Mark I. West is a professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he teaches courses in children’s and young adult literature. He is especially interested urban children’s literature.

I recently visited Faith Ringgold: American People, the New Museum’s retrospective exhibit of Ringgold’s art. I was looking at Ringgold’s two Tar Beach quilts when I flashed back to a graduate seminar I taught on urban children’s literature, where I devoted an entire class session to picture books set in cities, including Ringgold’s Tar Beach. Wanting the students to experience this picture book in the same way that young children usually do, I opened the book and started reading out-loud about eight-year-old Cassie Louise Lightfoot and her love of spending time on the roof of the tenement building where she lives with her family. In that moment, I was reminded of an old Motown hit by The Drifters called “Up on the Roof” that I listened to when I was young. The song is about escaping the “hustling crowd” and “rat race noise” by climbing “up to the top of the stairs” and spending time in the “trouble proof” space “up on the roof.” This summary of the song equally applies to Ringgold’s Tar Beach, but Ringgold’s story goes beyond the theme of escape to explore ideas of imagination and empowerment.

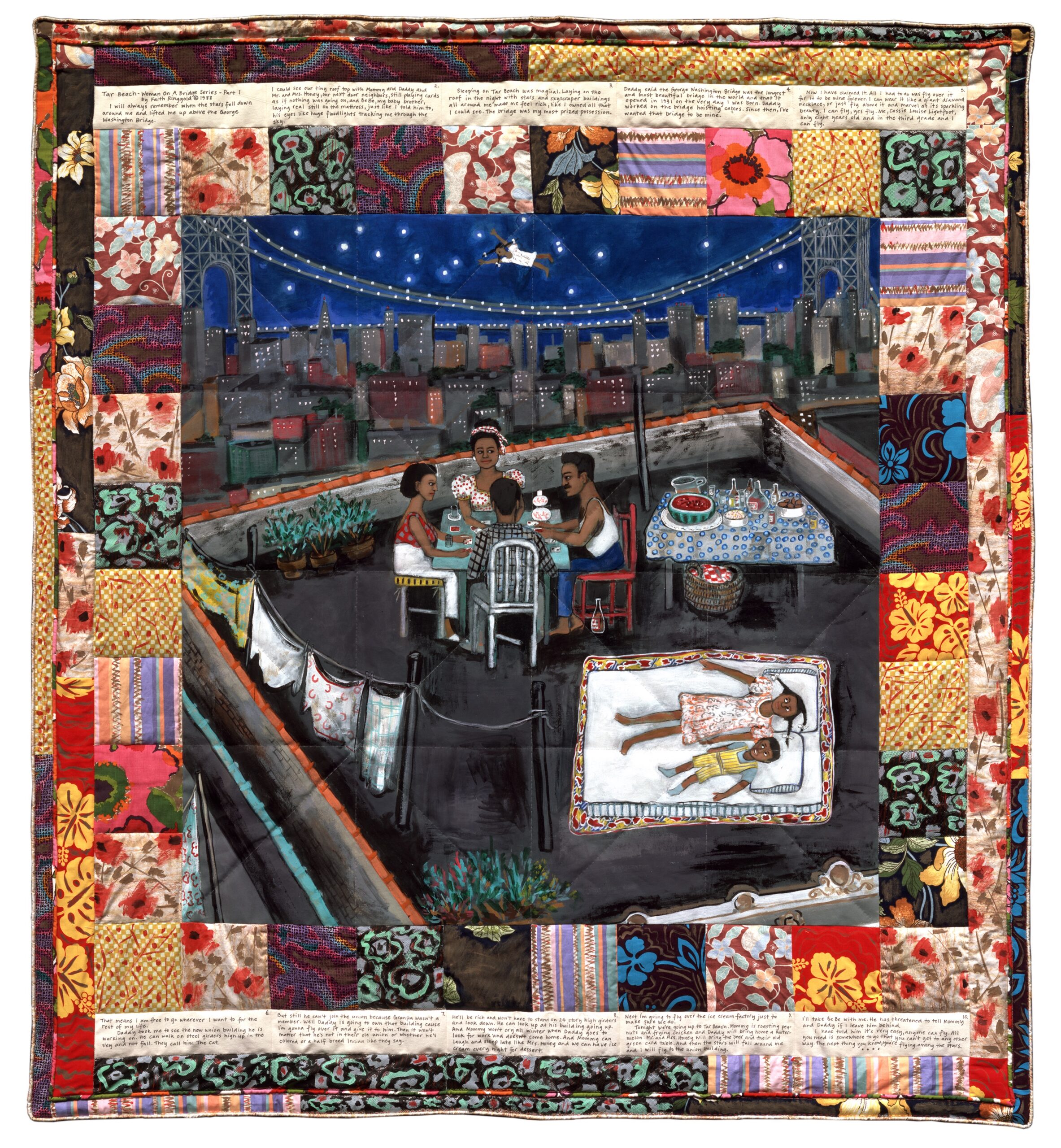

The publication of Faith Ringgold’s Tar Beach in 1991 launched her career as a children’s author, and it was an auspicious debut. She received both a Coretta Scott King Award for Illustration and a Caldecott Honor Award for the book. However, her career as a professional artist can be traced back to the mid-1950s when she began creating oil paintings. In the 1970s, she took an interest in fabric and textiles and achieved recognition for her story quilts. In creating her story quilts, she combines painting, patchwork quilting, and sequential images. Many of the story quilts also also include hand-lettered narratives that accompany the visual images.

