Anton Repnikov is a senior undergraduate student at Northeastern University, pursuing a B.S. in Chemical Engineering and Physics.

VoCA is pleased to present this blog post in conjunction with Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History, Gloria Sutton’s Spring 2020 Honors Seminar, The Art of Visual Intelligence at Northeastern University. This interdisciplinary course combines the powers of observation (formal description, visual data) with techniques of interpretation to sharpen perceptual awareness allowing students to develop compelling analysis of visual phenomena.

The opioid epidemic has reached all corners of the United States, mercilessly claiming thousands of lives as it continues to fester throughout. Victims of the crisis are often left devastated and their stories are lost, smothered, or smeared. The sensitivity around the issue caused by grief, fear, and shame forms a social stigma that makes conversation about opioids and addiction difficult. The stigma facing those affected by the opioid crisis and the subsequent silencing of victims leads to a social neglect that makes wounds harder to heal, both on an individual and societal scale.

The exhibition Human Impact: Stories of the Opioid Epidemic at Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton, MA, curated by Beth McLaughlin, helps to bring the struggle faced by many Americans to a new light. Rather than collecting existing works from which to create a story, McLaughlin commissioned 11 craft artists to create new works inspired by conversations with local victims of the opioid crisis[1]. Personal experience with the opioid epidemic was not required on behalf of the artists, and each one was selected based on the presented portfolios and mission statements, drawing from a wide range of styles and careers. Once selected, the group of artists gathered in Brockton for substance use training by the local High Point Treatment Center and were then paired up with a community member or family that had been deeply impacted by the opioid epidemic. The museum and treatment center were initially worried about finding volunteers to talk to the artists, but it turned out that people really wanted to share their stories, especially families that had lost a loved one[2]. After conducting interviews with the victims of the opioid crisis, artists independently constructed their pieces with only occasional check-ins on progress from McLaughlin. The resulting artworks come together to form an accessible outlet and emotional catalyst for the epidemic, providing space for victims and allies alike to process their experiences with the crisis and inspire a sense of relatability, hope, and understanding.

View of Human Impact: Stories of the Opioid Epidemic at the Fuller Craft Museum from the entrance to the exhibition. From left to right, Deborah Baronas’s Beyond Stereotype, John Christian Anderson’s Sacrificial Lamb, Jodi Colella’s Once Was (Remembrance), Steve Loar’s Collateral Damage, and Jessica Skultety’s Unsaid are visible. Image courtesy of Will Howcroft Photography.

The exhibition called together artists, treatment center employees, community members, and even local students to help transcribe the interviews with victims. The unprecedented nature of the project presented the biggest obstacle for McLaughlin. “Naturally, without an existing roadmap, it was challenging and at times nerve-wracking,” she says[3]. But despite the pressure to do justice to the weighty subject matter, when it all came together, the show was exceptionally well-received. “There was not a dry eye in the house that night,” McLaughlin recalls when describing the private viewing held for the interviewed families and artists before opening week. Initial doubts about the project were sharply countered by the thirst people showed for approaching these difficult issues. “People really appreciate institutions that offer the outlet.”[4]

Contemporary craft arts are a perfect medium for the expression of such a painful and personal topic. The handmade nature of craft arts not only allows the artists a physical channel for their emotion but makes the art pieces themselves feel closer and more relatable. A striking selection of large, colorful fabric installations are the first thing visitors see upon entering the exhibition, with Once Was (Remembrance) by Jodi Colella, a contemporary craft artist based in Sommerville MA, in the center. The piece consists of 3,600 handmade poppies sewn from clothing donated by opioid epidemic affected individuals, each poppy representing 200 lives claimed between 1999 and 2018.

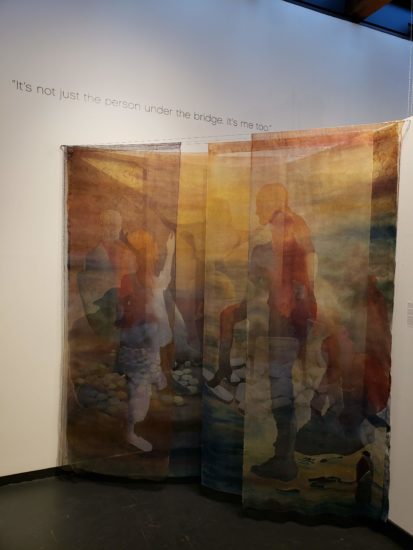

Deborah Baronas, Beyond Stereotype, 2019, Fabric dye stenciled and silkscreened on cotton and silk, 108” x 84” x 48”

Immediately to the left, Deborah Baronas’s installation Beyond Stereotype pulls viewers in with its eerie beauty. Baronas is based in Warren, RI, and works primarily with paint and textile printing to create works about hardworking American people[5]. The family Baronas interviewed had lost a loved one—a young woman who was a pleasure to be around and healthy by all appearances—to a fentanyl overdose. Baronas uses the outlines of attractive figures in their daily routines on colorful layers of hanging silk and cotton panels to express how opioids can affect anyone. The layers of scrims symbolize layers of addiction and the way people under the grasp of opioids attempt to conceal their struggles. Opioid addiction can affect anyone and victims are often very effective at hiding their dependence. As one moves around the room, the colors of Baronas’s panels seem to shift and the figures create a sense of movement. Viewers are invited to interact with the installation by standing behind the layers of scrim, and the vague outlines of people invoke a sense of relatability, as the figures can be anyone.

