Contributing author Becky Fifield is the Associate Director for Collection Management for the Research Libraries of The New York Public Library. With over 30 years of collection experience, Becky holds an M.A. in Museum Studies from The George Washington University, and is a Fellow of the American Institute of Conservation.

In museums and libraries, it has become commonplace to refer to conservation, exhibition, and collections work as “behind-the-scenes.” This term is used to indicate that there is a world of activities going on beyond the public-facing galleries. Marketing and Development colleagues often use “behind-the-scenes” to generate excitement around the perceived exclusiveness of member events and fundraising opportunities.

Yet using behind-the-scenes to describe any aspect of cultural heritage work is at odds with increasing inclusion and engagement. Employing the phrase behind-the-scenes instantly draws a line and signals to visitors that museums and libraries — as well as our problematic legacies —control decision-making and priority-setting from behind closed doors, without them. By persistently using the phrase behind-the-scenes, we jeopardize the engagement we profess to seek, indicating that our work is secret, exclusive, and opaque.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan, “A Peep Behind the Curtain at Drury Lane,” by James Sayers, published by Thomas Cornell, etching and aquatint, published 14 January 1780, NPG D9542.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the phrase behind-the-scenes arose in the 17th century in the theater world to describe the trade secrets that generate what the audience experiences. OED definitions specify that behind-the-scenes indicates “out of sight of the audience” “in secret, away from public view or scrutiny,” or “designating activity taking place away from public view.” By the mid-19th century, behind-the-scenes was used to describe organizational activities that were secret and privileged. Museums were early adopters. In 1928, The Metropolitan Museum of Art created a film of workers in its various departments entitled “Behind-the-scenes: The Working Side of the Museum.”[1] The film features the work of not just curators and conservators, but also metal workers, sign letterers, and coal shovelers in a presentation of museum work that would be progressive on a modern museum website.