“Faith Ringgold: American People,” 2022. Exhibition view. New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni

In the late 1980s, Ringgold started work on Woman on a Bridge, a series of five story quilts that all include images of the George Washington Bridge. For much of her life, Ringgold has lived within sight of this bridge, and she often thinks of it as her bridge.[1] She finished Tar Beach, part I of this series, in 1988, and she completed Tar Beach II in 1990. Both of these story quilts include panels of text about a girl who has a special connection to the George Washington Bridge.

Ringgold incorporated many of the visual images and textual panels from these two quilts when she created her Tar Beach picture book. These story quilts and the picture book versions of Tar Beach relate to Ringgold’s childhood in Harlem in the 1930s. The central character in these versions of the story, Cassie Louise Lightfoot, is largely based on the author and her memories of her childhood.[2]

In the book, Cassie relishes the time she spends with her family and next-door neighbors on their “tiny rooftop,” which she calls her “Tar Beach.” Her parents put a mattress on the rooftop for Cassie and her little brother to sleep on while the adults are visiting and playing cards. For Cassie, “Sleeping on Tar Beach was magical. Lying on the roof in the night, with stars and skyscraper buildings all around me, made me feel rich, like I owned all that I could see.”[3] In the context of the story, Cassie fantasizes that she can fly. The illustrations depict her soaring above New York City, claiming the George Washington Bridge and other landmarks as her own.

Faith Ringgold, Woman on a Bridge #1 of 5: Tar Beach, 1988. Acrylic paint, canvas, printed fabric, ink, and thread, 74 5/8 x 68 ½ in. (189.5 x 174 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Gift Mr. and Mrs. Gus and Judith Leiber, 88.3620. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022

Ringgold portrays the rooftop as a liminal space where reality and fantasy merge. On the one hand, the roof is a place where the family eats dinner and socializes with the neighbors: “Tonight we’re going up to Tar Beach. Mommy is roasting peanuts and frying chicken, and Daddy will bring home a watermelon. Mr. and Mrs. Honey will bring the beer and their old green card table.”[4] On the other hand, the roof functions as the launching pad for Cassie’s night flights around the city, symbolizing a safe space where she feels secure enough to let her imagination take flight. In her fantasies, Cassie is able to help her father overcome the real-world discrimination he faces because he is half African American and half American Indian; in turn, she feels good about herself because she can make life better for her whole family. Her dreams correspond to a point that Bruno Bettelheim, a psychoanalyst and author of The Uses of Enchantment, makes about the healing power of fantasy: “While the fantasy is unreal, the good feelings it gives us about ourselves and our future are real, and these real good feelings are what we need to sustain us.”[5]

For Cassie, her good feelings are inextricably linked to the time she spends on the rooftop. The story concludes with Cassie introducing her younger brother, Be Be, to her fantasy world: “I have told him it’s very easy, anyone can fly. All you need is somewhere to go that you can’t get to any other way. The next thing you know, you’re flying among the stars.”[6] Ringgold portrays the Tar Beach as a recuperative space where Cassie feels safe, can let her guard down, engage her imagination, and cultivate her sense of self-worth.

For visitors to the New Museum’s retrospective exhibit of Ringgold’s art, the experience of immersing oneself in Ringgold’s paintings and quilts is also like entering a liminal space. So many of her works relate to the history and culture of New York City, but Ringgold’s depictions of New York take on a personal quality. Just as Cassie does in Tar Beach, Ringgold claims New York City and, by extension, America for herself through her art. Ringgold’s depictions of New York relate to her own experiences in the city, but they also celebrate the vibrancy of Black culture. In related works such as The Harlem Renaissance Party (1988), she highlights the roles that Black Americans have played in the history of New York. This story quilt also depicts a gathering of Black luminaries sitting around a dining table, but there is space at the table where the viewer can join the party. The New York in Ringgold’s art is a special space, a liminal space, and when you visit it, you feel like “you’re flying among the stars.”[7]

[1] Faith Ringgold, Tar Beach, Afterword (New York: Scholastic, 1991), 26.

[2] Zoé Whitley, “Summoning Ancestors, Inspiring Descendants: Faith Ringgold and Literature”, in Faith Ringgold: American People, ed. Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayri (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2022), 146-47.

[3] Ringgold, Tar Beach, 5.

[4] Ibid., 21

[5] Bruno Bettelheim, The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977), 126.

[6] Ringgold, Tar Beach, 24.

[7] Ringgold, Tar Beach, 24.