This week’s returning blogger, Crystal Sanchez, works on the central Digital Asset Management System for the Smithsonian Institution, a digital repository used by all of the Smithsonian’s 19 Museums, Libraries, Research Centers, and the National Zoo, and is a member of the Smithsonian’s Pan-Institutional Time-Based Media and Digital Art Working Group. And she loves media art.

For the past five years, Glenstone Museum’s Roundtable has hosted discussions that convene a carefully-selected group of leading thinkers to explore urgent and exciting topics. The intimate gatherings, comprised of approximately 12 people around a single table, are meant to foster dynamic discussion and the exchange of new ideas among experts in a field who do not generally find themselves together. Previous Roundtables have focused on the conservation of outdoor works by Tony Smith, organic landscape management, the artist interview, and art and education.

The purpose of this year’s Roundtable was to explore the many options for storing and maintaining digital assets. It served as a valuable opportunity to bring together experts from a variety of backgrounds to advance the conversation within a rapidly-changing technological landscape. In addition to the artist’s voice, specialists were gathered from the fields of conservation, open-source preservation, archives, and film, all of whom confront the challenge of digital preservation in different ways.

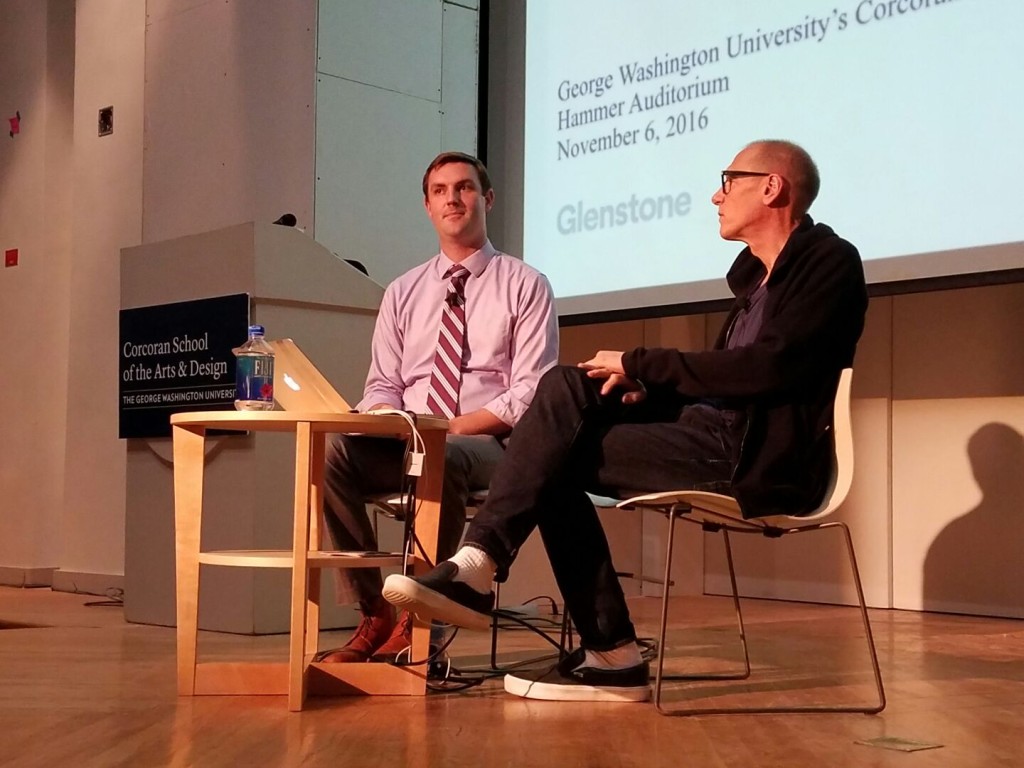

Glenstone partnered with the George Washington University’s Corcoran School of the Arts and Design as a host venue. The Roundtable took place in the Salon Doré, the Corcoran’s 18th-century French period room. The Roundtable culminated in a public program, featuring artist Christian Marclay in conversation with Glenstone’s Director of Conservation, Steven O’Banion.

