Returning author Elaine Birnbaum is a third-year at Northeastern University studying Media Arts with a concentration in animation and Spanish.

In Fall of 2021, there was a two-week period where Glenstone’s exhibitions of work by Arthur Jafa and Faith Ringgold overlapped. The exhibits were housed in two different buildings located on opposite ends of the Glenstone campus, a ten-minute walk apart: the Jafa exhibit in a huge, spacious room where a video played on the back wall, versus the Ringgold exhibit, which consisted of multiple rooms that went through her entire career. Though born generations apart — Ringgold in 1930 and Jafa in 1960 — both artists engage with the fight of the Civil Rights Movement with the same passion for their community and desire for change. Ringgold herself participated in the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements and used her art to demand change. Jafa, born too late to have consciously experienced and maneuvered through the Civil Rights era himself, uses his art to document what is history to him. Their individual perspectives show through in their choice of mediums: Jafa primarily uses videos and photos to reflect on the past while Ringgold puts paint to canvas to tell people what they aren’t seeing.

The focal point of Jafa’s exhibit was the full-length film akingdoncomethas (2018), a collection of original and found footage, all sourced from the Internet, focusing on bishops giving sermons and preaching the gospel. Some are older videos, specifically from the Civil Rights Movement, while others are more recent. However, they all share the message that better days will come through faith. The singers and congregants pray and hope for a better life. In an interview with Glenstone, Jafa says that “power, alienation, beauty” are what define Black music. He also noted that what he was showing in his film was real art: “the performers.” The first clip of the film illustrates Jafa’s point with Al Green performing his song Help Me. It is a live performance, but the grainy footage mutes the colors. Green stands in front of a dark red background wearing a brighter yellow-green shirt with a grey vest. Despite red being a warmer color and typically showcased in the foreground, here it fades into the background and helps to center Green on camera.

Arthur Jafa

akingdoncomethas, 2018

Video Still

© Arthur Jafa

Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery

Green performs the song with passion and the same devotion one would find in a religious sermon. At the beginning of the song, he sings “If you’re broken down/Jesus is waiting,” encouraging his audience to seek help and guidance from Jesus just as he did. Further on in the performance, he sings “Love is the only medication” and “Love is the only salvation.” Love, as emphasized through Jesus’ teachings, is the only way he and his community sees to escape the suffering of everyday life. The audience feels his love and suffering with him, too; throughout his performance, the words “amen, amen” are heard from audience members. This is what gives Green the power Jafa talks about; his faith in something larger than himself, trust that his suffering will be rewarded, and his ability to preach to others and help them find salvation. The beauty here is his ability to see this suffering and alienation of himself and his community and still say there is hope.

In creating this film, Jafa becomes a curator of sorts, choosing the videos to show and the order in which they are watched. He chose to start off the video with Al Green’s performance, to include sermons alongside gospel, and to include a clip from the 2017 California wildfires and set it to more gospel music. In one way Jafa acts as a historian, showing his viewers the impact of faith on the Black community. In another, he is the artist, expressing the message he believes to be the most prevalent.

