This week’s returning author, Marshall Reese, is an artist working in new technologies, video, installations, artists books and limited editions. He has worked in collaboration with Nora Ligorano as LigoranoReese for over two decades.

This blog post is part of periodic series from Reese that focuses on “outsider archivists,” people who highlight the tensions between traditional and born-digital archives and the transition between the two. Mnemosyne is the Greek goddess of memory, the mother of the nine muses. Her significance only seems to grow as we externalize more and more of information, data, and records.

Joan Logue’s Video Portraits

With the plethora of digital devices that saturate our lives today, it’s hard to imagine that there was a time, not so long ago, when seeing yourself, your family, or friends on an electronic screen was unfathomable. When artists began working in video in the early 1970’s, the closest model of what video art images could look like was broadcast television. The discourse of breaking those norms and the dynamics to propose video as a distinct art form animated the field for many years.

Few artists looked at the medium, though, in an intimate way. Joan Logue is one of them. Her ongoing five decades practice of video portraiture, worthy of much greater acknowledgement, has been preparing us for the world we live in now; a world of shared intimacy that we reveal of ourselves in moving images and stills privately and publicly on social media and in selfies.

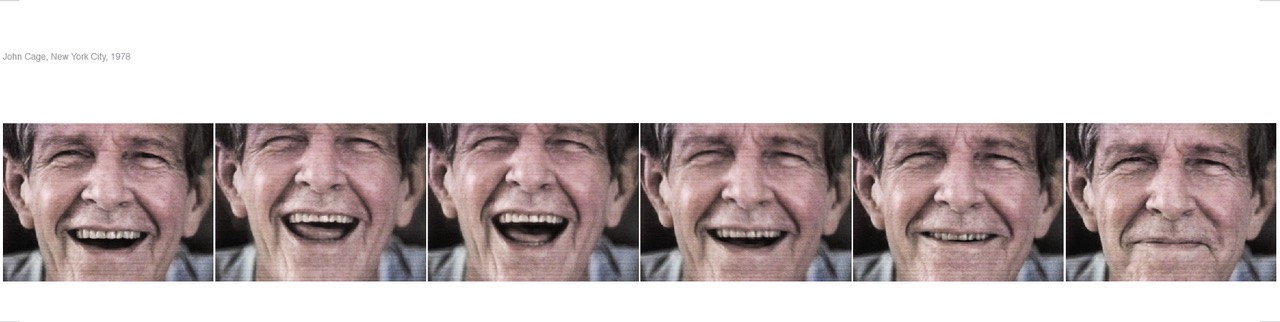

I first met Joan and saw her video portraits at the San Sebastian Video Festival in Spain in 1984. Joan’s portraits moved, breathed and lived. Her subjects looked into her camera, and peered out to reveal a presence and sense of being far more alive than had they been captured in still frames as a painting or photograph. The portraits of Laurie Anderson, John Cage, Robert Ashley, Nam June Paik, George Lewis and many others (dating from 1981-82) that she screened at the festival clearly related to television and commercials.

30-60 seconds in length, they were often aired as interstitial breaks on PBS’ Alive from Off Center and on European television. They were almost commercials except instead of advertising products, they featured contemporary artists and performers.

Joan’s approach to portraiture is expansive, taking in concepts of place and time. It makes sense to me that she began her groundbreaking work in West Africa in the early 1970’s. We spoke by phone about her work and how she’s preparing her collection soon to be acquired by the Centre Pompidou and Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. (In itself, a groundbreaking arrangement between the institutions as well as testament to the significance of her work.)

I was teaching video in a little village on the border of Sierra Leone and Liberia to men and women. One day, while cleaning the dust from my portapak camera, preparing for the day’s shoot, my camera was pointing out the window and there was this young child standing in front of my window. He knew that I was always carrying my camera around and he saw the camera and he saw me. He was going to duck below the window. And I motioned to him to stay – ‘No, no. Don’t move, just stay there.’

It was then I realized what I was seeing on the boy’s face in the video, you saw everything. It was the real portrait because you saw something beneath his smiling face. You actually saw the whole person without the facade! And I thought this is way better than any still photograph. And that’s when I started making video portraits.

