This week’s contributing author, Jennifer Ribeiro, is a 4th year Computer Science student at Northeastern University with an interest in art and film.

VoCA is pleased to present this blog post in conjunction with Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History, Gloria Sutton’s Fall 2020 Art History Course: Disruptive Image Technologies at Northeastern University. This interdisciplinary course examines how the distribution, circulation, storage and retrieval of still and moving images have shaped the understanding of contemporary art.

Launched amidst Boston’s COVID-19 shutdown in March 2020, Shelter in Place (SIP) is a non-commercial gallery that showcases 1:12 scale exhibitions in a miniature space in the creator’s apartment. Despite that the gallery’s name indicates a stagnant command, the project capitalizes on added limitations in order to introduce new potentialities in the realm of displaying and understanding art. The hope is to make art more accessible when both space and money are limited. The project began with Eben Haines and Delaney Dameron, two Boston locals, and expanded during COVID to help other artists. In their small-scale exhibit room, which is rendered at a scale of 1 inch to 1 foot, they install local artists’ works for 3-4 days and photograph them for their website and Instagram. Although the work is miniature, the photographs make the space appear full scale, enabling grand ideas to be executed at a much smaller budget. SIP is a direct example of how contemporary artists are adapting to the world’s shifting states by creating new avenues for art production.

As a result of the gallery space’s layout and small size, SIP provides a platform both for artists who may lack the resources needed to execute large-scale ideas and for viewers who may be unable to visit galleries in-person, thus making the entire gallery experience more accessible for all parties. The execution of the small-scale objects and photographs make viewers contemplate the relationship between space and feeling; any individual viewing work within SIP will be aware of the element of scale and consider how it can add a degree of intimacy to the experience, despite not having a physical body within the gallery. As Haines describes in the interview below, recognizing the size of the environment allows viewers to examine the process and placement more closely and understand the intentionality with which every object is placed. In a world of increasing digital presentations, SIP’s approach differs from virtual reality projects in its effective simulation of real-life spaces. Where VR and AR-based projects embrace the expansive possibilities of digital environments, the process of SIP prioritizes recreating lifelike experiences and the added uniqueness of handmade, miniature realms. Overall, SIP brings into question our perception of ourselves, our world, and the scale we put onto physical objects.

Although SIP uses miniatures as a response to the pandemic, miniatures have a long history in the art world. In 1930, Narcissa Thorne assembled a group of artisans to create the Thorne Rooms, a 1:12 scale series of intricate interiors. The original purpose was to give the public insight to what rooms looked like during different time periods, part of a wave of efforts to conserve American history, produced by a feeling of nostalgia for simpler times. Another well-known miniature artist is Thomas Demand, who gained traction in the 1990s. Unlike Thorne, he sculpts politically charged spaces such as a ballot room, the oval office, and the kitchen hideout of Saddam Hussien; familiar spaces that are always vacant of people,

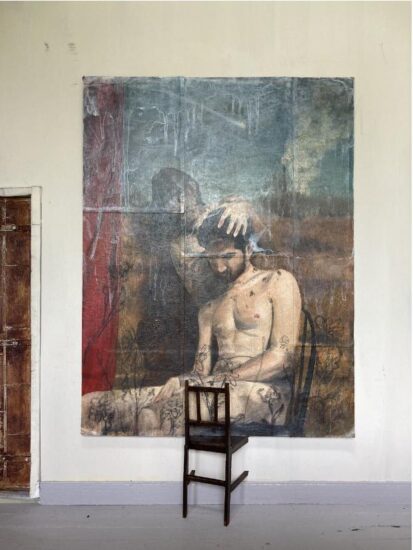

The following is an interview with Eben Haines about the gallery as a whole and an exhibition of his own work that was shown at SIP. Haines is a Boston based artist whose exhibit highlights themes of death, renewal, and the ever-changing global landscape.

Is SIP your first experience installing and curating a gallery or do you have previous experience in life-sized gallery installations?

I work in the Exhibition Design department at the Museum of Fine Arts, so I have experience being around installs and with how that whole process works, which is why I try to acknowledge all that invisible labor as part of our own exhibitions. But aside from my own work, I don’t have much experience with curating or hanging shows myself. The scale makes install happen a lot faster and without crew, lifts, and gantries, but for all intents and purposes the gallery appears life-size so I think the importance of pacing, visual relationships, and context within an exhibition are the same.

