This week’s contributing blogger, Beau R. Ott, is a private collector of primarily American abstract paintings and sculpture from the 1960’s. He is an avid researcher with an acute interest in the history of mid century art as well as a specific interest in the preservation and conservation of plastics and kinetic art. He has recently loaned works from his collection to The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The National Academy Museum in NYC, The Georgia Museum of Art, and The David Zwirner Gallery in NYC to name a few.

The recent conference Keep it Moving? Conserving Kinetic Art was held at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, Italy from June 30 – July 2, 2016. My wife and I began the week with a few days in Venice before heading west the day before the conference. We stopped in Modena and Maranello to see the Ferrari museums and factory given our appreciation for the sheer beauty of the automobiles and their well earned position in Italian culture. I didn’t anticipate that a comment by our tour guide would begin the kinetic conservation conference a day early for me. Our guide mentioned that many of the cars in the Ferrari museums were on loan from private collectors because Ferrari had no interest in maintaining a collection of his past creations. Enzo Ferrari felt that “his best car was his next car”. He didn’t care to maintain the earlier models at all. In fact, he often cannibalized the earlier models for parts to be used on his newest creations. It was only after his passing in 1988 that the Ferrari factory opened a shop dedicated to the restoration and maintenance of the older models. A reasonable argument can be made for considering Ferrari’s automobiles as art, more specifically kinetic sculptures. Interestingly he began making his cars just before the mid-20th century, which also happens to be when the kinetic art movement began. Is it correct that Ferrari’s company painstakingly restores and preserves the sculptures when the artist himself outwardly expressed his interest in leaving them behind?

The Ferrari tour served as an introduction for me to the discourse that would be presented over the next three days related to the work of kinetic artists from around the globe. The artist’s intent of the proper presentation, preservation, and when needed, recreation of kinetic sculptures was only one part of the conversation. Who should have the final say on how kinetic art should be made available to future generations? Is it artists, estates, foundations, collectors, or conservators? There is generally agreement that the work should be available to future audiences but there are many questions that arise regarding the correct way to go about doing so. Here are some general points that I gleaned from the numerous broad and detailed presentations at the conference.

Kinetic art is defined as art that requires movement to achieve its intended effect. There are five ways that this movement can be created: 1) mechanical/motor (usually electric), 2) nature (usually wind or ambient air movement), 3) human interaction (often a gentle push), 4) implied (electric current moves from one light bulb to another, no physical movement occurs but the appearance of movement is present), and lastly 5) the movement of the viewer in relation to the art piece (such as in some of the work of Carlos Cruz-Diez and Fred Eversley).

Conservation of kinetic work may be required for safety reasons. Improper wiring or wires with old and cracked insulation may become fire hazards. The movement of some sculptures can be dangerous, especially if not regularly maintained, examples being Liz Larner’s Corner Basher that swings a small wrecking ball, Len Lye’s Flip and Two Twisters that spins long strips of flexible steel, or Gunther Uecker’s New York Dancer that could send nails flying through the air should any of them become loose.

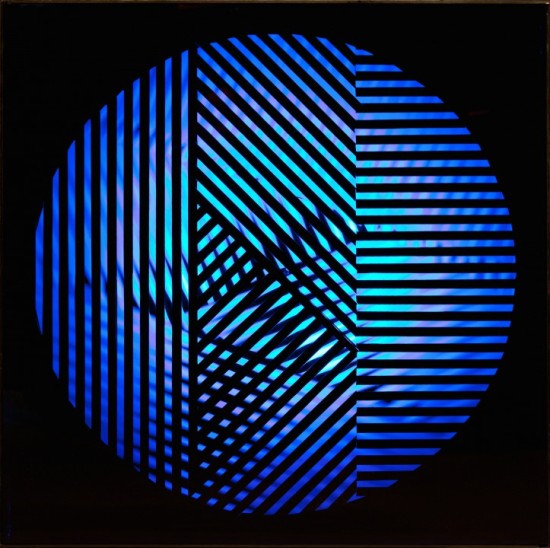

G. Varisco, Schema Luminoso Variabile R.R. 66, 1963/64, lighting scheme, 68.5 × 68.5 cm

When art is kinetic, the conservation focus includes not only the authenticity of the materials but, perhaps even more importantly, the functional authenticity of the work. How does one preserve the performance of a kinetic art piece while maintaining the originality of the physical materials used to construct the object? Movement causes wear which eventually leads to breakdown and ultimately to the loss of the performance. In many cases, conservation of kinetic art becomes a discussion of replacement parts and their availability.

