Asiya Rizvi is a fifth-year student at Northeastern University studying computer science and graphic design. She is interested in the marriage between technology, art, design, and human relationships.

“I am concerned with meaning, playing on the edge of it, finding an edge that is close to oblivion and can be transformative.” Leslie Thornton [i]

Through her distortive style, film and video artist Leslie Thornton’s exhibition Begin Again, Again examines the relationships of power between humans and technology, and their combined capabilities for annihilation. The exhibition, on view at MIT’s List Visual Arts Center from October 22, 2021 – February 13, 2022, features time-based media work that narrates events and experiences spanning from the post war period to today. The subject and location are especially noteworthy considering MIT’s history and affiliation with nuclear weapon development and the Manhattan Project. At least ten MIT faculty members worked on the Manhattan Project, and in this context, Thornton’s work reads as both didactic and extremely relevant in relation to MIT’s efforts to encourage learning and growth from its controversial past. Using footage that is heavily manipulated and edited, the exhibition insightfully addresses the relevant themes concerning our increasingly interconnected and potentially exploitative relationship with technology, and successfully encourages viewers to confront the muddled and often dismaying memories and considerations surrounding related events.

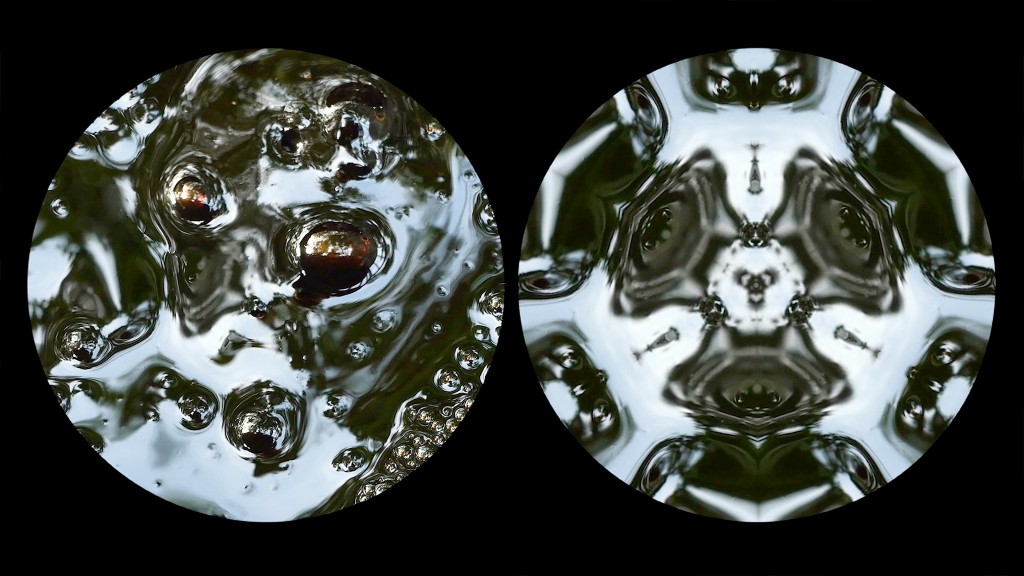

Begin Again, Again is arranged in three rooms, with overlapping sounds providing an interesting conversation between different pieces of work and contributing to the overall distortion effect. The pieces are durational, and with some of the longer videos, it is impossible to view the entire experience in one visit, which can initially feel like a dilution of the overall message. However, in a Frieze interview from 2018, the artist remarks: “I use the term ambient to refer to a viewing environment in which the viewer is in charge of the time.”[ii] By allowing viewers some control over which snippets they see and hear, Thornton opens the possibility of oblivion and transformation of meaning, in a way that is reminiscent of video sculptor Shigeko Kubota’s work. In Gloria Sutton’s essay on Kubota titled A Matter of Memory: Shigeko Kubota’s Video Sculptures, Sutton describes one of Kubota’s pieces that contains multiple monitors as a “video collage,” which is a term I would apply to Thornton’s work as well.[iii] Like Kubota, Thornton plays on the abstraction and distortion of the individual videos as they overlap one another and make it impossible for the viewer to follow a continuous narrative. Visual and audio components of Thornton’s videos include jarring images of melting tar, chaotic ant colonies, anxious voices, recounts of bodies after the bombing of Hiroshima, and the imagined, post-apocalyptic ruins of the world. These components unify to encapsulate the sentiments regarding events of mass destruction in a way that, in my opinion, is likely true to the incomprehensible and staggering nature of such events.