What place do you think virtual exhibits have in the art world?

I think right now especially, virtual exhibits are pretty important to us getting through the pandemic. Of course, there are successful versions and unsuccessful ones, but I think that the way we view art is undergoing a temporary change that will have lasting effects. There is less room for discovery online, and so artists have to be more blunt in their presentation. Rather than [seeing this as] an obstacle, I think a lot of artists are using this complication to their advantage by making work that loudly says what it means, forgoing the usual “art is what you make of it” and creating with specificity. I think that when it becomes more reliably possible to view new work in person, we’ll see how refreshing it is to be able to discover things without someone directly pointing to it, but also how refreshing it is that many works have a more concrete message.

How did you approach making your exhibit/curating it?

My show was made up of a lot of apparati that I’d envisioned for the past few years that I never had the money, space, or time to create at full scale. I already had some ideas about imagery, pertaining to the pandemic and the gaping holes capitalism leaves in the wellbeing of most Americans the crisis has writ large. (For your own context, my work has been about the failures of capitalism and the exploitation of the working class for a long time before COVID, but the pandemic has become a relatable representation of it). Because I’ve never had the room to make sculpture at scale, I wanted to use this opportunity to make the 3D work that I’ve been sketching for a long time. I’m a painter whose favorite artists are mostly sculptors, so it was really great to be able to delve into that.

What is your documentation process? Thomas Demand would set up the camera first and then build his model around it. Is this similar to your approach?

You’ll notice that we never show the fourth wall of the gallery, because that is where we take the pictures. So the documentation process is pretty simple, just an iphone on a little kickstand and a giant hole in the wall.

How do you think the scale affects the perception of the gallery?

I think that when folks realize it is a miniature space, they stop and look more closely. Everything is placed where it is with purpose, and therefore is part of the image and not just random detritus. It also seems that this miniaturization of what many would consider “hard art” makes it suddenly much more manageable. To be able to experience something massive while knowing it’s about the size of your hand means that the ideas behind the work are also within reach, and not relegated to those with an art history degree and a lifetime in the arts. It is this shared use of imagination that allows for a lot more possibilities mentally than a lot of physical spaces might allow for. That, or people just love how cute it is.

I noticed that you have miniature packing materials. Does the work come like that or do you add them in? Either way I love it.

Sometimes we add in these materials, but a lot of the time people will send in their work with miniature crates and packing materials. A few have mentioned that making crates, especially when we were in lockdown, was a way to make this miniature show feel like a full-sized one. For a lot of artists, packing the art is a way to finalize the job of creating, before the separate exhibition/critique/sale phase, and so making miniature crates is a way to normalize that process.

Do you curate the other artists’ works or do they give you a plan on how to set it up?

We generally ask for a plan, because one of our objectives for these shows is to create a fully immersive installation, as opposed to just works on the walls. When artists send us a proposal, we’re looking for works that think about and utilize the whole space, and so the placement of works is very important. But because artists are working off photos and elevation drawings, a lot of the time we will go back and forth looking at images to make sure everything is perfect.

Back in April 2020 you said that you plan to continue the project as long as possible… now that we are well into winter have your plans changed? How do you plan to keep the momentum going?

Since the beginning we decided that we want to continue the gallery as long as it is needed. It doesn’t look like the pandemic is going to end any time soon, and artists are still sending us submissions every day, so it would seem that it still has a valuable place in the art world.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston has acquired the gallery itself, with a promise to continue hosting exhibitions starting in February [2021]. I am in the midst of building a new model, and so we will be “moving” into our new space in December or January. We’re glad that the museum is interested in continuing the project in some way, but we are also keenly aware of the price tag that comes with seeing the gallery in person, not to mention the more static nature of limited rotations planned. We’ve fixed a lot of the mistakes made in building the old space, adding openings to make documentation easier and placing windows to maximize the light we get through the existing windows in our apartment. The original model was never built with a gallery in mind, so we’re excited to see what a more purpose-built object can do!

Thank you to Eben Haines for taking your time to answer all of my questions. To learn more about Shelter In Place, go to https://www.shelterinplacegallery.com/ or Instagram @shelterinplacegallery.