This week’s contributing blogger, Ilhan Ozan, is a writer and curator based in New York. He is currently pursuing his graduate studies at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. His research focuses on Turkey’s participation in international biennials between 1955 and 1987.

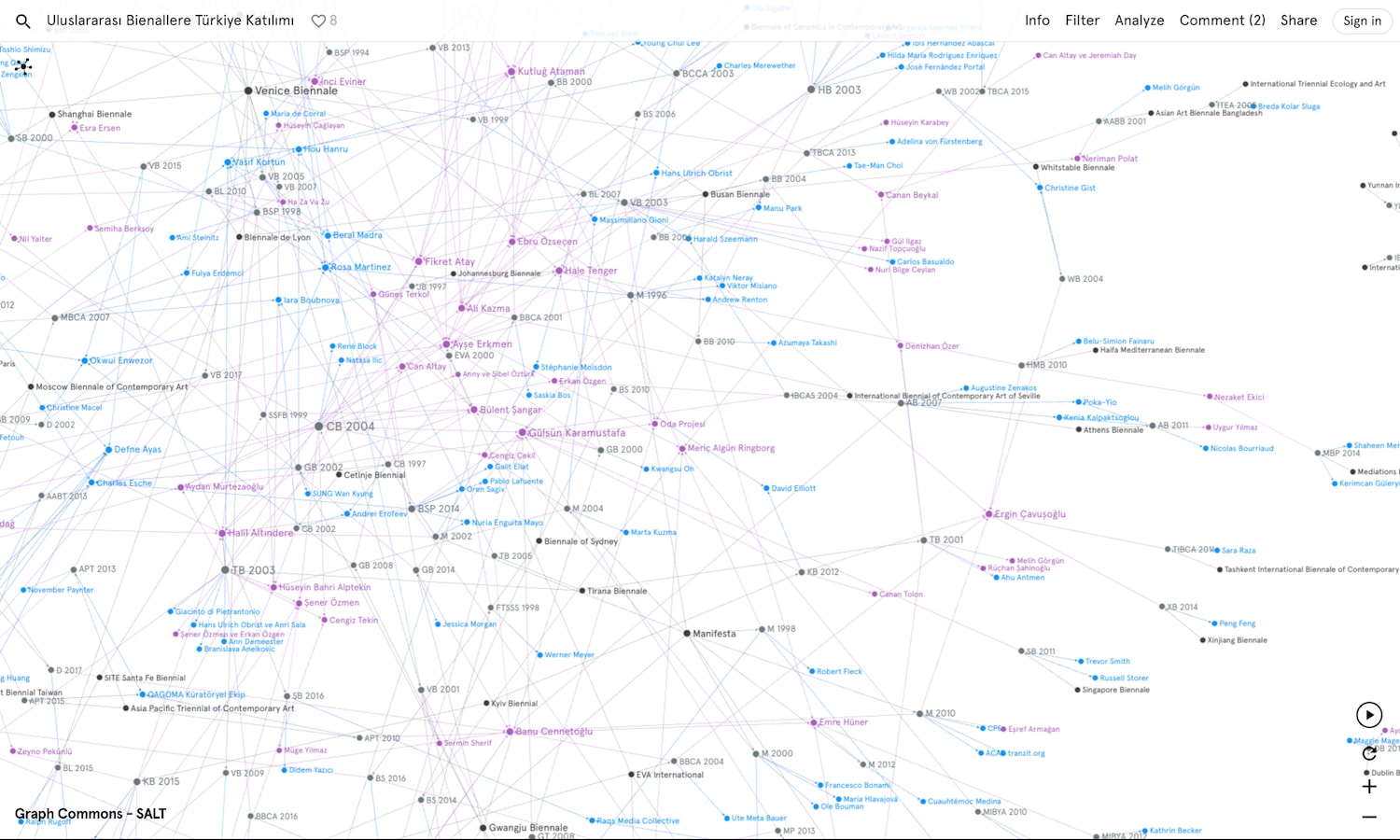

The field of digital humanities is increasingly becoming a more useful tool for the field of art history today. It can be quite effective for visualizing research and sharing it with the public, as it enables the viewer to look at data and interpret it from different angles, depending on the types of visualization and features of software. In this respect, a network graph published as one of the web projects of SALT Online that lists Turkey’s participation in international biennials throughout its history illustrates the advantages of using digital humanities in art historical research.

