This week’s contributing author, Michelle Jones, works in museums, galleries, and private art collections through curatorship, research, academic outreach, exhibition design, content development, public engagement, and collections management. She has a Master of Arts Degree in Museology majoring in Curatorship and Higher Education and a Bachelor’s Degree in studio art (photography) and the history of art.

As an educator who works with museums and art collections to create access and interdisciplinary learning opportunities for higher education students, the COVID-19 crisis has posed a particular set of challenges. Since March 2020, opportunities to engage in-person with collections across the Bay Area have ceased; class visits to collection spaces and galleries scheduled months in advance were put on hold or canceled across the state of California, leaving educators like myself scrambling to figure out how to make digital access points feel as open and enriching as they would be in art’s physical presence. As I mourned the loss of in-person art-viewing, I was reminded of Alain de Botton’s book Art as Therapy, which tells us how, in times such as this, “art can absolutely lend us hope; it dignifies our sorrow; can expand our horizons; help us understand ourselves [and others]; rebalance us and makes us appreciate the familiar.”[1] Yet how can we simulate this practical way of experiencing art and fostering peer-to-peer dialogue between students when they are unable to do so in person?

Screenshot from Michelle’s current online lecture given to museum studies undergraduate minor students who are creating interdisciplinary tours of museum collections online and offline. Photo credit: Author

Earlier in 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, educators quickly moved their teaching online, adopting Zoom and other digital platforms that provided alternatives to group work and in-person study. But digital art exploration is almost always a solo activity. How do we incorporate peer to peer discourse without being together in the physical presence of art? The loss of interdisciplinary connections experienced during in-person visits is at the top of my mind; in live discussions that take place around a work of art, where students are encouraged to speak amongst each other and apply diverse skills to examine and discuss the art in a more open and less restrictive space than in the traditional classroom setting. As Heidy Geismar of University College London writes,

“Object lessons constitute powerful subjectivities in museums—for instance, forging experience and understandings of ‘the public,’ ‘participation’ and ‘citizenship’…Object lessons are, therefore, both ontological (they tell us something about what there is) and epistemological (they help us interpret and explain what there is).[2]

An example of a traditional in-person, object-based learning experience with students from a fashion and design class at San Francisco State University. Students practice close looking of Egyptian Ushabti made of faience for color theory and material inspiration. Photo credit: Taylor Kinley

Successful methods of digital engagement are not created or adopted overnight. It requires time and resources, and demands even more time for educators to navigate these complex digital collection management systems to develop lesson plans. Online viewing platforms take months to build, but they also require substantial investment in staffing, expertise, money, and can require higher internet connection speeds to work correctly. As so many museums put off these large digitization projects over the last decade claiming lack of funding, many found themselves scrambling at the beginning of the pandemic to provide access to a collection that had shut its doors. Some are still struggling to make their collections digitally accessible, moving into the last quarter of 2020. As Leah Ollman, visual arts writer for the LA Times recently wrote,

“[Online viewing rooms] are immensely useful in providing access to a cosmic encyclopedia of possibility, but each entry is just that, an abbreviated reference, too often taken as a sufficient substitute for the thing itself. The instant consumability of those digital images is what disturbs me most…Our screens serve as windows but also as barriers and dividers. We do indeed see more, but we perceive less.”[3]

How can we, moving forward, make digital experiences work better for the kind of teaching and interdisciplinary exploration we practice? What has been developed or available thus far into 2020 has been largely geared towards younger children, providing family-oriented activities and teachings to supplement online learning, which became a massive responsibility for parents during the first half of the year. However, it is clear that there is an obvious need for digital content that caters to higher learning as well. For instance, university and college students are often curious about how art objects are made, and the act of close looking has always been a large part of my pedagogy. The digitization of collections could enable slow looking and close observation with minimal restriction to the proximity of objects, and can provide a magnified look into the artist’s process, materials, and design. While digital viewing does not replace the experience of physically interacting with objects, these investigations can still happen online, and the group discussions are sometimes more generative, with students having higher confidence in asking questions without peer judgment or being interrupted.

