This week’s contributing author, Wided Rihana Khadraoui, is an Algerian-American writer and curator. Her interests lie at the intersection of cultural representation, arts, and politics, and she conducts research in the increased engagement and access for traditionally marginalized groups in the creative sector. She has a MSc in Comparative Politics from the LSE, and is currently studying for an MA from Central Saint Martin – UAL in Arts and Cultural Enterprise. For more about her work, go to www.widedkhadraoui.com.

Visual art is spread around the world in museums, institutions, and in the hands of private collectors. Many pieces are rarely or never seen by the public, unless visitors are willing to physically travel to the institution in hopes that the artwork is on display. Museums usually show just a small fraction of their collection, and visitors meanwhile deal with crowds in hopes of getting a glimpse—anyone who has visited Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ at The Louvre can attest to the claustrophobic experience.

In the art sector, there are two main interests: aesthetic and economic. Some of the allure of visual art is its inaccessibility. Yet digital platforms completely undermine this model—through them, ideas of ownership are radically dismantled. While the aesthetic experience can remain the same, the idea of ownership and economic prowess through ownership are destabilized. Across the sector there are several initiatives that are elevating exhibition potential.

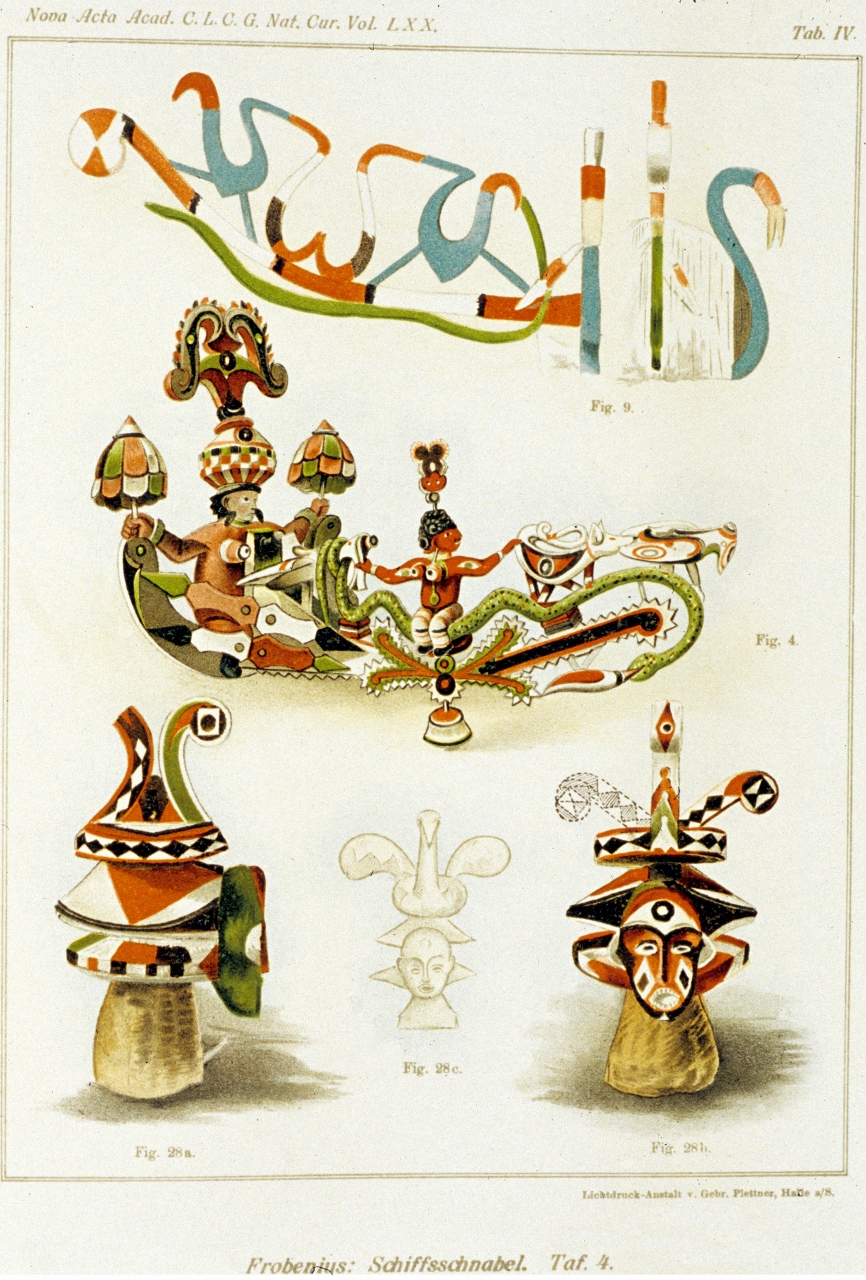

1898. Frobenius, Leo. “Der Kameruner Schiffsschnabel und seine Motive.” Abhandlungen der kaiserlichen Leopoldinisch-Carolinischen Deutschen Akademie der Naturforscher, Vol. LXX, No. 1. James J. Ross Archive of African Images, Yale University