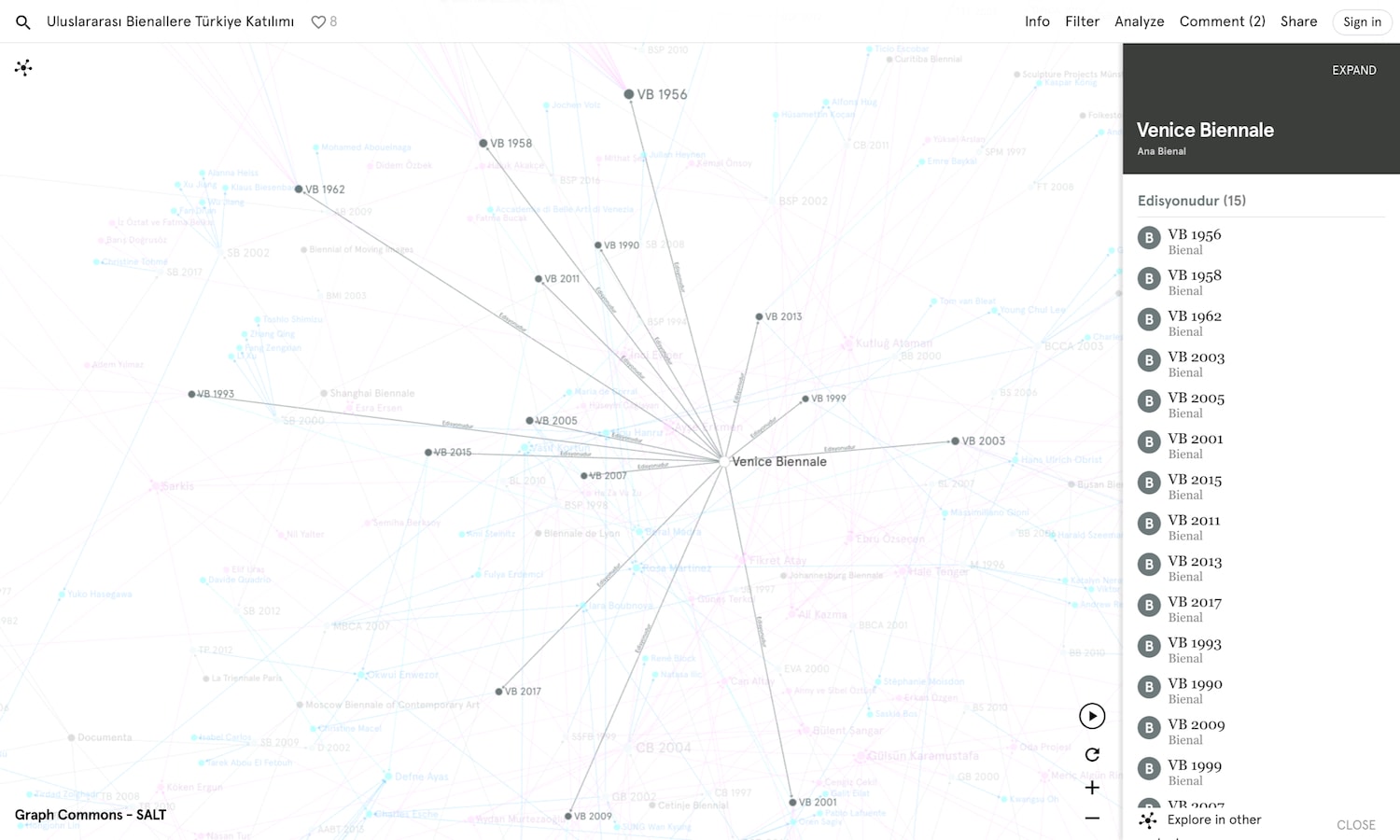

Created on Graph Commons, this network graph maps the national and individual participation of Turkish artists in international biennials. It starts with the first biennial Turkish artists participated in—the 1st Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts in 1955—and continues with the other biennial participation until the present. The data set consists of four variables: biennials, biennial editions, participating Turkish artists, and curators, in a total number of approximately a thousand values. Each value is displayed as a node in the graph, as the nodes are connected to each other through edges. In this network, a biennial edition node has the highest centrality, highlighting the relations among all related nodes.

