This week’s contributing writer, Jessica Scott, is a 3rd year MFA candidate in Studio Arts at the University of Massachusetts Amherst where her research and multidisciplinary art practice focuses on feminisms, bodily autonomy, imaginative ecologies and public history.

In early Fall 2019, my co-curator Jill Hughes and I decided to show the artists’ book Artifacts at the End of a Decade for our 2021 University Museum of Contemporary Art (UMCA) Curatorial Fellow Exhibition. We’d only seen Artifacts’ “pages” through the thumbnail images on the 5 Colleges Museum’s Digital Database but we were piqued by how much it stood out from the collection’s 3000 works on paper. Published in 1981 by Steven Watson and Carol Venezia-Huebner, Artifacts at the End of a Decade is an unbound artists’ book consisting of 44 unique pieces of photography, ceramics, fiber, print, clothing, painting, and drawing by artists including Martha Rosler, Fab 5 Freddy, Laurie Anderson, Sol LeWitt, Lucinda Childs, and Robert Kushner, among many others. As a multidisciplinary American survey of the 1970’s in the form of an artists’ archive, Artifacts is both a response to its time and far ahead of it.

Artifacts in its portfolio. Photography by Stephen Petergorsky.

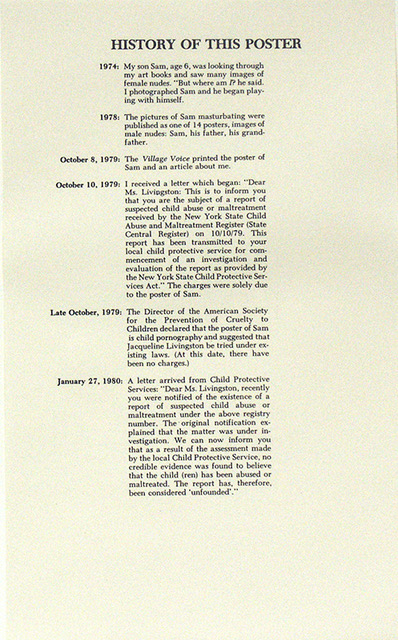

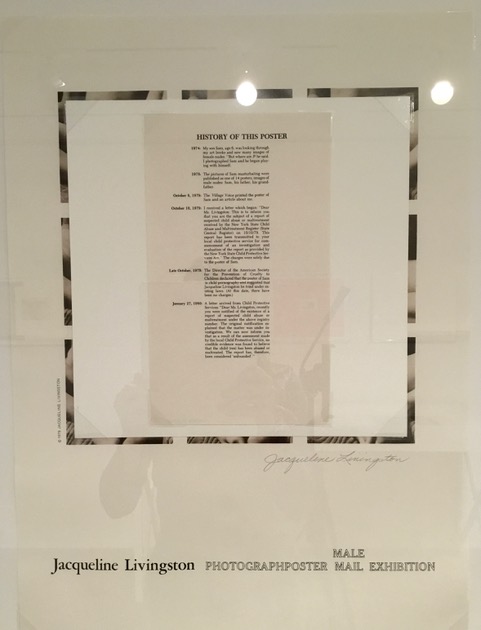

While leafing through the portfolio at the UMCA archives, we examined a piece called PhotographPoster Male/Mail by the artist Jacqueline Livingston. In the portfolio, her work is accompanied by a poster which hadn’t appeared in the digital collection. The poster named the subject of her tiled nude photographs as her 6-year-old son and explained the casual circumstances in which they were taken. The images are cropped to portray a nude male figure with his penis in his hands, but each photo cuts off at the torso obscuring the age and identity of the subject. The poster details, in chronological order, some of the immediate consequences Livingston suffered after publishing these photos of her child in 1978. Compelled to do my own research, I discovered that the public backlash to these photos would have a lifelong impact for Livingston.

The poster from Jacqueline Livingston’s PhotographPoster Male/Mail. Photography by Stephen Petergorsky.