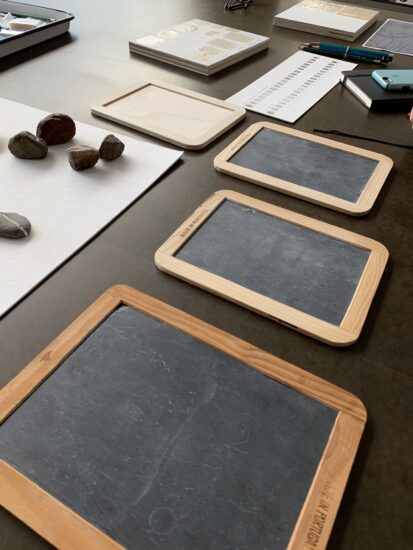

Samples of materials used in object-based learning sessions with university students at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The Vija Celmins workshops for students were held in the conservation lab at the museum. Replicas of Celmins’ work were created so that students could touch them and examine the materials. Photo credit: Author

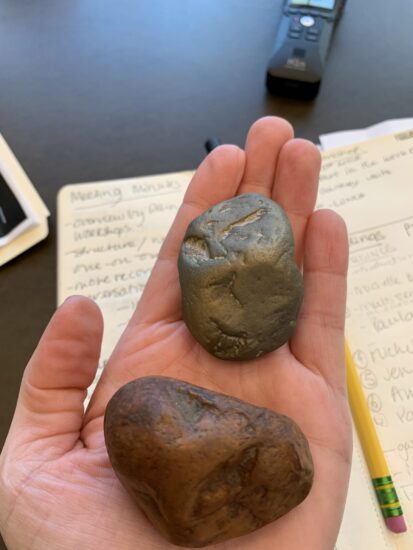

Replica stones were cast by the museum so that students could hold both an original rock (not Vija Celmins’ art) and the cast version of the same rock. Students are able to realize the difference in weight, materials, and detail of the rocks. Photo credit: Author

Despite digital offerings not being able to replace the in-person art experience, there have been many beneficial outcomes as well. In their recently published study called Culture & Community in a Time of Crisis: A Special Edition of Culture Track, La Placa Cohen partnered with Slover Linett Audience Research to survey 124,000 respondents through 653 cultural organizations (25% of those organizations being art museums). Their findings uncovered positive reflections on digital art engagement such as: “I’m disabled, so even COVID-19 aside, I appreciate digital access to cultural explorations I might not otherwise have.”; “I hope this kind of creativity in access and availability grows in non-pandemic times.”; “I was able to participate in activities that I might not be able to afford financially.”; “The rapid shift to online programming and digital exhibits from my favorite institutions across the country has allowed me to participate more and on my own schedule.”[4]

As object-based lessons move to online platforms, the genuinely positive aspect of this shift is that students, educators, and museum professionals are forced to experience art in a way that they never had to previously. Digital engagement in collections has called upon more measures of inclusivity and accessibility for all. It has resulted in empathy for those who embody art in an entirely different way than most viewers. The access to collections by students and educators worldwide has been an enormous achievement of some of the larger museums and collections that were able to produce digital content and activities on a global scale. The access to differently-abled folks has meant that looking at art is not merely about looking anymore. It’s about the entire experience of looking, sensing, and engrossing oneself in a more meaningful and concentrated manner. The sharing of this experience in such a widely-spread forum has connected people for educational purposes and has provided that platform for interdisciplinary discussion that incorporates far more than just one interpretation of art.

[1] “Q+A,” September 30, 2013, https://www.alaindebotton.com/art/q

[2] Geismar, Haidy. Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age. London: UCL Press, 2018.

[3] Ollman, Leah. “Commentary: I Visited Four Reopened Art Galleries. The Experience Was Not What I Expected.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, September 16, 2020. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2020-09-16/art-galleries-reopening-covid-los-angeles.

[4] “Culture & Community In A Time Of Crisis: A Special Edition of Culture Track.” Culture Track, September 17, 2020. https://culturetrack.com/research/covidstudy/.