This week’s contributing blogger, Rosanna Flouty, is an education professional with a commitment to building site-specific technology to support museum and arts-based programming. She is currently pursuing her doctoral degree in Urban Education with a focus on Interactive Technology + Pedagogy from CUNY Graduate Center, and is also a member of VoCA’s Program Committee.

“What is the role of the archive?”

“Who decides what is worth preserving?”

Good questions.

Recently, Lorraine O’Grady and a panel of esteemed arts professionals debated these and other topics in front of a packed audience at the Fales Library at New York University as part of VoCA’s ongoing Voice of the Artist series. As an artist who has charged herself with creating an archive of her own work, O’Grady posed alternative titles for the assembled panel, pointing to the complex relationship that performance and ephemeral works share with their own documentation.

O’Grady’s meta-analysis of the syntax in the description of the evening’s event cleverly accentuated the subtleties of language and linguistic emphasis, both of which can be as open-ended as the very concept of the archive itself. One such alternative included “Archiving the Future of Performance” – which for O’Grady offered a less passive vocabulary for understanding the function of the archive. She spoke to the way the archive creates limitations and sets standards for the performance of the future, as it literally “places it in a box” for safeguarding.

Gesturing between the podium and possibility, she felt that the archive is still here, and very much with us, while the possibilities for performance are still there, that is, full of potential for renewed interpretation and new work. She felt strongly that the word “FOR” made a more generous connection between present and future, as the archive exists not only for a future audience, but now serves a function for the very preservation of performance as a genre. By adding the word “for” as a preposition, the title of the lecture then becomes “Archiving FOR the Future of Performance,” a simple shift in diction that powerfully modifies the meaning and intent of the archival impulse.

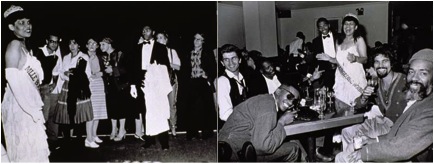

No archive of a performance can ever be complete – simply because it is rarely, if ever, possible to simultaneously document first-person perspectives of every performer, audience member or contributor. Images such as the two of O’Grady’s original performance of Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire (1980-83), shown here (and included Radical Presence), were widely reproduced without explanatory context over several decades, which poses the question: How does memory interject itself to fill in the pieces that are no longer there? It is uncommon that we come to a place where the archive is adequate. Does the “loss” result in melancholy, excitement, or something else entirely?

For Lorraine O’Grady, memory functions in her work as her process of transformation, but also as one of preservation. She readily admitted that gaps form, both intentionally and unintentionally through her process of making. Sometimes she has been asked to re-perform a work and has declined, especially, as she noted, if she had already learned what she needed to know or take away from the act of performance. This implies that the performance and its subsequent archive are not only for the viewer, but for performers as well; sometimes it needs to be selfish.

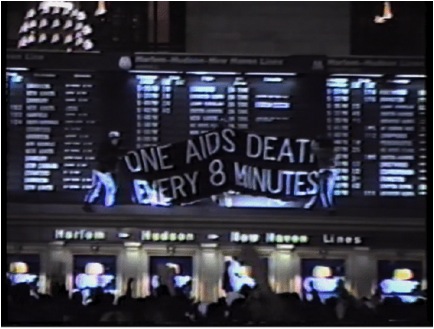

Archives, just like collections, are seldom neutral; rather they are full of lacunas, holes, pauses, and spaces. Panelist Lisa Darms spoke eloquently about how the Downtown Collection came to be in the possession of Fales Library, relating how a primary motivation of its donation, in part, was the ever-shifting sands of gentrification and death caused by the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s. A collection stripped from its context tends to exclude the unheard voices and lesser-known contributors of a movement, and museums exhibiting performance art seldom reiterate beyond the usual suspects. Realizing this made me wonder: Do such gaps cause sadness, or melancholy, or is that approach somehow overly sentimental? Rather, are we just impossibly “sexing” up the psychic power of possibilities for an archive?

To my mind, it is the vital act of preservation which serves to inherently create value for all artists: the more performances we preserve, the more options we create for future artists to choose from a pool of works through which to gain an understanding of historical precedent. We are left to contemplate a different kind of archive that must be considered for every performance, before we decide which one is most fitting and appropriate for an individual work. Here’s to hoping that it, too, can exist in multiple formats and in multiple archives simultaneously.

This Voice of the Artist program was held on October 3, 2013 in conjunction with the current exhibition Radical Presence, co-hosted by VoCA, The Studio Museum of Harlem, and New York University’s Grey Art Gallery. Program partners also included The Fales Library and Special Collections and New York University’s Department of Museum Studies.

Panelists who participated in this event were artist Lorraine O’Grady, conservator Glenn Wharton, archivist Lisa Darms, and curator Thomas J. Lax.