The future of art engagement through digital heritage, overlapping platforms with more traditional physical displays, and other technology-based strategies will be more effective in engaging with a much broader and diverse audience. The potential to overhaul the way visitors interact with museums and garner more wide-ranging interest is an actuality. The inclusivity of digital platforms works to increase and enrich art appreciation and does not have to compete with a more traditional, in-person experience.

In 2016, the Museum of Modern Art was one of several major museums that launched an extensive online archive of its entire exhibition history. The archive is open to anyone interested in contemporary art and is a comprehensive account of the Museum’s exhibition history since its founding in 1929. Platforms such as Omeka project take the idea of archiving material ever further by proposing to share collections and launch digital exhibitions, as well as offering a platform to publish a complementary catalogue. Omeka can also be used to share collections, display corresponding documents, or to create user-generated archives, thereby opening up the traditional curatorial process.

The perceived threat of technology attempting to “replace” exhibitions should rather focus on how the platforms enhance each other instead. They provide an opportunity that otherwise would be impossible, or extremely difficult, for many people to experience—preservation being a great example.

The James J. Ross Archive of African Images (RAAI) at Yale University epitomized the benefits and potential of digital heritage. The collection is an accumulation of physical objects and artwork related to Africa and is a direct response to James J. Ross’ concern about the future of scholarship in classical African sculpture. The collection contains about 5,000 illustrations of African art published before 1921, giving not only researchers, curators, and experts access but also enabling the general audience to learn more about this often overlooked sector.

1888. Serrurier, Dr. L. “Dubbel Masker met Veeren Kleed uit Cabinda.” Internationales Archiv fur Ethnographie, Vol. Band I, No. Heft IV. James J. Ross Archive of African Images, Yale University.

The RAAI archive, like all collections, works to consolidate any known information of the collection, and thus streamline the process of putting together exhibitions. As Frederick John Lamp, the retired Curator of African Art at Yale University Art Gallery who regularly used multiple archives during his tenure, described it: “I could locate all possible objects in any category for possible loan to the exhibition. I could learn all the details needed on each object, such as media and dimensions. I could find the collector/owner, and all previous owners, including the person who collected it in the field. All previous publications and exhibitions are listed. Also, I could locate all in-situ photographs that illustrate the use of the object in indigenous ritual, to use as interpretive material in the exhibition.”

Archives such as RAAI have the unique opportunity to highlight missing components in the overall conversation in the visual arts, in this case the African art canon. The specific nature of the archive and its digital component allow for a more integrated approach to new modes of engagement and interpretation that have not necessarily been taken full advantage of. The potential of interactive engagement is enormous, when considering the overlap between digital archives and physical exhibitions. “I would have liked to see kiosks in the exhibition so that visitors could look up other objects of each type, and to see videos of the performance of various objects in indigenous rituals,” said Lamp. Technology-based strategies, such as digital archives, can be critical tools for not only traditional preservation, but for collection and disseminating as well, thus expanding and diversifying the conversation around art.

Swahili Women with a Fetish, Zanzibar. 1913. Stigand, Captain C.H. “East Africa and Uganda” IN Hutchinson, Walter, ed. Customs of the World: A Popular Account of the Manners, Rites and Ceremonies of Men and Women in all Countries. James J. Ross Archive of African Images, Yale University

Kristina Van Dyke, director of Pulitzer Arts Foundation, and computer engineer Frederic Cloth opened an exhibition project, Kota: Digital Excavations in African Art, in October 2015 that showcased how technology can be used for more innovative and creative exhibitions. Cloth developed a database that aggregates over 2,000 extant Kota guardian figures from Central Africa. The 2015 exhibition created a coherent aesthetic for the exhibition’s audience based on an algorithm and offered a distinctive opportunity for visitors to interact with the digital tools used for the selection of works in the exhibition.

The potential to curate shows digitally by tapping into databases and online collections is the future, as is using digital platforms to elevate and diversify audience interaction. Creating the connection between the object and the audience is one of the main roles of a contemporary curator. So this isn’t a radical redefinition of the curatorial role, necessarily; it’s the same mission, but broadened to take into account the new digital world of human experience and all of its potential.