This week’s contributing writer, Jessica Ford, is the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Paintings Conservation at the Brooklyn Museum, holding the position since graduating from the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation in 2014.

A sampling of painted messages as captured by Google Maps. Clockwise from upper left: 2007: Our vote matters [illeg.]; 2009: Random acts of kindness = a path to humanity; 2014: Know history, know tradition, know pride, know respect; 2011: We have more in common than our differences.

I must have noticed this wall as soon as I could read, because I became very attached to a list of virtues that was painted on it in the early ‘90s. Relishing the ability to read words as complex as “charity,” I obsessively stared at the wall every time we drove past. Then, in 1992, this routine was suddenly disrupted when the wall was painted over to read “Can we all just get along?”

Still focused on the formal aspects of reading, either my sister or I asked my mom why the word “can” was used rather than “can’t.” My mom explained that it was a quote from a man who just said it that way, and eventually the broad strokes of Rodney King’s brutal arrest and the LA riots came out. We didn’t watch much TV back then or have the internet, obviously, and my young family wouldn’t normally have talked about events so far removed from our experiences. But even when I was little, I was the type of person who dwells on things. I read those words dozens if not hundreds of times that year as we drove past, and both the words themselves and the story that inspired them haunted me, even long after they were painted over with a new message. As a middle class white child, this was my first introduction to the fact that injustice based on skin color was not a thing of the past.

Twenty-five years later, when considering the importance of public murals in preparation for the Conservation of Contemporary Murals workshop in Chicago, this memory leapt to mind. Back then I may not have even understood it as art, yet because of this unassuming wall the words of Rodney King had a powerful impact on a sheltered 7-year-old in Indiana, and surely many others as well. It is in this way that public art can shape the consciousness of a community.

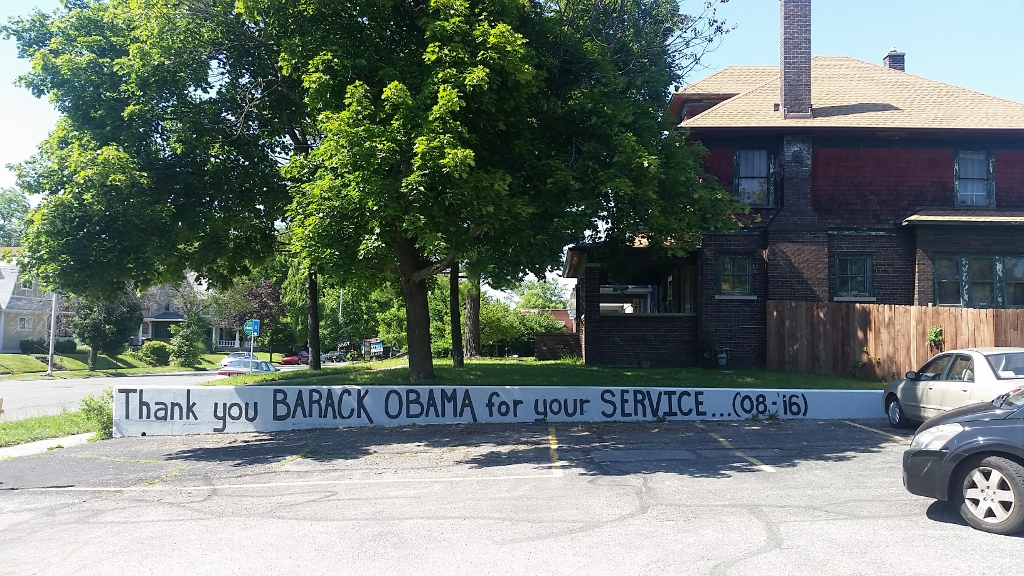

The incongruities of this particular mural only increase my fascination with it. For example, who is its community? It’s a mural more private than most, being located on a single-family residential property. At the same time, it’s so accessible that its audience includes those passing by in cars.

Following the Chicago workshop I stopped by the house to learn more and spoke with a woman a little younger than me. Her father has been responsible for all of the painted messages over the decades, including the most recent layer applied just a few months ago. However, the house is now for sale, and the family will be moving. Since learning this, I can’t help but think through the philosophical discussions from the Chicago workshop with this College Ave. mural in mind. If a chance for preservation arose, what would that look like? Since its design is directly communicative, does the mural’s value fall on the (potentially) last message, in theory justifying “freezing” the mural as it is? Or does the message become stale, perhaps even intentionally so; is it the animation of the space that’s prime, regardless of who the artist is?

Practically speaking, murals are often lost when a property changes hands. The artist’s daughter wasn’t sure if there had been any deliberate documentation of the mural’s long history. There’s a strong possibility that, other than pixelated Google Maps images dating back to 2007, this artwork’s chief presence will remain within those who felt the impact of one of its messages first-hand. The conservator in me protests; thus, I hope you enjoy this post.

VoCA is pleased to present this blog post in conjunction with “Approaches to the Conservation of Contemporary Murals”, a two-day workshop that was held during the 2017 AIC Conference in Chicago. The program focused on visits to outdoor community murals in Chicago from the past half-century, in various states of preservation. Presentations and discussions by artists, community members, and conservators regarding various approaches to conservation, treatment, repainting, or renewal of these public murals were a key component. For more information, click HERE.