This week’s contributing writer, Nikhil Phatak, is a fourth year undergraduate student at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts pursuing a combined BS in Computer Engineering and Computer Science.

VoCA is pleased to present this blog post in conjunction with Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History, Gloria Sutton’s Spring 2020 Honors Seminar, The Art of Visual Intelligence at Northeastern University. This interdisciplinary course combines the powers of observation (formal description, visual data) with techniques of interpretation to sharpen perceptual awareness allowing students to develop compelling analysis of visual phenomena.

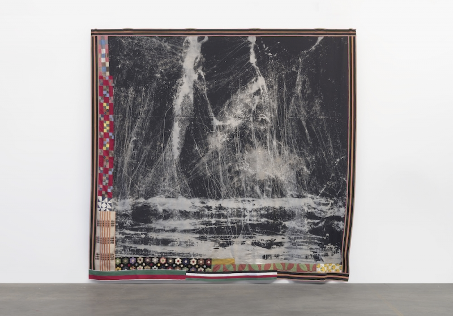

When viewing the first comprehensive museum survey of American artist Sterling Ruby at the Institute of Contemporary Art, the monumentally-scaled textile work, FLAG/QUILT (6625) (2018), grabbed my attention. The work incorporates fragments of both non-Western and Amish weaving styles and patterns foregrounding the ways Ruby both relies on and transforms traditional quilting techniques within contemporary art. More broadly, the exhibition curated by Barbara Lee Chief Curator, Eva Respini, highlights how everyday items like clothing, furniture, and tools used in North America and Europe are often taken for granted. Since the turn of the 20th Century, Western economies have transitioned from being manufacturing-dominated to being service-focused. As a result, large-scale manufacturing has moved to countries where labor is cheaper and products can be mass-produced using lower-quality materials. In the wake of this shift, there has been a drastic influx of “artisan” products: items made by hand using high-quality, non-synthetic materials such as bamboo, wood, metal and textiles. This ethos has also entered the world of contemporary art, where handcrafted, stylized everyday items such as Ruby’s quilts are prized and valued while the people who actually create these objects for their everyday use remain unacknowledged and invisible.

This chasm in reception and recognition prompted me to consult Design Historian Dr. Ezra Shales whose scholarly book, The Shape of Craft (Reaktion Books, 2017) aims to upend the simplistic categories of “fine art” and “craft,” explicating the differences between contemporary artists engaging in craft work and ordinary craftspeople using their artisanal skills as their profession. Below is a condensation of my recent conversation with Shales who is Professor of History of Art at Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

Nikhil Phatak: Why is there such a great divide (in terms of monetary value and recognition) between textiles, particularly quilts and rugs, produced by laypeople who create textiles for their livelihoods and contemporary artists (such as Sterling Ruby) who create and have gained prominence for their textile productions, when the end products may be very materially and visually similar?

Ezra Shales: Cultural institutions will always attend distinctly –and unevenly—to the merits of a quilt made for a bed and a canvas stretched on the wall as ‘art.’ Art vindicates the very idea of the ‘fine art’ museum. The annual graduation of MFA-trained artists is groomed to provide product for white walls and even when wonderful artifacts such as the quilts of Gee’s Bend are picked up and recognized as ‘art’, and hung vertically and no longer as bedding, the great majority of textiles that are made outside of the MFA-universe will not be read as intellectually, emotionally or psychologically rich as pre-approved ‘art.’ We must take umbrage in the fact that the art market is unregulated and that work like Gee’s Bend does pop up and dislodge the status quo. I also take solace when artists like Mike Kelley disrupt these value systems (More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid (1987)) or when artists credit and list collaborators extensively.

NP: You talk about basket making—specifically the “bamboo chairs and rattan wastepaper baskets and the Indonesian and Vietnamese laborers who weave them in sub-par conditions” for people to buy cheaply from IKEA, noting that “valuing both the basket and the basket-maker combines appreciation for both human frailty and genius.”[i] How do the class differences between unnamed artisans and well-known contemporary artists play into the recognition and reception of contemporary art that appropriates traditional craft?

ES: “Without slavery you have no cotton; without cotton you have no modern industry,” wrote Karl Marx, and I would be hard-pressed to argue with this generalization if applied to the larger dynamic of Western consumption today. How do class differences not play out? The art world is a microcosm of the broader power dynamics that undergird our social and economic systems and there is a limit to the critical language used to illuminate these inequalities. The term “appropriates” for example, merely signals a sense of moral disapproval yet in the current moment remains inadequate.

Sterling Ruby, FLAG/QUILT (6625), 2018. Bleached denim, treated fabric, and elastic; 164 × 170 inches. Image courtesy of Sterling Ruby Studio, Los Angeles. Photo by Robert Wedemeyer.

Most labor that produced 99% of the artifacts in museums was not free and not compensated. We can’t only speak of “cultural appropriation” as a phenomenon occurring between the developed world and “emerging economies,” and we must think of neocolonialism as having a long history. Some really smart exhibitions, such as Grayson Perry’s “Tomb of the Unknown Craftsmen” (2011) at the British Museum and Daniel Charney’s “Power of Making” (2011-12) at the V&A attempted to cross these lines in generative ways.

NP: Various communities often produce artisan crafts for themselves while also producing a separate subset of their wares for export/distribution. What effect does this have on public perception of their craft and appropriation of their craft in the contemporary art world?

ES: Public perception is a slippery thing, but holding museums and cultural institutions accountable as to how they exhibit and collect the work of artisans laboring in informal economies is a moral aim that I wish was more widespread. Touristic commodification has a long history. For instance, the policing of what constitutes “Indian Art” within Native American communities has been problematic, both in terms of pressure exerted upon native communities and within those communities, too. Recent profiles of artists such as Oscar Howe or Jaune Quick-to-See Smith articulate these issues. I have recently been writing an essay on a designer who has worked for IKEA for twenty years and who is Swedish-Sámi and some say she has exploited her Sámi heritage for IKEA’s benefit. This is a new chapter of an older story but the ethical terrain is more complex than ever before, as numerous Sámi can be found commodifying historic traditions in craft. These issues ripple into the contemporary art world, too; it is not some bastion of purity or ethical practices. While it’s not Ruby’s intention, his work at the ICA does foreground the tensions between craft and fine art –but so does the work of Rachel Harrison, one could argue. Whether there is value in contemporary art institutions such as the ICA elevating fiber and ceramics or if the next ‘crafty’ materials will be the once-tired-now-exciting media of bronze and marble, once again, is anyone’s guess. Few of us would expect to find ‘Native American art’ or ‘African art’ on display in the Museum of Modern Art today, but they were there in the 1930s and 1940s.

Mary Lee Bendolph, Work-clothes quilt, c. 2002. Denim and cotton; 99 1/2 x 88 in. Image courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Shales’s insights point to the uneven reception between artists and artisans within contemporary art. Ruby’s prominence stands in stark contrast to the relative namelessness of actual working-class people who take part in these crafts not for their own comfortable livelihood, but for the utility of their creations. One of the residual effects of Ruby’s first museum survey is how Ruby’s visibility represents a cultural about-face, from a love for the uniformity of mass-produced goods to a reverence for the imperfections and irregularity of that which is made by hand rather than by machine.

[i] Ezra Shales, The Shape of Craft (Reaktion Books, 2017), p.23