This week’s contributing writer, Jonathan D. Katz, is an activist academic who was the first American be tenured in what was then called Lesbian and Gay Studies and chaired the first such department in the US, and subsequently the first in the Ivy League. A pioneering scholar working at the intersection of art and sexuality, he curated the award-winning Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, the first queer art exhibition ever mounted at a major US museum, Art AIDS America, and numerous other queer art exhibitions.

In the face of several excellent historical Stonewall 50th anniversary exhibitions, I had permission to try something different. What if we sought to re-animate the emotions of Stonewall with new art works, in an exhibition that groped, the way Stonewall had groped, towards a more equitable future without knowing in advance what that world would look or feel like? The result is About Face: Stonewall, Revolt and New Queer Art, now open at Wrightwood 659, an exhibition space in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago, through an extended run closing August 10, 2019. At 494 works, it’s not only the largest queer exhibition ever mounted anywhere, but among the most diverse, with a fully international roster of artists, many of whom are either women or gender queer. By design it offers what are effectively mini-retrospectives of the work of a number of artists, some of whom have never been shown in a museum exhibition before, or are being shown in a US museum for the first time.

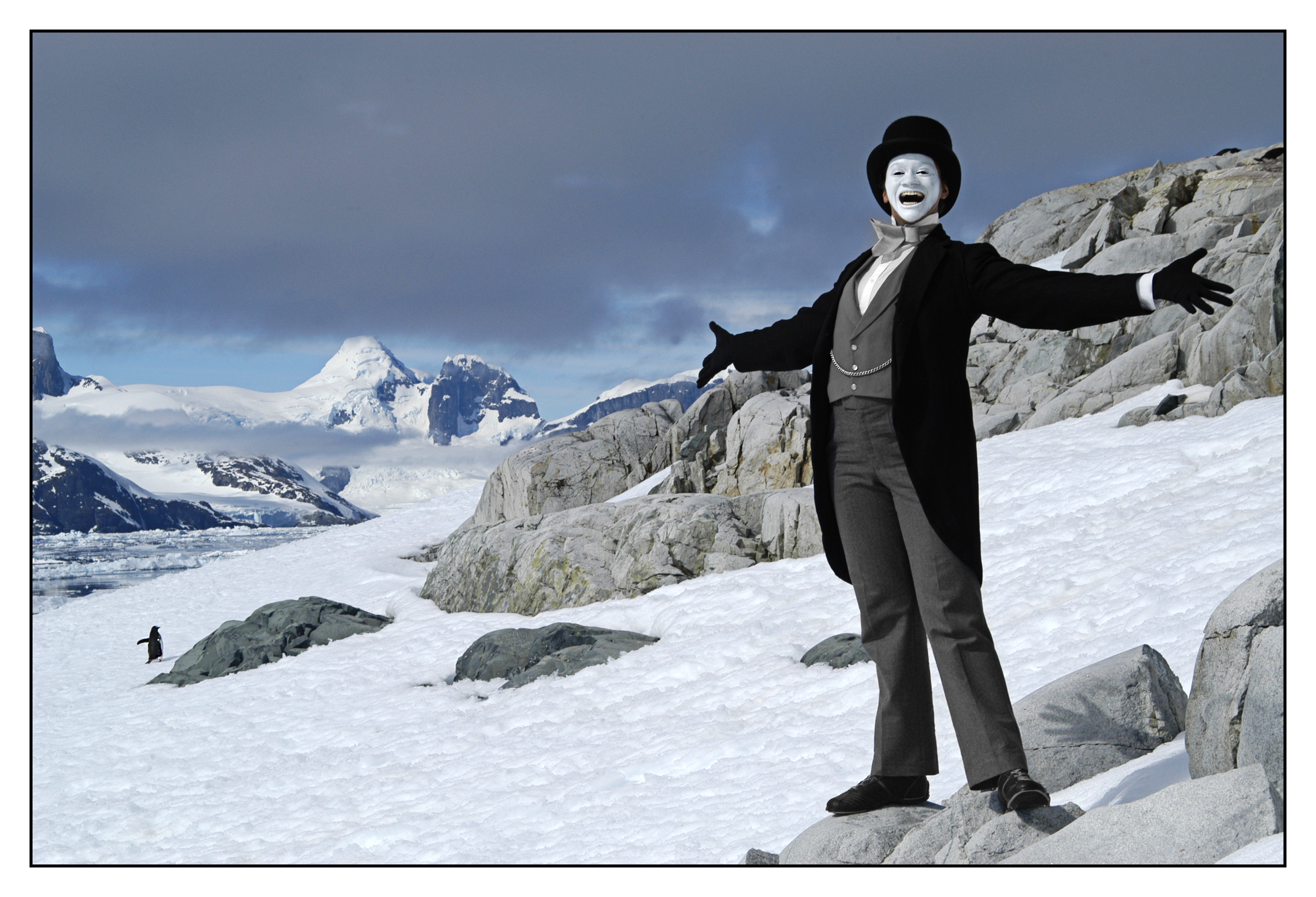

Representing works from 14 countries, the exhibition deliberately presents under-represented artists whose works rival in quality the best art being done anywhere, but who may have been marginalized by their choice of subject matter, or because they died in the AIDS epidemic before their careers took off, or who had no access to the art market or museum world. In other instances, the names are well known, but the art is not. For example, Harvey Milk, the queer politician murdered in San Francisco, is represented by a strikingly accomplished collection of never before seen photos found among his papers, some of which date back to 1952. Arguably Canada’s leading artist, Kent Monkman, here shows what many consider his masterwork, Dance to the Berdashe, never before exhibited in the US. The artist is part Cree, and the work features indigenous dancers doing traditional dances projected onto buffalo hides. But these dancers incorporate bits of hip hop, or Hollywood routines, and the music shifts to include everything from hip hop to jazz, as the viewer realizes that the “buffalo hides” are in fact machined artifacts referencing European lace. Soon, the viewer catches on to Monkman’s view of the world, that there is no “my” culture and “your” culture, that we’re always already hybrids, that culture is always a shared experience.