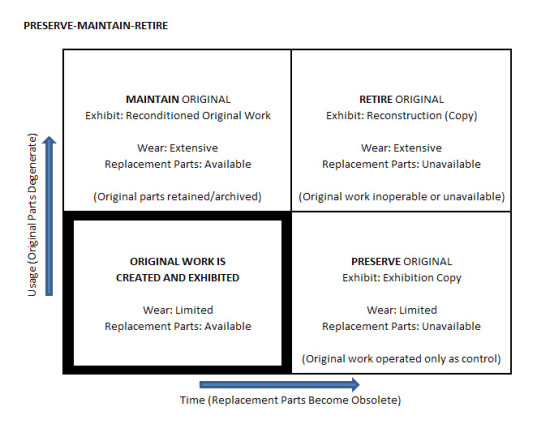

The presentations during the conference inspired me to develop a matrix that could be used as a guide for framing some of the discussions around the handling of kinetic art in order to “Keep it Moving”. Components of most kinetic art pieces that are exhibited in the manner that the artist intended become, over time, either worn out or obsolete, or both. Decisions around the proper care of the pieces call for value judgments that may vary from one conservator to the next.

1. Original Work is Created and Exhibited

Every piece presumably begins here when the parts used to make the piece are available and have limited wear. Whenever possible, it is a good practice to record the timing of any and all movement. Making a video record of the original work as it performs is ideal.

2. Retire Original

Most kinetic art is ultimately headed to this fate. Original parts become so worn that they fail to operate and replacement parts may become unavailable. When this happens, conservators (or artists themselves) have only the option of reconstructing a facsimile in order to allow future generations to experience the artist’s work. At this point, the original work becomes an artifact or a relic.

3. Preserve Original

Replacement parts may become more difficult to source over time. An exhibition copy may be a good way to replicate the performance of the original while limiting its wear. With this option, the original can be best kept in working order as a reference for the creation of future exhibition copies.

4. Maintain Original

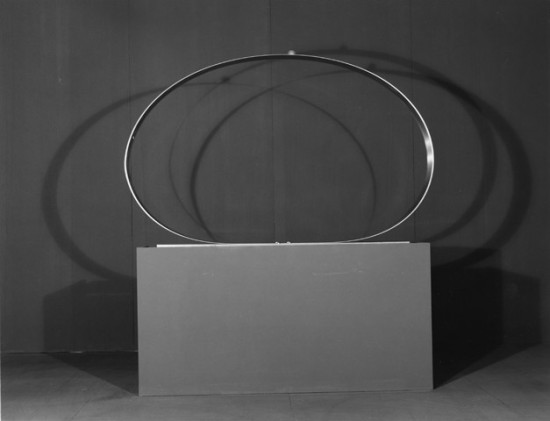

If replacement parts are available, the original work can be kept operational by replacing worn parts. The original worn parts should always be retained for later reference. Some artists (like Naum Gabo and Len Lye) planned that certain components of their kinetic works would wear out and have to be replaced.

Len Lye, Loop, 1963, Spring steel, two electromagnets, and cork ball, 60 x 72 x 6 in.

Collection of The Art Institute of Chicago

Planned to be on view late in 2016 or 2017

Lye intentionally placed his signature on the base of Loop and not on the spring steel band in anticipation that someday the spring steel band would have to be replaced

A value judgment is required when deciding between options 3 or 4. What is most important? Is it the experience of the original work itself or is it the preservation of the original work so that it will be available as a reference in the future? One thing that is for certain is that every kinetic art piece requires individual considerations regarding the most appropriate treatment. Even works completed by the same artist will vary in the availability of replacement parts as well as how the distinct parts will wear differently during normal usage.

Conservation of kinetic art is of particular interest to me. I feel that proper stewardship of these works is a responsibility that I am fortunate to have. At the conference, I was pleased to meet Simon Rees who represented the Len Lye Foundation and delivered a presentation on Lye’s work. Lye is one of my favorite kinetic artists whose work I am pleased to have represented in my collection. Another one of my favorite kinetic artists, for his art and as a person, is Fletcher Benton. Measuring ten feet wide and nearly six feet in height, Benton’s “R-1000” from 1968 is the largest kinetic work in my collection.

The last day of the conference provided an opportunity to see some local art collections including a behind the scenes peek at some of the amazing kinetic works in the collection of the Museo Del Novecento, which hosted the conference. Many thanks to the presenters who traveled from around the globe to share their knowledge and experiences with kinetic art made by many different artists from the early 20th century to the present. Also a tremendous thank you to the organizers of the conference: The Getty Conservation Institute, INCCA, ICOM-CC, and the Museo Del Novocento.