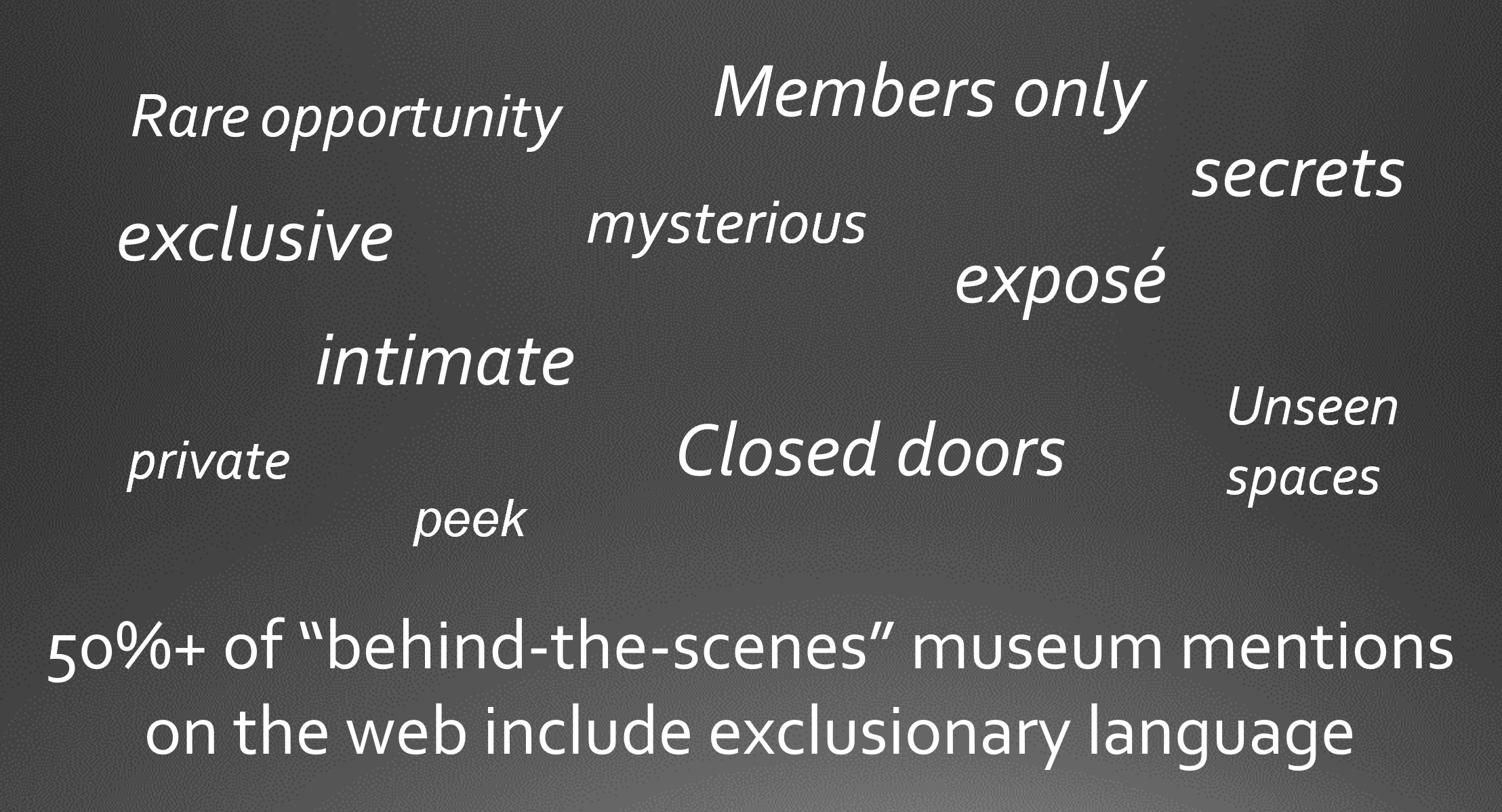

Potential visitors may first encounter behind-the-scenes online via websites or promotional language that aims to educate about museum activities or advertise events to engage with museum staff. A simple Google search in Spring 2020 for “behind-the-scenes,” “museum,” and “marketing” yielded at least 115 results, including descriptions of tours, blogs, and general museum work. Another search for “behind-the-scenes” and “conservation” yielded 55 additional examples. Fifty percent of the search results about conservation tours, events, and blogs included language that denotes exclusivity, including “private,” “rare opportunity,” “unseen,” “exclusive,” and “exposé.” Instantly, this language practice signals that there are barriers to participating in conversation about collection stewardship activities and with the workers who perform them. Where inclusion has lacked in museum collecting and engagement over the centuries, word choice can be critical in facilitating initial relationships with new audiences.

A Google search yielded over 50% of hits combining “museum” and “behind-the-scenes” also included language with a gatekeeping or exclusionary tone, such as rare, exclusive, and secret.

Major media, such as the British Broadcasting Corporation, National Geographic[2], and National Public Radio[3] have published focus pieces on “hidden” collections. An award for an exhibition about conservation was lauded for “conservation perspective/behind-the-scenes.”[4] About an in-gallery conservation treatment engagement experience, the lead conservator noted in The Washington Post that “People love these behind-the-scenes opportunities” even though the experience took place in public.[5]

This is an era where visitors expect to know more about our institutions. Social media is thick with snippets of experience creating new pathways of connection. Visitors want to delve into and see themselves in the research we perform, our engagement with the work of decolonization and repatriation responsibilities, the records we keep, the crazy stories behind our historic structures and the challenges we face to keep them running, the reckoning with white supremacy and exploitation that built many of our organizations, and meaningfully, the voices of museum workers. Behind-the-scenes may also be employed by marketing staff to jazz up core institutional functions they perceive aren’t that exciting or well understood by patrons (and marketing staff). In using behind-the-scenes, we are making our own frank admissions that we think our work needs set-dressing.

