Contributing authors Olivia Wang, Ashley Kromah, Maya Read, and Katherine Brady all attend Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. Olivia is a first-year student studying design. Ashley is a second-year student studying Game Art and Animation. Maya is a fourth-year student studying Philosophy and Economics. Katherine is a fifth-year student studying Business Administration and Marketing.

VoCA is pleased to present this blog post in conjunction with Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History, Gloria Sutton’s Spring 2022 Honors Seminar, The Art of Visual Intelligence at Northeastern University. This interdisciplinary course combines the powers of observation (formal description, visual data) with techniques of interpretation to sharpen perceptual awareness allowing students to develop compelling analysis of visual phenomena.

Fidelity Investments is a multinational financial services company with $4.2T assets under management. Headquartered in Boston, MA, Fidelity has a corporate presence across America, Asia, and Europe, as well as a robust private collection of art that is displayed throughout their offices worldwide. In March 2022, Patricia Dellorfano, the Head of Fidelity’s Corporate Art Collection, spoke with a class of Northeastern Art History students about her work in the corporate art world. The following interview draws upon Patricia’s expertise to explore the current relationship between contemporary art and the corporate environments.

As the curator of the collection, how do you and your team bring works into the collection? How do you maintain, conserve, and manage such a vast enterprise while also addressing both a local and global audience?

Fidelity’s collection has about 12,000 pieces, which is approximately the size of a medium-size museum. Fidelity actually models its structure on the operations of museums. We have a registrar, as well as people specifically devoted to the curation of and logistics for the collection respectively. We aspire to collect museum-level works and consequently approach the conservation and care of the collection methodologically. The firm does not aim to acquire pieces of art as investment opportunities. The collection is valued solely for its contribution to the Fidelity experience. Corporate collections are only as robust as the interest from the current executives at the firm. Fidelity views its collection as a form of corporate citizenship through its commitment to the local communities where they have a presence. My team of curators use art fairs, studio visits, and word of mouth to acquire works that fill this brief.

Fidelity’s collection contains a mix of emerging, mid-career, and established artists. What are the qualifications you look for when purchasing art for the collection? How have the priorities of the collection changed over time?

As a privately owned company, the Johnson family who established Fidelity Investments had a great say in the direction of the company and the launch of the collection. The first acquisition, a 19th century bronze study by Augustus Saint-Gaudens titled The Puritan, paid homage to the family’s puritan roots but the company and by extension the collection has grown exponentially as times have changed.

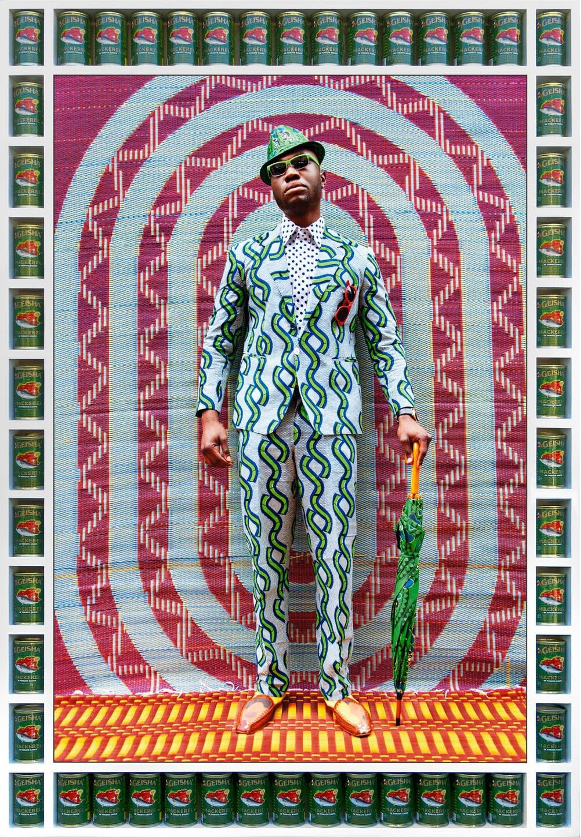

Today, Fidelity works to veer toward true contemporary art. There is a focus on art being made today— ideally that is relevant or speaks to the customers, clients, visitors, employees, and people who are in Fidelity spaces. Since our company is not a museum, our audience is not necessarily composed of people who have bought into the value of appreciating art and thus we prefer to focus on the art itself rather than a target viewer. Fidelity’s status as a corporate art collection makes acquisitions occur at a rapid pace. The collection adds about 500 new acquisitions a year from all types of media. One of the newer acquisitions to the collection from 2021 include a portrait photograph titled AFRIKAN BOY STANDIN’ from Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj. With no oversight committee and no harsh qualifications, my team and I are able to explore, find, discuss, and handle these acquisitions. We constantly discuss our curatorial criteria to consider where gaps are in the collection and problem solve for the kinds of spaces we have to fill all while paying attention to current trends and concepts to stay true to our focus on contemporary works.

