This week’s contributing blogger, Tatiana Ausema, is a Research Conservator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden and a PhD candidate in Preservation Studies at University of Delaware. Her research focuses on the materials and techniques of Morris Louis.

In May 2003, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden received one of the first conservation grants from the Morris Louis Conservation Fund (MLCF) to treat Louis’s 1959 painting Buskin. The proposed treatment was designed to prevent acid migration from the wood stretcher bars from staining the unpainted, unprimed canvas on the face of the painting, and to clean accumulated dust and grime from the face of the work. This treatment launched a long-term research project at the Hirshhorn that focuses on the care and cleaning of color field paintings, specifically the works of Morris Louis. Now, 10 years later, the museum is embarking on the final stage of this project and creating a living archive to aggregate and disseminate information related to the conservation of Morris Louis’s paintings held in public collections worldwide. This is the first in a series of occasional blog posts documenting the development of this archive.

“Buskin” (1959) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC,

Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1966

Morris Louis is an important figure in art history and conservation alike. He was the “founder” of the Washington Color Field school, placed as a key figure transitioning from abstract expressionism to color field painting, and eventually, minimalism. He is especially known for his technique of pouring diluted paint onto unprimed canvas, creating a stained effect. He was able to use this technique due to the introduction of Magna paint, the first synthetic marketed exclusively for artists. Like oil paint, Magna was soluble in turpentine, but unlike oil it could be thinned to water-like consistency without losing color intensity or clarity. Also, unlike oil paint, Magna could be poured directly on raw canvas without worrying about the synthetic resin yellowing, becoming brittle, or otherwise damaging the cotton fabric.

Point of Tranquility (1959-1960) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1966.

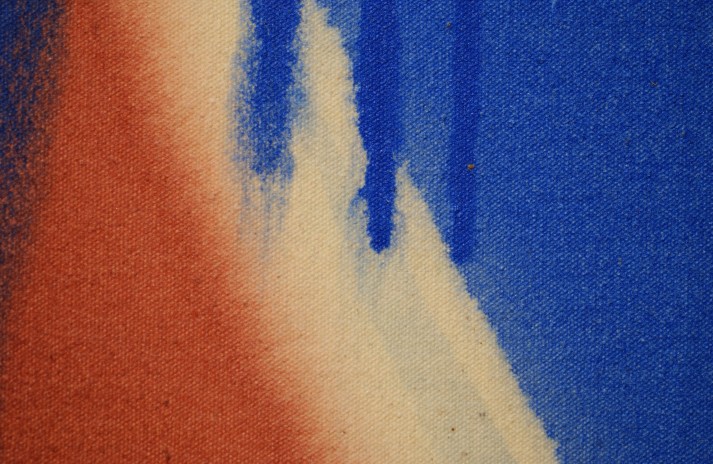

Detail of “Point of Tranquility” (1959-1960) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1966.

Part painting, part textile, Louis’s works have always presented a challenge to conservators. Many treatments appropriate for painted surfaces such as local cleaning with solvents, are ill suited to the porous, unprimed cotton. Treatments appropriate to textiles, such as overall immersion, are difficult given the enormous size of many of Louis’s canvases. Marcella Brenner, Louis’s widow, recognized these challenges, and established the Morris Louis Conservation Fund (MLCF) to ensure her late husband’s paintings would receive the best possible care. From 2003 to 2014, MLCF funded the assessment and treatment of over 25 of Louis’s paintings in public collections, with treatments ranging from preventive vacuuming and storage improvements to the complex removal of protective “varnishes” and overpaint.

Pamela Johnson vacuums the reverse of Gamma Pi (1960) during treatment funded by MLCF.

Image: Cathy Carver

In the decade that the MLCF granted funds for treatment, it has achieved unprecedented success both in regard to the treatment of Louis’s work and also as a model for future artist’s estates. The MLCF files contain a rich archive of written, photographic, and analytical documentation about the construction and condition of Louis’s paintings, and have fostered intense interest in the variety of methods and materials used to care for color field paintings. The archive documents experimental treatments, preventive care, and more traditional treatments, and allows scholars an opportunity to follow the long-term success and challenges associated with particular treatment methodology. Once the online archive has been completed, we hope it will also serve as a repository for additional research about Louis’s materials and technique, as well as research projects focusing on the care and preservation of color field painting.

As with many projects involving artist’s estates, the MLCF archive will strive for accessibility, while also respecting issues regarding copyright, ownership, and long-term sustainability. Over the next year, I will document the challenges and successes of the archive via the VoCA blog. Please follow along as we work to preserve the legacy of Morris Louis, and work to develop a model for other artists and artist’s estates.