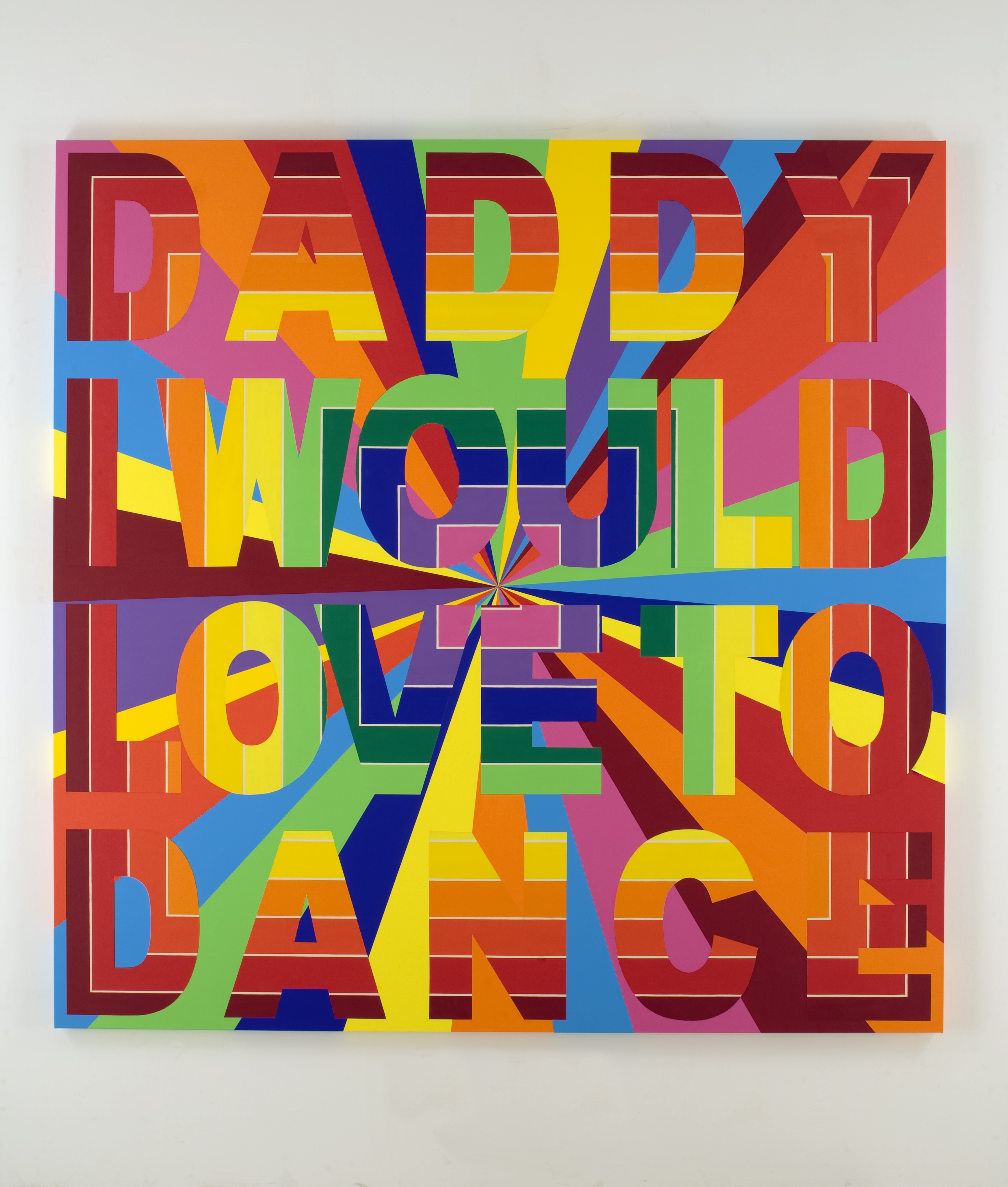

The selection of magisterial photographic self-portraits by the rising South African international art star Zanele Muholi exceeds the number on view this year in the Venice Biennale, the largest international group exhibition. This series of works takes the viewer’s fascination with an African “otherness,” and re-presents it for a mainstream art world audience in ways at once shocking, gorgeous, enticing and sad—but always aesthetically alluring. The series, completed just this year, is already being addressed as among the greatest photographic portraits ever made. By contrast, Deborah Kass’s large, vibrant paintings promiscuously quote queer musical theater and popular culture in the context of queering some of the most blue-chip contemporary American artists such as Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, or Frank Stella. Bringing the low high and the high low, here is a self-declared lesbian feminist artist trafficking in stereotypical gay male culture and having a blast doing so.

Amos Badertscher’s photographs are being shown publicly for the very first time. Over the last 60 years, the artist, now in his 80s, has been taking extraordinary images of young male hustlers in ways that reinvent the iconography of the male body in a gay key. I chose about 80 from a selection of many thousands of photographs stacked in boxes in his Baltimore apartment, unseen. The images chronicle a particular Baltimore subculture in which largely heterosexual working-class youth hustle, as did their fathers before them, in order to support their drug addictions. Despite the often depressing subject matter, and the sad fact that many of the youths are now dead—noted by the artist in a biographical overview scrawled around the image—the images are among the most popular in the exhibition for their formal daring and beauty, all the more remarkable as the photographer was never formally trained as an artist.