The geographical diversity of the biennials enables the graph to trace the social, political, and artistic conditions in which they were held. In scholarly literature, the history of biennials is often studied vis-à-vis contemporary art, focusing on the biennials that were initiated after the mid-1980s when those such as the Havana, Istanbul, and Johannesburg Biennials come into prominence. One of the distinctive characteristics of these biennials is their tendency to act as a catalyst for the development of contemporary art in non-Western regions, and the transformation of exhibition practices at large. Nevertheless, the existence of biennials in non-Western regions from the mid-1950s through the late 1980s is usually overlooked in the scholarship on the history of biennials despite their scale and significance. As seen in the graph, this period of biennials, which can be referred as the first wave biennials, includes the biennials of Ljubljana, Alexandria, Tehran, and the triennials of Belgrade, India.

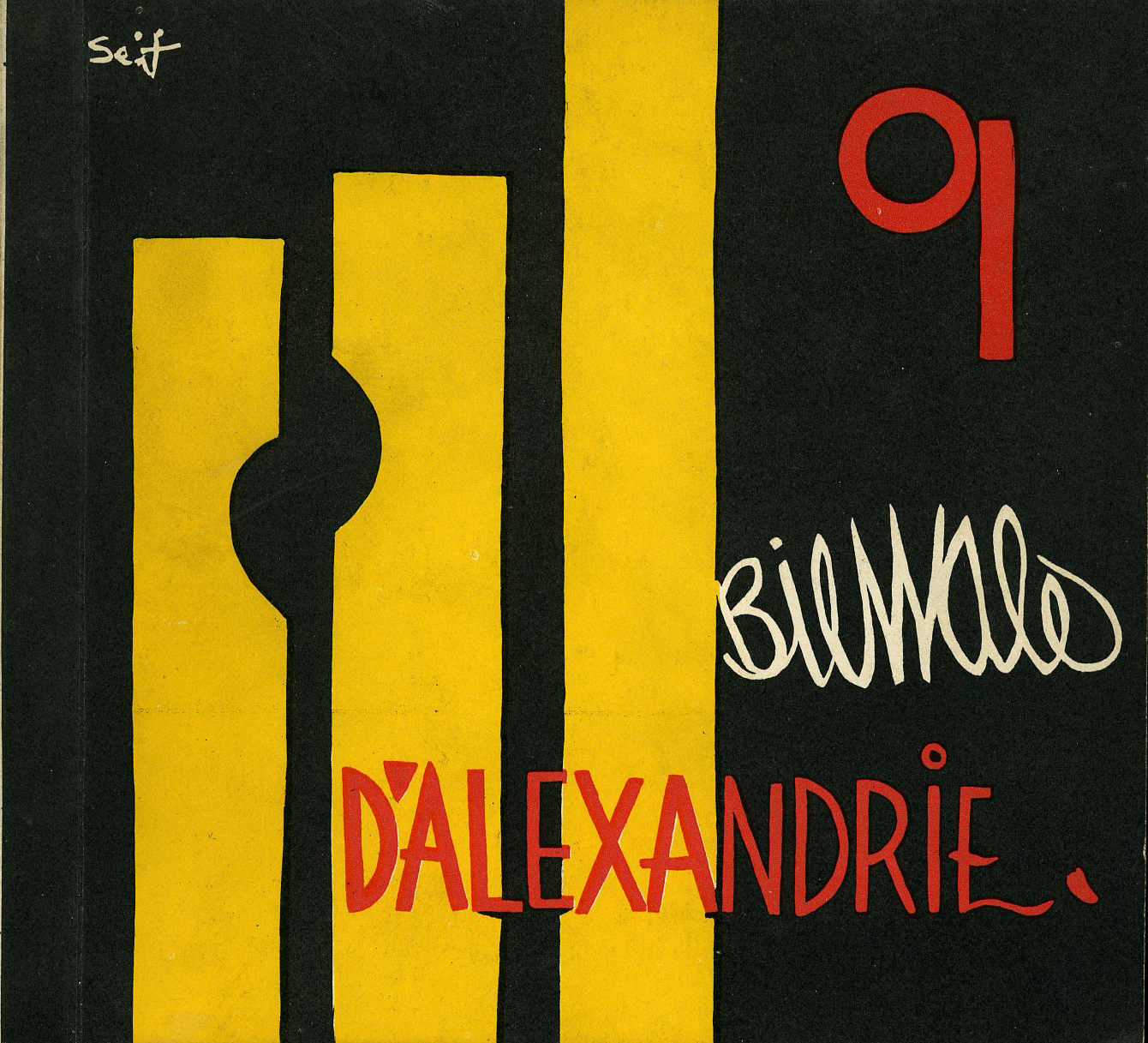

A remarkable aspect of the research structure is its method of mapping these biennials through the participation of a particular country, in this case Turkey. For example, the first wave biennials were realized as a token of cultural diplomacy during this period, which corresponds to the Cold War world order and politics, and accordingly, each biennial organization represents a geopolitical formation. The best case exemplifying this point might be the beginning of Turkey’s participation in Alexandria Biennial. Although Alexandria Biennial was initiated in 1955, Turkey’s first participated in 1972 as a result of changing diplomatic relations between the two countries after Gamal Abdel Nasser’s presidency in Egypt.[1] Pursuing the history of biennials through a country’s participation therefore steers the exhibit of art towards a transnational and transregional frame, pointing to factors other than the works themselves, and the agents other than the artists.

The catalog cover of the 9th Alexandria Biennial organized in 1971/72 and included the first participation from Turkey.

Moreover, the specific Turkish artists in these biennials can shed light on the internal dynamics of the art scene in Turkey. Most of the artists from the biennials of the 1950s and 1960s are in fact from the circle of the State Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul. For instance, the established figures of the Academy, Nurullah Berk and Sabri Berkel, appear to have organized most of the participations in these decades such as Paris Biennials in 1961, 1963, 1965, 1967; Venice Biennials in 1956, 1958, 1962; São Paulo Biennials in 1957, 1967, 1969; and Tehran Biennial in 1966, while they showed their own works along with those of their fellow artists and students. But, when looking at the artists in the later biennials, one can see that the historical monopoly of the Academy was fading. This may suggest the establishment and development of other institutions for art education as well as new channels connecting the artists with the main biennial organizers. Another conclusion about the artists that can be drawn from the graph is gender distribution. A gender analysis demonstrates that while the ratio of women artists participated in these biennials are 11% between 1955-1986, it increases to 35% between 1987-2007, and then to 45% between 2008-2016.