Sense of place is significant in understanding Logue’s work. She makes not only moving portraits of people but also portraits of place. Her series on fishermen in Gloucester, Massachusetts, Spring Street shopkeepers in Soho, and villagers in Brittany, France capture her subjects pursuing their daily lives. There’s a quotidian sense and a sense of being centered.

Returning to California after Africa, Joan began doing video portraits of artists.

I would go to their studio. Ed Ruscha’s studio or Diebenkorn’s studio. I started in Judy Chicago’s. I would go and shoot them in their environment. Since they were all painters they understood the idea of silence, they understood when I asked them not to talk, This was in 1976, video art wasn’t what it is now, it was new and the equipment was heavy and very expensive.

On another level, Logue’s portraits are much more than representations. They’re feedback loops. They’re not just a recording of the subject, because the artist is also present in the making of it. Joan sits across from her subject next to her camera in silence. Her portraits are a silent meditation, a wordless conversation between two people.

My whole premise was that the silence was much stronger than the words. You actually got a sense of the person’s presence, who they were and how they felt. You don’t have an opportunity to sit with somebody in silence because everybody wants to fill that space with words. It’s difficult to be in silence with someone. In a way I’m as exposed as they are. When two people are confronted with silence, it’s like an acceptance of each other. You’re not arguing, you’re not schmoozing. The viewer and the sitter become one, because you both read each other.

Once you start a silent portrait, you feel the presence of the person and then the sitter kind of disappears into their head. You can see it in the portrait. Painters totally understood this. Whereas for writers it’s hard for them to, you know, not want to talk.

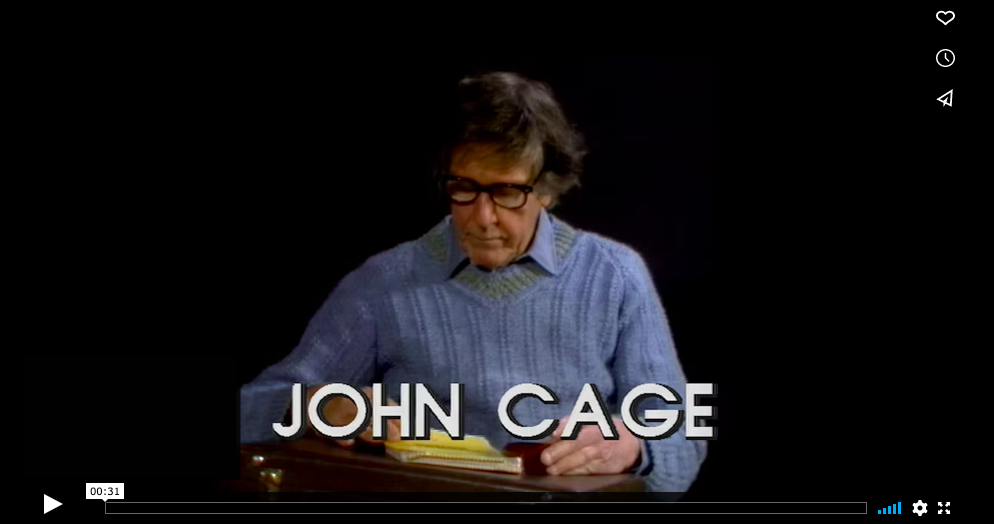

My favorite video portraits Joan created are those of John Cage. There are three: a short one and two longer ones. Her use of silence in her work, in fact, is how they met.

I was living at 110 Mercer Street in Soho where many of us lived at the time, Nam June, Shikego Kubota, Mary Beth Edelson, Yoshi Wada. And we didn’t have mailboxes. Everybody threw their mail on the staircase and periodically sorted through them to find theirs. I got this, John used to call them mailagrams. A “mailagram” from John Cage, was a take off on a telegram but this was John’s form of letter writing, a kind of short form he had printed to answer his correspondence.