Steve Loar, Collateral Damage / So hard to leave what you’ve defended, 2019, Wood, reed, antique wicker, antique bed finial, bamboo, flake board, firewood, found materials, paint, dye, 67” x 46” x 29”

Further into the exhibition, the mixed media sculpture Collateral Damage / So hard to leave what you’ve defended by Michigan-based artist Steve Loar touches on the parallel nature of our lives. The mixed media piece consists of two parallel “stems” that depict life events and habits with various woods, reed, paints, and found materials that one follows from the base to the tips, with a guide to assist interpretation provided on the left. Each stem depicts the passage of time in the lives of two siblings, a brother (B, on the left) and his older sister (S, on the right). The two grew up in a family with a history of addiction and substance abuse problems, and as the older sibling, S took on the role of protecting B throughout their childhood, shown in the piece with reed coming from S’s stem and surrounding B in a hug-like embrace. Despite S’s efforts, B began experimenting with drugs in high school and once S moved to college, her ability to protect B further diminished. Shortly after, B fell into heroin addiction, represented in the sculpture by thorns protruding from his stem. B survived two overdoses before realizing that he needed to stop his addiction if he was to keep living and has since been sober. In the meantime, S began using the distance created by college as an escape from her worries about B. While there, she would turn to alcohol as an additional coping mechanism before coming to the realization that alcohol was merely a socially acceptable drug. With his piece, Loar hopes to show that although we live independent lives, we deeply affect one another. Our lives are heavily contextualized by our experience and those around us. “Every viewer brings their own ghosts to the viewing of the piece,” he says[6].

The bright, joyful colors used in so many of the pieces may at first seem surprising. However, as a foil to the painful feelings, the usage of vivid colors offers an escape from the darkness of the subject matter. Furthermore, studies have shown that opioid addiction numbs the brain and dulls the senses, causing addicts to lose the ability to see bright colors[7]. Recovering addicts often describe colors regaining brightness over time, adding an additional layer of meaning to the spectrum employed throughout the show. For example, I Cry at the Joyous Parts and I Cry at the Sad Parts, by Concord, Massachusetts-based textile artist Merill Comeau, depicts her interview subject’s escape from the grasp of heroin addiction using an increasingly colorful collage of repurposed textiles stitched together. The quilt stands over 17 feet tall, transitioning from a disorganized blur of black fabrics, to brown fabrics (including a pair of overalls the interview subject associates with her lost lover), and finally to patterns of brightly colored clothes and a golden bikini. The piece captures the fracturing of life and loss that comes with addiction along with the difficult “climb,” reorganization, and self-reflection needed for recovery[8]. Like many of the other pieces in “Human Impact”, Comreau’s work incites emotion and a sense of hope, projecting the grieving surrounding the opioid epidemic while also embodying the spirit of recovery and understanding.

Merill Comeau, I Cry at the Joyous Parts and I Cry at the Sad Parts, 2019, Garments, painted and printed repurposed fabric, sequins, thread, with hand and machine stitching, 214” x 48” x 30”

By commissioning artists to portray these stories, the museum was able to bring new attention to both individual victims and the crisis as a whole. The exhibition successfully provides a platform for many voices and tells tales of tragedy while offering messages of hope and resilience. Volunteers that came forward were given the chance to have their experiences represented in artwork and artists were able to add their own emotion to the mix. The pieces form a beautiful space that destigmatizes the matter and promotes a release of pent up feelings. “Don’t be afraid to tackle the big issues,” McLaughlin comments at the end of the interview. If no one tries, nothing will change.

[1] The full list of artists includes: John Anderson, Roslindale, MA; Deborah Baronas, Warren, RI; David Bogus, Lexington, KY; Eva Camacho-Sanchez, Florence, MA; Jodi Colella, Somerville, MA; Merill Comeau, Concord, MA; Steve Loar, East Grand Rapids, MI; Natasha Morris, Miami, FL; Holly Roddenbery, Greenville, NC; Deborah Santoro, Groton, MA; Jessica Skultety, Phillipsburg, NJ

[2] Phone conversation between myself and Beth McLaughlin, Thursday March 19th, 2020.

[3] Phone conversation between myself and Beth McLaughlin, Thursday March 19th, 2020.

[4] Phone conversation between myself and Beth McLaughlin, Thursday March 19th, 2020.

[5] Deborah Baronas Artist Statement from https://baronasart.com/artist-statement-1

[6] From exhibition catalogue for Human Impact: Stories of the Opioid Epidemic

[7] S. Shina, Z. Lieverman, and L. Davis. Heroin Addiction Explained: How Opioids Hijack the Brain (2018, December 18th), NY Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/us/addiction-heroin-opioids.html

[8] From exhibition catalogue for Human Impact: Stories of the Opioid Epidemic