Graph Commons has integrated “filter” and “analyze” features that are found on the upper right corner of the graph. The former feature allows the users to set a timeline for the desired period along with the option of selecting or isolating node types, thus enabling one to view a specific period and group of constituents in the overall graph. The latter feature, on the other hand, shows the clusters on the map, indicating the number and total percentage of the connections related to a particular node. For instance, the 5th Tehran Biennial in 1966 (node name TB 1966) has the highest cluster with 106 nodes (12%), which also includes the secondary connections. Hence, clusters cumulatively measure the connections, and display the nodes by their centrality degree in the overall network.

Consequently, this network graph provides a factual basis for asking questions about sociopolitical circumstances, institutional contexts, and art forms of the last 60 years in both national and international levels. It is still an ongoing project, and its content can be digitally expanded with further information such as artist’s biographies, images of the works, and various archival materials from the biennials. It may possibly have missing biennials or artists because of the difficulty of accessing archival documents especially from the early biennials. However, it is an advantage of publishing a research in public domain that the content development is open to contributions from the public.

In this respect, collaborative research projects in digital humanities lead to the development of new knowledge, and their visualization can help facilitate further collaboration. While the users can comment for additions and corrections, the research conducted and visualized here can potentially be beneficial for other researches by presenting an initial framework.

To visit the network graph, go to https://www.graphcommons.com/graphs/4b59f010-dd53-4f38-9b69-8aa634bcb398.

[1] While the historical relations between Turkey and Egypt are one reason for Turkey’s absence from this Biennial, the alliances of the two countries with the opposing poles during the early Cold War is likely to be another factor. In this regard, the 5th Tehran Regional Biennial (1966) can be considered as a counterpart to Alexandria Biennial, since it included participations only from Turkey and Pakistan together with Iran. Thus, a comparative perspective on these two biennials broadly reflects the political tensions between the Arab and non-Arab Middle Eastern countries as well as the First World and the Second World alliances.