John had sent me one and said, ‘Well, I heard you’re doing work in silence. I would like to talk to you.’ Everybody in the building knew this from going through the mail and called me, ‘Did you see, you got this thing from John?’ I said, ‘Yeah. Yeah.’ So I called him and he invited me over and we talked about silence. I asked him if he would do a portrait with me. And he said, ‘Yes’. So that was in 1979. I did one 30 second portrait of John Cage and I did two longer portraits, all silent portraits.

My fondest memory as a video editor for Standby is remastering Joan’s portrait of John Cage in the 1990’s. She had shot Cage on analogue videotape and we were in the process of transferring his portrait to digital video. It was late at night and we’d spent some time working together. At the end of the edit session I recall searching for the end frame of his video to fade out. And I couldn’t find it! There was no timecode number.

And then, trying to match the frame, I remember focusing intently on the video of Cage’s face, searching for some expressive change, for an end frame. To observe his incredible presence so intimately went far beyond the idea of traditional portraiture. I realized that the same thing that happened to Joan when she filmed her subjects was happening to me as the editor.

A process Joan elaborated on during our conversation:

I’m in the presence of them, you know. So they’re looking at me. I’m looking at them. All of a sudden the sitter who’s being focused on, looking at, you know, the viewer, me, the person who’s making the portrait, pretty soon, disappears. The subjects go interior, disappearing into their own thoughts. So in the process of the 20 minute silent video portraits, their faces first are alert, curious and engaging. Then there is a slow change to what becomes visible.

You can see it on everybody’s face when that happens… they start to reveal an interior portrait of themselves. After 20 minutes is about over, their usual presence returns. I can see them exhausted and ready to stop.

There are over 1,400 videotapes in Joan’s collection. The sheer number of formats would be their own history of the technological development of video and television, including half-inch open reel, U-Matic, One-inch, DigiBeta, VHS, Hi8, Betacam, and digital video. Over one ton of Logue’s video will soon join the collections of the Biblioteque National and Pompidou Centre in Paris where she did much of her work in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Preparing the collection for its next stage has been a labor of love.

Mona Jimenez, Associate Professor Emerita of Cinema Studies at New York University suggested to Joan that they initiate an archival project with her students Athena Holbrook and Joey Heinen. (Holbrook and Heinen currently are collections specialists in the New Media Departments of MoMA and LACMA, respectively.)

Athena and Joey came and spent two years going through everything. They went through all of it. Multiple formats. They looked at every tape to see if it was in shape for migration or damaged.

Video by its nature is easy to copy from one tape or version to another. This is known as tape generation, which also, until recently, degraded image quality, sometimes significantly, which is why final edited versions are called “masters”. Archivists make special efforts to find the original version of the tape for the best quality image. It was important, therefore, for Athena and Joey to examine Joan’s collection very closely, to understand and organize it from that perspective to facilitate the next stage of the process for determining what videos were suitable to digitize.

Athena and Joey discovered different versions and edits of many of the same works. They also learned that Joan used camera originals as masters for some of the final video portraits. The archivists organized her collection accordingly by format with a color-coding system that correlated to image generation. And they also assessed the tapes for any wear and damage.

Joey and Athena found only one damaged tape – out of all the tapes. A one-inch reel to reel tape that styrofoam got stuck onto the tape dating from 1982, when I shot it over 30 years ago. It was incredible that there was only one tape that couldn’t migrate.

Along with her tapes are detailed ephemera about each portrait.

Not just my notes. The notes of the shoot. The notes in my journals. Any texts written about any of the exhibitions, about the 30 second pieces. I mean, who knew about keeping meta-data, who knew that word back then?

On the walls of the Pompidou Centre in the Biblioteque National, viewers will see Logue’s living portraits hanging in the galleries. They will enter a real electronic portrait gallery, a dream that Joan has been working on for many years.

My reasons for making the long portraits were to eventually replace paintings. Even though they were shot 50 years or 40 years ago, you still have the presence of the subject’s present. I want the public to see a whole exhibition of them and fill the galleries with long portraits and short portraits. A new portrait gallery filled with the living, breathing presences of my subjects.

Note: All quotes are taken from a phone conversation with the artist and Marshall Reese from May 2, 2022.