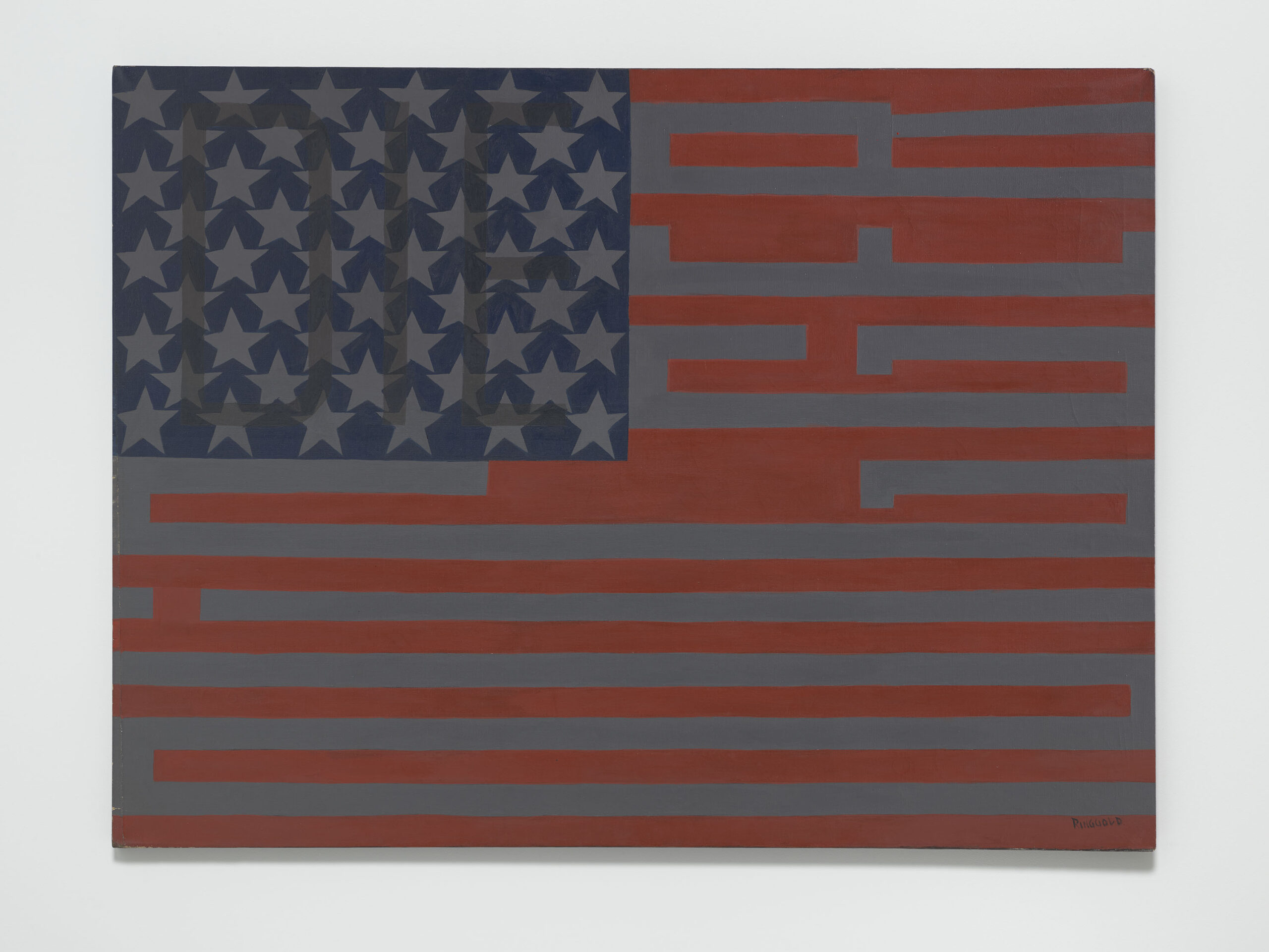

Faith Ringgold

Black Light Series #10: Flag for the Moon, 1969

oil on canvas

36 x 48 inches (91 x 122 cm)

© Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York

Photo: Ron Amstutz

Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland

While Jafa hopes for a better life, Ringgold acts on it. Her constant activism in her everyday life is also reflected her art, such as in the piece Black Light Series #10: Flag for the Moon (1969), a poignant reimagining of the American flag. Part of her Black Light Series, a stop on her quest to explore what it means to paint with a so-called Black aesthetic, the tenth painting in the series was inspired by what she saw as the willful ignorance and hypocrisy of the US government during the 1960s. Ringgold says she was frustrated by the “United States government … spending billions of dollars racing the Soviets to put a man on the moon” while “[p]eople were rioting” and dying for “basic human rights.” Instead of the iconic white stars and stripes, Ringgold uses a dark grey. While the avoidance of white in her palette stands in for a closer connection to the Black community, the uneven stripes and colors also represent how America failed the Black community at the time. It brings a dark and somber mood to the hopeful meaning of the original flag. On top of the stars, she has hidden the word “DIE,” suggesting how she sees the society she lives in as inherently violent and toxic.

Unlike Jafa, Ringgold presents her subjects through the expressive lens of her own experience. She creates her own unique characters to express her unique vision and ensure that everyone can see how she and her community are suffering. With painting, and later on fabric such as in The Feminist Series (1967-72), Ringgold uses a traditional medium to fight for a different interpretation of traditional ideas, one that says everyone is equal regardless of their skin color. Her earliest use of fabric, Ringgold employed her mother, Willi Posley, to create the fabric borders of the paintings. She was inspired by Tibetan tankas, intricate watercolors painted on cotton or silk that could easily be rolled up and stored. In each piece, she employs painted text, a technique she used throughout her career. In Feminist Series #12: We Meet the Monster (1972), Ringgold takes a quote from Clarissa Lawrence, a nineteenth-century feminist icon, who spoke at an anti-slavery conference in 1838. The words themselves are also written top to bottom rather than left to right, which is characteristic of many East Asian languages. With English, however, it makes it very hard to read, letting the words blend more into the piece instead of sticking out, especially as she uses the gold of the fabric for the text. Across the dark blue sky, her words appear: “[w]e want light; we ask it; and it is denied us.” This directly ties to Ringgold’s Black Light Series; she was asking for rights, but in return she was given a man landing on the moon.

Ringgold’s paintings are fairly critical and pessimistic, conveying the anger she felt as she saw her community suffer. Jafa’s videos are much more optimistic and passionate, holding a unique connection to faith and a higher power. These two artists grew up in different generations, surrounded by different and changing societies. Yet both portray the beauty that has come out of such suffering unique to the American Black community. Ringgold creates beautiful works with long-lasting messages, detailing the struggle and pain of wanting basic rights and being denied. Jafa sees the struggle Ringgold paints and shows how Black people have continued to surpass it and come out stronger. In such changing times, it is important to look back and see how far we have come, and to learn the history of such struggles. Looking at Jafa and Ringgold’s works together, I can think of no better way to do so.

Sources:

Glenstone Museum, “Faith Ringgold at Glenstone.” September 1, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-pRI5_DNIs&list=PLwo4tip9KzSLO8p-XELXI8TOwrGa9N8E2

Glenstone, Black Light (1967-69) and Political Posters. 2021. https://www.glenstone.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Black-Light-1967-1969-and-Political-Imposters_FINAL.pdf

Glenstone, Feminist Series, Slave Rape, and Soft Sculpture (1972 – 1981). https://www.glenstone.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Feminist-Series-Slave-Rape-and-Soft-Sculpture-1972-1981_FINAL.pdf

Glenstone Museum, “Arthur Jafa at Glenstone Museum.” December 5, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3YIeRljQ3s