This week’s contributing blogger, Hugh Ryan, is a writer, historian, and curator living in New York City. His book about the queer history of Brooklyn, When Brooklyn Was Queer, is due out in 2019 from St. Martin’s Press. For more, go to hughryan.org.

I was a late addition to the working group for the Artist Archives Initiative (AAI), the collaboration that created the new David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base, but I’ve been thinking for over a year about how to present Wojnarowicz’s ephemera to the world. When the Whitney opens the long overdue first comprehensive Wojnarowicz retrospective in 2018, I’ll be featuring his “Magic Box” as the heart of a companion exhibition of his ephemera at the Fales Library at NYU.

My first contact with the Wojnarowicz archive was through the Magic Box, a collection of fifty-plus discrete pieces of ephemera tucked inside a wooden crate (helpfully labeled “MAGIC BOX”), which I wrote about for Vice Magazine. In many ways, to me, the box encapsulates the complications of his entire archive: an object that straddles the line between art and ephemera; between being one thing and being many. In all of his writings, recorded musings, and conversations with friends, Wojnarowicz seems to have only mentioned the box once, in a list inside his 1988 journal, which simply says “put magic box in installation.” That installation never happened, or he left the box out of it; either way, we know very little about his intentions around the Magic Box.

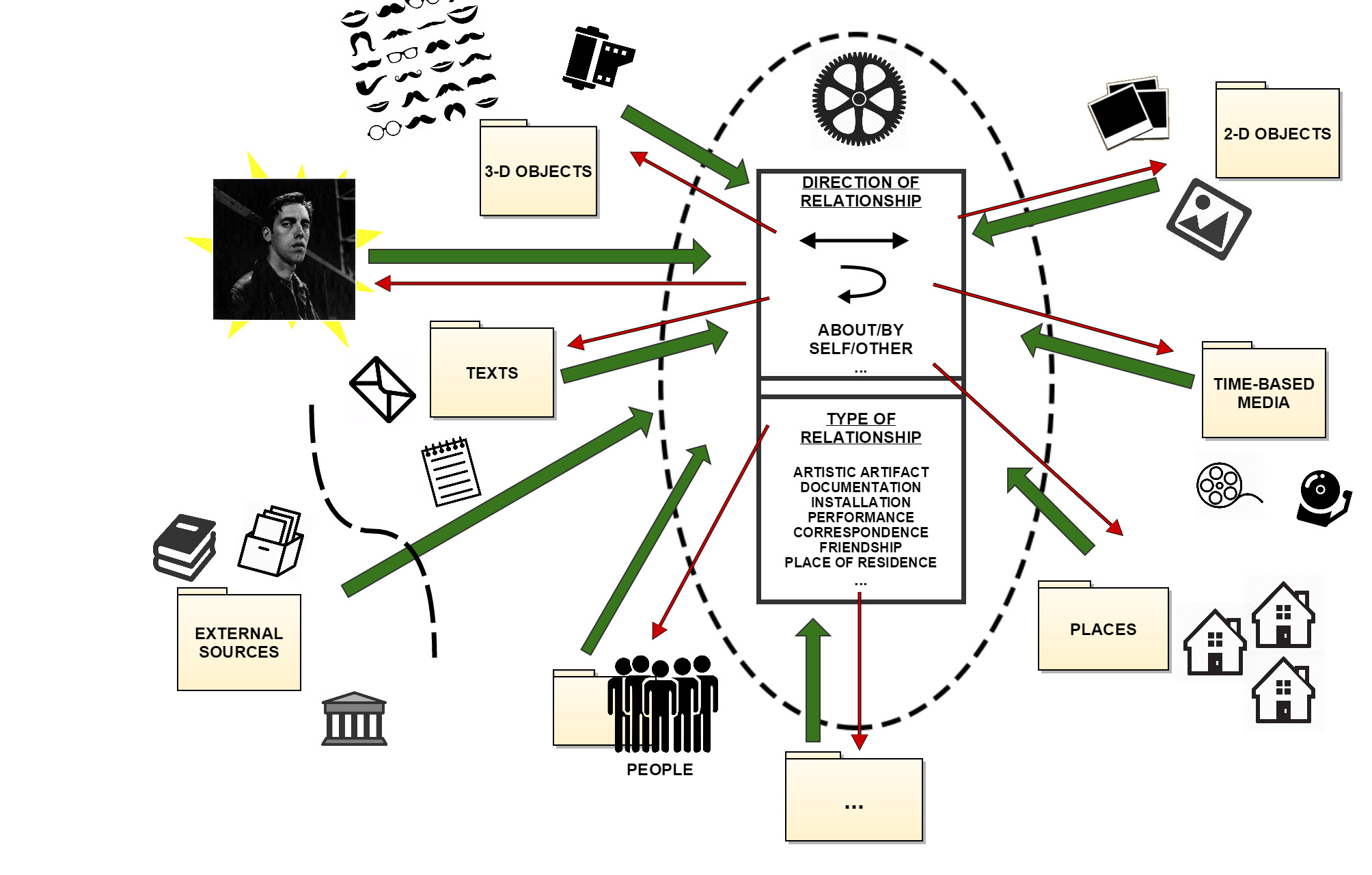

In this, the box is again representative of the archive as a whole. Wojnarowicz was prolific and hoarder-inclined, as well as being both verbose and secretive, which means he left behind an archive of many things, many works, many words, and many mysteries. The relationships between the things contained inside his archive are both obvious and confounding; ants, for instance, appear everywhere (including several plastic ones in the Magic Box), but their meaning seems to shift depending on their usage. At most, it seems possible to draw correspondences between things, to develop a web of their resemblances and correlations.

Schematic diagram illustrating complex relationships between Wojnarowicz, other people, artworks, places, and research sources. Francisco Chaparro. September 2015.

This, of course, is exactly what a well designed wiki can do best, which is one of the reasons why the computer science and data experts in the AAI working group suggested we use wiki software as the source for the Knowledge Base project. This allowed us to create a complex yet flexible structure capable of holding and drawing connections between Wojnarowicz’s vast archive of objects, symbols, art works, writings, collaborators, and ephemera. Because it is non-linear by design, interested end users can enter at any point and explore it via any path.

Someone curious about Wojnarowicz’s unfinished film A Fire In My Belly, for instance, might enter on that page, then follow a link to the entry about the controversy surrounding AFIMB being shown at the Smithsonian’s Hide/Seek exhibition. As that controversy revolved around his symbology, they might then go read about other interpretations of the film. Or perhaps they want to know more about the two men who created the Hide/Seek edit of the film, Jonathan David Katz and Bart Everly – both of whom have their own pages on the wiki.

In this way, the wiki mirrors a traditional exhibition, which creates a space filled with visual and textual information, with suggested paths that a viewer might choose to travel, but which ultimately can be experienced in nearly any order. As a curator working with Wojnarowicz’s archive, this is incredibly useful, as it lets me explore hypothetical information pathways I might try to build into my exhibition.

VoCA is pleased to present this blog post in conjunction with the Artist Archives Initiative at NYU and their inaugural project, the David Wojnarowicz Knowledge Base. The Knowledge Base is a one-of-a-kind digital information resource created to aid curators, conservators, and others who are researching the work of David Wojnarowicz. The resource was launched in April 2017. For more information, click HERE.