After the publication of PhotographPoster Male/Mail, Livingston became a target of the new child pornography legislation that took effect in the US in the late 1970s. New York Child Protection Services threatened to remove her son from her care citing the photos as evidence of abuse. Livingston lost her job as a professor of photography at Cornell University, several art magazines refused to run ads for her, and some of her films were confiscated by the Kodak Film Company. In 1982 she attempted to change professions, opening One-Artist’s Gallery, but due to continuing FBI surveillance she was forced to close.

In a recent interview, Steven Watson and Carol Huebner-Venezia state that they were never the targets of any public outcry for distributing this work as a part of Artifacts’ collection[1]. The severity of the backlash that Livingston alone experienced stunned me, prompting a realization of the responsibility Jill and I had as curators to carefully consider our own community’s standards for displaying such content. But more than that, I was gripped by the familiarity of this story, a recitation which continues to echo in our public imagination when we talk of mothers who are artists and take pictures of their children.

Jacqueline Livingston was one of the first victims of an increasingly polarized attitude towards contemporary art, one which would gain momentum by the 1990s and become part of what was known as the Culture Wars, climaxing in protests against artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe and Chris Ofili as purveyors of dangerous obscenities. Other female photographers including Claire Henze, Nan Goldin, and Sally Mann were also taking nude pictures of the children in their lives, and, like Livingston, they faced a distinct brand of vitriol that attacked their reputations, their art, and the very structure of their families. While the style and degree of nudity depicted vary strongly between photos by Livingston, Henze, and Mann, the fact that they are all the subjects’ mothers seems central to the broad accusations of child endangerment they each received. Some of the public reaction was a rejection of how these artists radically collapsed and combined categories, pushing back against a cultural expectation that women’s professional, artistic, and intellectual lives be maintained separately from our lives as mothers. Amidst these questions, Jill and I were most concerned with how to curate and contextualize Livingston’s work so that it could receive a fairer reception from the audience for our upcoming exhibit.

It has been 40 years since Livingston’s PhotographPoster Male/Mail was originally published in Artifacts at the End of a Decade. She died in 2013 and her son is grown. Many of the children in these pictures have gone on record to say they are fine and the pictures themselves did no harm[2]. We, the public, have also changed: our social media is full young influencers giving the world unprecedented access to their youthful routines in exchange for ad revenue and reality tv shows regularly feature child stars competing with the stylized composure of adults. We protest and consume, in equal amounts, hypersexualized media featuring children, media which paradoxically warns against the outcomes of this hypersexualization at the same time as it peddles it. Meanwhile, the mainstreaming of conspiracy theories about sexual predators like Pizzagate[3] creates a sensationalized threat of fictional child abuse, undercutting the solid documentation of a national regime of blatant child abuse in detainment camps at the Mexican-US border and carceral facilities coast to coast. With cultural discourse pulling even farther away toward each contradictory extreme of the issue, how could we predict the possible consequences of exhibiting PhotographPoster Male/Mail work at a teaching museum on a public university campus?

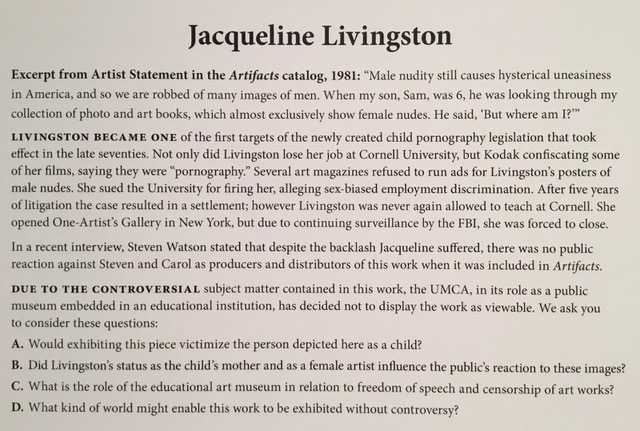

With the full support of the UMCA leadership, we have chosen to exhibit Livingston’s piece alongside the rest of Artifacts’ collection because it is critical for us to be authentic in our claim to offer Artifacts in its entirety. Each piece contributes to the intertextuality of the portfolio that marks it as a singularly complex, layered, and special work within the UMCA collection. But we have chosen to display PhotographPoster Male/Mail in such a way that the explicit portions of it are not viewable, and included the poster detailing the public backlash in the frame with the work. An extensive wall label below describes our curatorial concerns and the process of arriving at this solution for display. At the end of a committed conversation with UMCA leadership, we could not deny the very real possibility that controversy about this one piece could overshadow the entire show at a loss to everyone involved: curator, museum, and audience alike.