Episodes and clips from the black-and-white full-length film Peggy and Fred in Hell (1985) occupy the second room in the exhibition. Created over the span of about thirty years, Peggy and Fred in Hell is broken into episodes, a selection of which are displayed in the exhibition with a total run-time of 176 minutes. The longest episode, titled Peggy and Fred in Hell: Folding (1983 – 2015), is displayed front and center on a large projector with other clips playing on smaller monitors around the room. The videos themselves are collages of scenes from a post-apocalyptic, anarchic environment overrun by AI in which only two children exist. This narrative is a means for the artist to comment on viewership through technology as it relates to surveillance. Thornton represents an AI watching Peggy and Fred in an initially voyeuristic, then increasingly interactive manner as the children become aware that they are being watched and begin to “perform.” The artist has commented on the ability for science fiction and ethnography to “address a problem of needing a place to play out speculation, because in one’s close and real proximities, such-things-would-not-happen.”[iv]

Video as a medium is an excellent tool for portraying and carrying out speculation, exemplified by the alternative, futuristic world of Peggy and Fred in Hell. Viewers become witnesses to a world they would otherwise never encounter; one that is black-and-white, cluttered by the debris of familiar objects and sounds, and not only speculative of the post-apocalypse, but theoretically possible (and believed by some to be likely, exemplified here). By conceptualizing the aftereffects of mass destruction, Peggy and Fred in Hell forces the viewer to consider the world we may ultimately “leave behind” or pass on to future generations. It is intriguing to explore such a landscape through the imaginative, inventive lens of children who can still dance, sing, and play in the ruins of the world. After viewing scenes from Peggy and Fred in Hell, the future begins to feel simultaneously despondent and, with children as the initial subjects, hopeful for renewal in spaces that have become void of most life.

The third room in the exhibition features Cut from Liquid to Snake (2018), which comments on the ineffability of mass annihilation, the weapons that cause it, and both the responsibility of and effect on people. The twenty-six-minute film includes clear excerpts of people recounting events such as the Manhattan Project and the aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima, but also clips during which speech and images are cut, re-arranged, and generally warped. Abstract and moving images mimic the aftereffects of atomic weapons on the landscape on which they have been used. Here, the distortion seems to represent the inability to put words or thoughts to events of mass destruction. Through snippets of dialogue – a hesitant and seemingly fearful voice saying, for example, “if anything happens, there will be this record of my last few moments”– the video additionally encapsulates the secretive and almost taboo nature of discussions surrounding developments of weapons of war. A family member of the artist recounts the relationship between the artist’s father and grandfather, who spent a period of time working on the Manhattan Project unbeknownst to each other.

Similar to the choice to feature this exhibition at MIT, Thornton’s subject matter is compelling and intentional in the context of her familial ties to the destruction her work represents. In fact, it was supposedly the artist’s father who screwed in the last bolt on the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. I wonder if, to an extent, her work is a form of taking accountability or addressing the role her relatives played in these events. Whether her art serves as absolution is rather subjective. However, the sentiments of those affected by mass destruction are uniquely conveyed and become didactic regarding the weapons and decisions resulting in such events, encouraging us to make more informed choices in the future.

The durational quality of Leslie Thornton’s work as well as the discombobulated nature of the exhibition intentionally make it difficult to form a clear analysis. Viewers of the exhibition leave with a potentially disjointed collection of ideas, images, and sounds relating to power, technology, destruction, spectatorship, and accountability. In the artist’s own words, her work “has echoes and puns and a kind of poetic rhetoric of condensed, suggestive work that the viewer has to expand.”[v] Thornton places most experiential decisions regarding her work in the hands of viewers. Uniquely open-ended and abstract, her work not only encourages but even leaves viewers no choice but to take the conversation further and make their own conclusions. Viewers of this exhibition must also make choices regarding how they would like to experience the work in relation to order and duration. In this way, Thornton perspicaciously captures the fragmented thought process of both experiencing and speculating the unimaginable. Faced with self-erasure, viewers of Begin Again, Again are prompted to contemplate breaking or embracing the cycle of human destruction and rebirth in conjunction with technology.

[i] Kidner, Dan, Leslie Thornton’s 35 Years of Radical Filmmaking (London, United Kingdom: Frieze Interviews, Aug, 2018), https://www.frieze.com/article/leslie-thorntons-35-years-radical-filmmaking

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Sutton, Gloria, A Matter of Memory: Shigeko Kubota’s Video Sculptures, (New York, NY: MoMA, Sep 2021), https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/627

[iv] Halter, Ed, Hell is For Children (Close-up, September, 2012), https://www.artforum.com/print/201207/ed-halter-on-leslie-thornton-s-peggy-and-fred-in-hell-31962

[v] Molina, Feliz Lucia, Leslie Thornton by Feliz Lucia Molina (Bomb, Oct, 2012), https://bombmagazine.org/articles/leslie-thornton/