This week’s contributing author, Aisha Samake, is a third year Game Art and Animation student at Northeastern University.

VoCA is pleased to present this blog post in conjunction with Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History, Gloria Sutton’s Fall 2020 Art History Course: Disruptive Image Technologies at Northeastern University. This interdisciplinary course examines how the distribution, circulation, storage and retrieval of still and moving images have shaped the understanding of contemporary art.

In the live Q&A hosted by the Museum of Modern Art on June 18th, 2020, artist, activist, and author Faith Ringgold told Anne Umland, Senior Curator of Paintings and Sculpture, that “American society keeps repeating itself.”[1] Given that Ringgold has an array of artworks that correlates with the social scenes of today, this statement resonated with me. For example, in 1967, Ringgold created American People Series #20: Die, a painting that was a direct representation of her experience as an African American woman living in the United States. The painting depicts well-dressed people of all races and ages partaking in a spontaneous street riot. Ringgold, feeling like such serious issues were happening around her but being ignored by the media, used her artistic agency to tell the story. Flash forward to the year 2020, where people of all races, genders, and ages take to the streets in support of important movements like Black Lives Matter, and other social groups.

As an African American myself, I greatly connected with Ringgold’s artworks, as well as her words about her life, the importance of her art, and art in general. I am also an artist who wants to tell my story about the world around me, and Ringgold does just that. During the conversation with Umland, Ringgold effectively stated how “important it is to be inspired by the times we currently are living in.” Looking to the world around you is a great starting point for creating art, though so is looking to the past. Intergenerational conversations like the one between Ringgold and Umland are vital, as one person’s experience can help shed light on what other people may be dealing with. By sharing one’s story, history is illuminated, archived, and developed. Umland described the “important role that Ringgold’s many exceptionally [diverse works] have played in disseminating her art and ideas beyond the museum’s walls.” Ringgold’s popular painting Die, which is in MoMA’s permanent collection, is a prime example.

Faith Ringgold’s Die (1967) was inspired by Picasso’s Guernica (1937), a work that she and her two daughters viewed periodically when it was on view at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Guernica is a large political painting that depicts the tragedies that occurred during the Spanish Civil War. It is painted with grays, whites, and muted tones and shows people and animals in anguish set against the dark background. Similarly, in Die, there are people scattered across the canvas, their variations of white and black, or orange or pink clothing stand out vividly against the dark grey checkered pattern background. Just like in Guernica, the people’s faces are full of distress. One person holds a knife while another points a gun right in the face of a woman. Blood stains cover their clothes and drip down to the ground. Two children of different races sit near the center of the canvas with tears streaming down their faces. One man appears to be choking another character. Ringgold said she wanted to “give visual form to things left out of the news at the time.” When she made Die, due to the politically charged subject matter, no museum was willing to accept it; it took fifty years since its creation for MoMA to acquire it, and now it is one of the most viewed pieces in the Museum’s collection.[2]

Art, as stated by Ringgold, is a powerful means of expression. Growing up in Harlem, New York, she faced segregation, racism, sexism, and discrimination. Another painting that especially embodies many of these struggles is called American People Series #14: Portrait of an American Youth (1964), which depicts Ringgold’s brother, Andrew. “My brother is the perfect symbol for the difficulty [of the times back then],” Ringgold said. “He wanted to do more things than what was allowed for him to do because he was a young black man.” In the painting, Ringgold represents what was problematic for her brother when he was growing up: arrows pointing downwards indicate his life going negatively and away from himself; a red stop sign signifies the stopping of life opportunities he could have had. There is also a large white man silhouetted behind him showing the different positions of power, all set against a vibrant red, white, and blue background that calls forth the colors of the American flag.

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #14: Portrait of an American Youth, 1964, oil on canvas, 36 x 24 in.

Looking at this painting and knowing how historically black men were treated unfairly and weren’t giving the same opportunities as others, one can’t help but think of black men like George Floyd, Trayvon Martin, and so many others whose lives were taken too soon. Ringgold mentioned how the world was very severe during the 1960’s, and she and I believe there is still a lot of social and political change to be done now, and the use of art can help steer the path to social change. Intricate murals of George Floyd and other lives lost cover walls in major cities as Black Lives Matter protests take place. Posters with powerful symbols are being carried through the streets. People today have the agency to demand change in a way that was much harder to do in the 1960s.

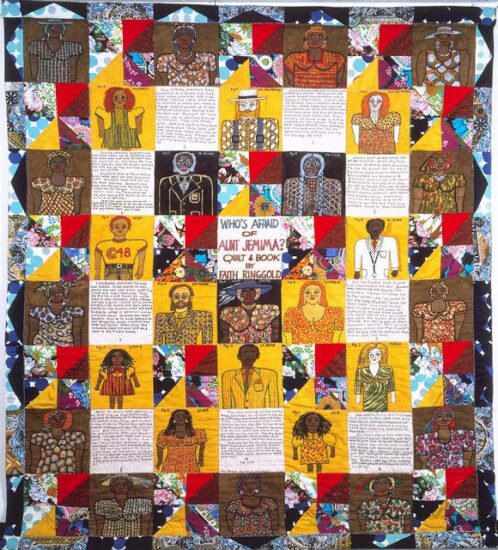

Faith Ringgold, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?, 1983, Acrylic on canvas, dyed, painted and pieced fabric, 90 x 80 in.

In addition to making paintings, Ringgold has also written children’s books and created story quilts, including one featuring the popular caricature Aunt Jemima, an iconic American symbol synonymous with breakfast items. In Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983), Ringgold exposed and subverted the racist undertones in the way Aunt Jemima is depicted as the mammy stereotype that was often used to portray African American women by giving her a story; she was shown with a family and had hopes and dreams. Ringgold states that Aunt Jemima is a “powerful woman”, not something to be ridiculed or stereotyped. Ringgold decided to give black people a voice. Black women often struggle to be in positions of power and are often reduced to the maid or service stereotype, unable to hold their own in life. Ringgold flipped that ideology and instead showed a successful woman who is content with her family. This past summer, the company that created Aunt Jemima, Quaker Oats, decided to change the brand and image to something less belittling; the change took time, but progress is happening. “Black people have to give ourselves a lift,” Ringgold said in the Q&A. She saw Aunt Jemima, a derogatory character, and decided to make it into something more positive that black people could look to and aspire to be.

Faith Ringgold’s art holds power because of how it connects to the world of the past and the world of now. “You scratch the surface of any work by Faith Ringgold and you will find social commentary,” Umland remarked. I agree with that statement and how it connects with bridging the past to the present. History is a continuous spinning wheel, and artists especially need to be aware of the similarities and the possibilities for change. It can greatly impact the future generation for the better.

[1] Faith Ringgold, Anne Umland, “Faith Ringgold | Live Q&A | VIRTUAL VIEWS,” YouTube video, MoMA, June 18, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ko5pr8SzgtE

[2] According to Ronnie Heyman, the president of MoMA’s Board of Trustees, during the live Q&A hosted by the Museum of Modern Art on June 18, 2020