Consider these ways in which behind-the-scenes can do more harm than good.

Behind-the-scenes signals exclusion.

Behind-the-scenes immediately draws attention to the physical impediments audiences must overcome to engage with stewardship. Immediately, our audiences envision the walls and closed doors between physical spaces where they are allowed and those to which they are not admitted. As museum staff, we internalize these divisions in how we present the meaning in our own work. When we complain that we can’t fundraise for collection care, when we face complaints of collections locked away in “dusty storerooms”, when communities express disconnect with cultural institutions, can we honestly say that behind-the-scenes is a phrase we should be using to drive engagement?

Behind-the-scenes signals that differing value sets are not welcome as we seek responsible and respectful stewardship.

Behind-the-scenes emphasizes constraints around patrons’ representation and ability to engage with organizations that assume responsibility for caretaking of cultural heritage. It emphasizes who has control over stewardship, storage areas, and collection care practices, including inadequate cultural collection care.

Behind-the-scenes signals isolation from, and possible disregard of, other interconnected institutional functions.

All institutional staff are key to mission fulfillment in some way. However, it would be difficult to find a Facilities, Health & Safety, Procurement, Payroll, or Human Resources department that describe their work as behind-the-scenes. In adopting behind-the-scenes to describe collection functions, do we unintentionally devalue the work of key institutional partners?

Museums increasingly voice a commitment to valuing diversity and promoting equity. We must be mindful that the language we use to describe our work supports these goals. Think about how you describe your role: do you connect your role with your institution’s core values, outreach goals, mission statement, and diversity, equity, and inclusion goals? If the language we use to discuss our work signals barriers to inclusion, we risk alienating audience perspectives important for our organizations’ futures. Think about who you may need to partner with inside your organization and beyond to create inclusive messaging about museum functions and programming.

When I suggest that my peers stop using behind-the-scenes, they often ask: what do you suggest we say instead?

Let’s have our work speak for itself. Create amazing messages without behind-the scenes. Create opportunities of engagement that indicate open doors, exchange, and openness. Support colleagues in identifying the difficulties associated with the term behind-the-scenes. If Marketing or Development seeks to emphasize glamor or exclusivity, review outreach and engagement values in your institution’s mission statement or core values, and ask “does behind-the-scenes support our goals?”

When we celebrate diversity, who are we to say where the scene may lie in the experiences of our visitors? Where institutions and collections have been fostered in the public trust, all that our institutions are may be of interest. Let’s avoid creating unintentional barriers when our missions are to engage and inspire. Let’s not define our work as unseen; indeed, its results, perseverance, and dedication are seen every day.

It’s time to retire behind-the-scenes.

The author would like to thank Chris Norris, Director of Public Programs at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History for his ideas and insightful comments on this blog post.

[1] Behind the Scenes at the Museum,” British Broadcasting Corporation, last accessed September 28, 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00sfv9n

[2] Bill Newcott, “A rare look inside the Smithsonian’s secret storerooms,” National Geographic, November 23, 2021, last accessed September 28, 2022, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/a-rare-look-inside-the-smithsonians-secret-storerooms

[3] Harriet Baskas, “Hidden Treasures: Opening the ‘Public Vaults’,” National Public Radio, March 7, 2005, accessed September 28, 2022, https://www.knau.org/npr-news/2005-03-07/hidden-treasures-opening-the-public-vaults

[4] “Excellence in Exhibition Awards,” American Alliance for Museums National Association for Museum Exhibition, last accessed September 28, 2022, https://www.name-aam.org/award_2019

[5] Peggy McGlone, “The painstaking task of making a 200-year-old sculpture look almost like new.” The Washington Post. December 14, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/the-painstaking-task-of-making-a-200-year-old-sculpture-look-almost-like-new/2019/12/13/45e87484-1dd4-11ea-b4c1-fd0d91b60d9e_story.html