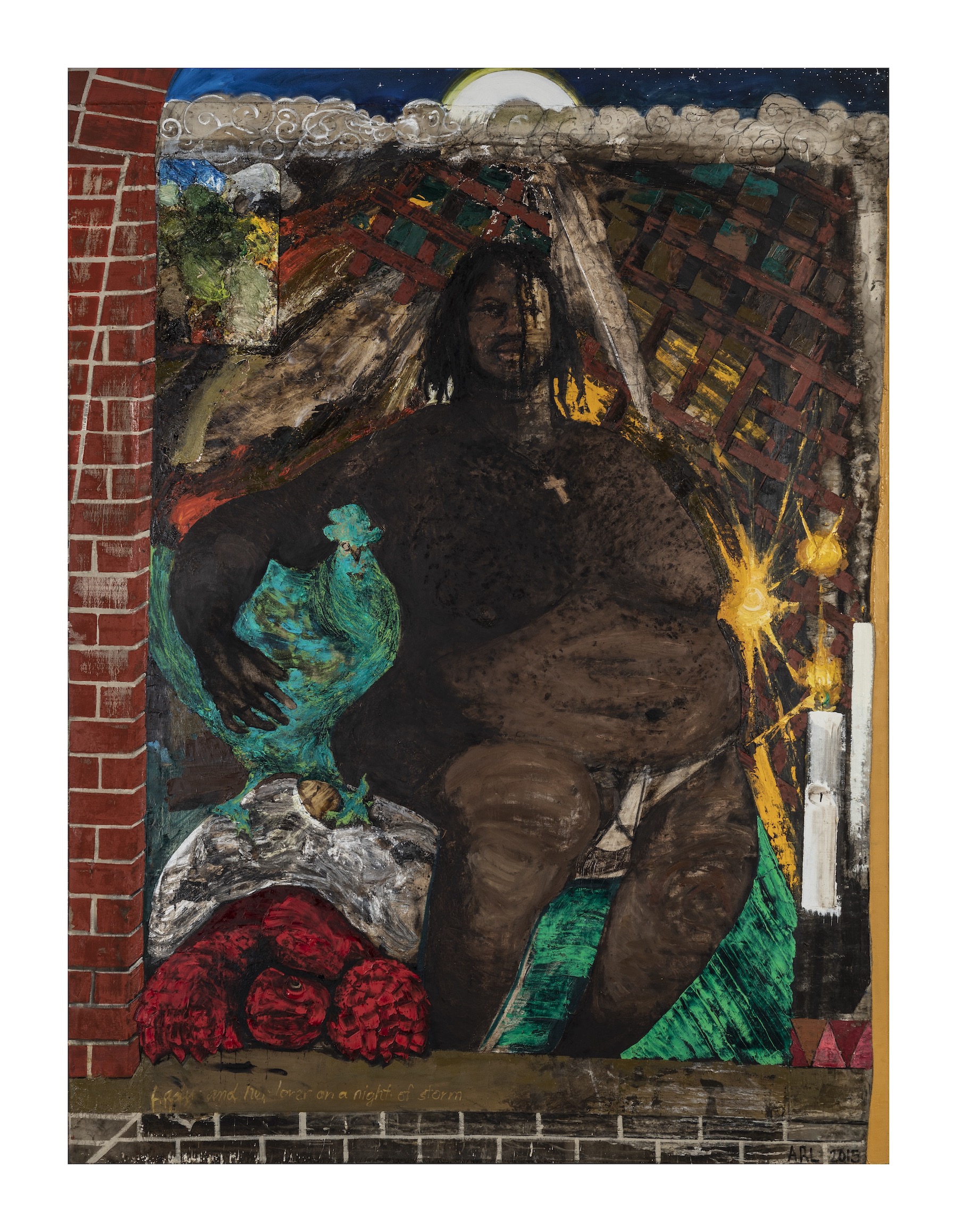

Del LaGrace Volcano is an intersex artist born in the US, but now living in Sweden. Their work chronicles the many faces of gender variation, and has done so for decades, long before the current cultural interest in trans identities. Seductively beautiful, the work is almost never shown in this country despite the artist’s many shows, and significant reputation, in Europe. In the Moj series, Volcano collaborated with their subject to tell the tale of an American woman, born a slave, who passed as a white man on the road to freedom. Canada’s most celebrated painter, Atilla Richard Luckas, is represented by a series of spellbinding paintings that, like most of his art, have also never been seen in the US. They depict, through a series of modern allegories, the artist’s rage and loss when his African-American partner Jermaine was sentenced to 16 years in prison for selling the very drug, marijuana, now legal in many other states. A painter’s painter, Luckas is among the most accomplished now working anywhere in the world, and his art is mesmerizing in its complexity, flawless execution and emotional power.

Hybridity, shift, metamorphosis—About Face seeks to capture a world culture in the midst of seismic changes around equality, sexuality, race, and gender. It presents a chorus of voices, but they aren’t singing the same song, as local conditions, needs, and politics vary widely. But there is another kind of beauty in this discord: the beauty of possibility, the sense that things are in flux, that identities are no longer solid and stable, but fluid and malleable. As always, art leads the way, representing even what’s not yet here or what’s not yet formulated, inchoate visions of a world to come, inklings of feeling that are too premature to concretize into words. About Face seeks to present these new visions, these new feelings, these new voices, a new Stonewall for a new millennium.