculptures, and costumes for video and performance pieces as an avatar—or surrogate—for soft forms and childhood. As children we often project invented personalities and imagined agency onto the inanimate objects we play with; the bunny appears as a representation of the cultural agreement of the prescribed subjecthood given to the insentient in youth. However, the bunny can also be read as reflecting another facet of Blake’s identity by drawing a parallel between the stereotyped promiscuity of the gay community and the idea of “fucking like rabbits”. “One of the things that is a through line in all of the work that I have made is that I’m very interested in looking at things I encounter in everyday life and asking what happens when I change the context of them,” said Blake during their conversation with James.

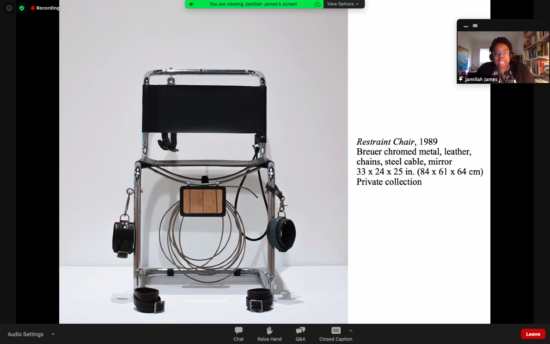

Nothing is more representative of this idea than Blake’s 1989 object sculpture, Restraint Chair: a sleek black and silver Marcel Breuer s34 knockoff design equipped with steel shackles and leather cuffs, primed to hold someone down in what could be seen as a sexual context. An image of the discomfiting work was broadcast to attendees during the virtual event, but the erotic reading of the image turned quickly to evil within just a few seconds of dialogue. As a black person, Blake noted, what did their continued use of chains and restraint equipment, which evoke a particular association with slavery and human bondage, mean for their understanding of their own sexual proclivities and enjoyment and where did they come from?

Images of Nayland Blake’s sculpture Restraint Chair installed in the List Center, shown to attendees during the October 2020 virtual event hosted by the List.

“Where does a potential interest in being reduced to a piece of furniture come from and what are the historical and racial valances for that?” they said. “I do believe that one of the things we do with sexuality is to process trauma. That it is not the same thing as therapy but that it is a way of enunciating our traumas and fears and articulating them bringing them into the world and then through working with them working through them.” Even without the added context of Blake’s identity, the piece’s cold, industrial construction evokes a sinisterness beneath its overt sexuality that briefly takes your mind to a more horrific arena, perhaps the squeamish quiet of a horror movie approaching its painful climax. Restraint Chair again furthers ideas of surface ambiguity and bodily surrogacy that actively conceal the true self and hide “what might lurk behind underneath the surface.”

By presenting “No Wrong Holes,” and the accompanying dialogue with Blake, the List Center allowed Blake’s ideas to take up the space they require and deserve, in both a physical sense and a higher cultural one. In 2020, complex identities that stray from the societally conceived “standard”, and the idea that every body is okay and allowed to be, has become increasingly normalized. For many millennials and generation Z, it is all they know. “No Wrong Holes” gives voice to the long history of struggle it took to reach this point, ensuring it isn’t forgotten.