Right: Hassan Hajjaj, Afrikan Boy Standin’, 2012/1433 (Gregorian/Hijri), Metallic Lambda on 3mm Dibond in a Poplar Sprayed-White Frame Green “Geisha” Mackerel Cans, 53 3/8 × 37 × 2 1/2 in, Edition of 5 + 2AP

What are your policies on how sensitive topics are portrayed within the workplace? Out of all the pieces that you’ve sourced, is there one that posed the greatest challenge in this regard?

As Fidelity Investments is a large company with a significant reputation, some self-censoring is involved when approaching hot-button topics like gender, race, and sexuality. While Fidelity doesn’t actively try to avoid these topics, more conscious methods are required when adding such pieces to the collection. A major part of this includes reaching out to ERGs, or employee resource groups, to collect feedback on how certain art pieces will impact larger audiences. For example, when deciding whether to purchase Baseera Khan’s Mosque Lamp and Prayer Carpet Green from Laws of Antiquities, a 60” x 40” digital print of a collection of Islamic artifacts and architecture, I reached out to a Muslim-centered ERG to ensure the piece is culturally sensitive before purchasing.

How does Fidelity preserve the artist’s intent when displaying their pieces in a corporate setting?

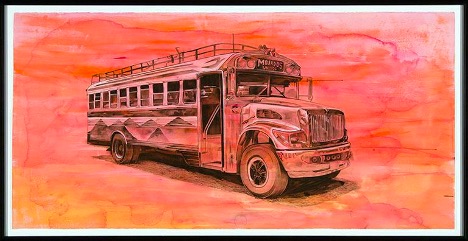

While great lengths are taken to prevent miscommunications in curated art, I recount an instance where one piece proved to be unexpectedly controversial. Mojados Unidos by Raul Gonzalez III, a Mexican American artist who grew up in Texas, features a watercolor landscape with a bus. On the bus displays the word “wetback” in Spanish, a derogatory term often used to refer to illegal Mexican immigrants. Being of Mexican American descent, Gonzalez was motivated by the differences he witnessed growing up near the Mexican border in Texas. Despite my precautions in choosing this piece, which involved consulting Hispanic heritage ERGs, it received negative feedback, resulting in the removal of the piece from the corporation. This is a significant example of the fine line that I walk when curating pieces for Fidelity.

Often, discussions about contemporary art only enter the public sphere when there is auction record, a controversy, or when it divides audiences. Yet the Fidelity Art Collection’s impact statement emphasizes the collection’s aim to catalyze creativity and connect people. How the contemporary artworks in your collection inspire or provoke conversation or connection? Why should corporations value contemporary art for its ability to “catalyze creativity and connection” rather than only its monetary value?

Mr. Johnson, the former chairman, recently passed away and his children are now at the helm. They’re generally supportive of these contemporary gestures. I think they’re really proud of the fact that we’re out and about working with artists in local communities. That moves away from what you reference, which is the sensationalized aspects of this very glamorous art market. People hear about the scandals, the thefts, and the ridiculousness of it all and love to make examples of these really extreme situations, whereas our collection hums along at a non-controversial pace, where we’re really just working with area artists and buying art that is quite often at a fairly low price point.

We get a lot of examples of people who feel like they felt safe; like they could talk about the art. People who come in for interviews say, “I was walking down the hall, I noticed that cool art and I thought oh my gosh they’re really plugged in— they know what to do, and it was part of the reason I took this job.” It can help establish a reputation that a company can have a cooler and unexpected side. Fidelity partners with employee resource groups, which are social groups that gel together a group of like-minded people, to foster deeper conversations and advocacy around their missions. For example, there’s a group for veterans or people who have family members in the armed services, a group for African Americans and an LGBTQA+ group. Over the past few years, we have worked hard to co-program with the groups, so we listen to them to hear about the issues they’re discussing and then bring art in as a tool to launch those discussions. The creativity happens when people get inspired by a work, the connection happens when people feel close to each other through a work. We have a really robust website and online gallery that anyone in the company can see and comment on. There is an employee art gallery, and we blog daily, do virtual art tours and list all of our art events. Unfortunately, because Fidelity’s private it is internal.

This collection is truly activated through context and programming, not unlike a gallery or a museum. We will purchase this art, care for it, frame it lovingly and hang it on the wall, but that’s half the job. I feel really passionately that we also offer deeper tools— whether it’s an artist coming in talking about their work or whether it’s someone coming in and offering a painting lab. That idea of like keeping the conversation going, it has to go beyond the art piece.