Our display solution for Livingston’s work from the UMCA exhibit. Photography by Stephen Petergorsky.

Our display solution for Livingston’s work from the UMCA exhibit. Photography by Stephen Petergorsky.

Instead of interrogating Livingston or her motives as a mother and artist, what does partially concealing PhotographPoster Male/Mail do to us, the viewers? The history of this embattled discourse on images of children forces the viewer to temporarily inhabit the mind of a predator to determine if this work could be seen as titillating instead of viewing it as the artwork intended. Our censorship of these artworks is a trap for kids, their parents, the audience, artists, and for people in social services on the frontlines of actual incidents of child abuse because it makes us see something that isn’t there and erases what actually is there. We search these images for signs of danger first, eliding other possible meanings, artistic value, and insight, while ignoring, tolerating, or actively abetting cruelty towards children in our national policy at the border and in America’s war on the poor. Jill and I could not determine the perfect way to show this work because the public is still gripped in a confounding political impasse about which children deserve safety, what threats are real and which are propaganda. Even though the decision is made and the work is hung, I continue to turn our treatment of Jacqueline Livingston over in my mind. The final question we ask the viewer in the wall label under PhotographPoster Male/Mail is most poignant for me: what kind of world might enable this work to be exhibited without controversy?

The exhibit of Artifacts at the End of a Decade is open at the University of Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, until December 2021. Visit Artifacts at the End of a Decade Digital Exhibit for more information.

[1] Interview with Steven Watson and Carol Venezia-Huebner, February 2019.

[2] “It was actually Sally Mann’s children who insisted that she publish the photos sooner rather than later; she had wanted to wait a decade, when “the kids (wouldn’t) be living in the same bodies.” Mann and her husband did take steps to protect their kids—the two older children went to a psychologist to be sure that they understood the implications of publishing the photos. She also attempted to limit the availability of Immediate Family in Lexington-area bookstores and libraries.” https://www.eileenmcginnis.com/blog/2019/4/29/exposures-photographer-sally-mann-and-the-dangerous-art-of-motherhood

From Livingston’s blog, “With this assurance, my then eleven-year-old son and I met with a social worker who questioned us with our lawyer present. My son was asked how he felt about the photographs of him (“Fine we’re nudist.”), and I was asked, “Are you photographing other children nude?” (“No.”) The social worker had seen my fourteen posters in the local gallery in a feminist bookstore and said he supported my work.” http://jacquelinelivingston.blogspot.com

[3] https://www.politifact.com/article/2016/dec/05/how-pizzagate-went-fake-news-real-problem-dc-busin/

Additional Sources:

Jenkins, Tiffany. “Art of Abuse”, The Independent, September 2010. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/art-or-abuse-a-lament-for-lost-innocence-2078397.html

Linkhof, Ralph and Parsons, Ralph. “The Controversial Act of Taking Pictures of Children”, UNFRAMED, LACMA Blog. December 2012. httpsChildren” ://lacma.wordpress.com/2012/10/11/the-controversial-act-of-taking-pictures-of-children/

Reich, William. “Jacqueline Livingston: Male Nudity Against The System”, Artlark.org, June 2020. https://artlark.org/2020/06/21/jacqueline-livingston-male-nudity-against-the-system/

Steward, James Christen. Michigan quarterly review,” The Camera of Sally Mann and the Spaces of Childhood” Volume XXXIX, Issue 2: Secret Spaces of Childhood (Part 1), Spring 2000