Artist Christian Marclay discussing the creation, installation and preservation of his audio and video works with Steven O’Banion, Glenstone Museum’s Director of Conservation. Photo Credit: Gaby Mizes

New media, time-based media art, and artworks with electronic components can be complex to maintain in a world of rapidly-changing technologies. As more and more contemporary artists incorporate digital components into their work, fine art museums now find themselves tasked with caring for time-based media. Through the lens of art conservation, the digital landscape is riddled by unique challenges that include limited resources, digital storage specs, file-format standards, technologies, tools, staff training, anticipated change, installation priorities, and the scale of produced content.

As an emerging museum of modern and contemporary art, Glenstone also actively manages its own institutional archives, which include growing digital holdings that document the institution’s history. The video files of artist interviews, 70 interviews to date, occupy over 32 terabytes of storage space. As we gathered at the Corcoran, it was not lost on us that the event of the Roundtable itself would produce digital content to be held, managed, and preserved in the Glenstone archives.

Scene from the Digital Preservation Roundtable in the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design’s Salon Doré.

The group of Roundtable participants was small, yet representative of a wide range of fields, responsibilities, and experiences. Artists, archivists, conservators, system managers, administrators, consultants, engineers, content creators, and caretakers all work under the fine-arts umbrella, all sharing responsibility for preserving cultural heritage for access now and into the future. This intensive and wide-ranging discourse illuminated some surprising themes about digital preservation.

Digital Preservation is not a new field. It has been maturing in tangential fields from which standards, models, and tools can be adopted in building the policies and practices helpful to a museum. Just a few examples are the Reference Model for an Open Archival Information System (OAIS), NDSA Levels of Digital Preservation, NEDCC’s Digital Preservation Readiness Guides, Center for Research Library’s ISO Standard for Trusted Digital Repositories, and Library of Congress’ Sustainable Formats site.

Digital Preservation involves policies and people. Even before tackling files, systems, storage or standards, preliminary action is required. The Trusted Digital Repositories standard outlines an essential section on Organizational Infrastructure, which includes a review of governance, staffing, policies, and resources. In short, getting one’s organization to make a commitment, build a plan, detail requirements, and create timelines is crucial to effective digital preservation planning, and these steps must precede buying servers or selecting systems.

Digital Preservation is an essential business need of the organization. Although not always considered as such, spending time and resources to collect and/or create digital artworks and archives, along with their preservation (i.e., planning for short and long-term future access) is a definite part of the business needs, whether it is articulated that way or not. Framing it as such can help to provide some the resources needed.

Digital Preservation includes the care of systems and policies to manage digital content. We most often think of maintaining the content itself, but additionally we have the responsibility to manage the systems and policies, from simple to complex, necessary to care for that content. A theme of the roundtable was a focus on open-source technologies, non-proprietary formats, shared communities, and transparent documentation. Building a framework on openness and sharing gives a museum, and the field at-large, greater strength in facing guaranteed technological change in the future.

Digital Preservation means care over the entire lifecycle of the content. This means defining life cycles. How long is the retention policy for different types of assets in one’s care? Are the implications of care and the resources required for active management of that content fully understood? Do different defined life cycles exist, depending on the content?

Digital Preservation is personal and should be scaled accordingly. By personal, I mean specific to your organization, commitment, scale, resources, organizational culture, and collections. The frameworks are helpful, but there is variation within these frameworks that requires decisions personal to your organization. Even with policies in place, digital preservation should be scaled to manageable levels of care. Best practices may not be achievable for all of the content in your care, and creating scalable approaches allows for complete management of content and less backlog. Prioritizing does mean selecting, which sometimes requires making hard choices, but it is better than facing multiple hard drives, sitting on shelves and waiting to be processed.

Digital Preservation is possible. I think the most positive reaction I heard at the end of the roundtable was that all of our voices, joining together over the course of one day, helped put digital preservation in perspective. Building digital preservation commitments, policies, frameworks, practices, resources, and infrastructure necessitates a tremendous amount of work, along with a commitment to systems, resources and, most importantly, people, but this is not impossible. In fact, with the right kind of organizational commitment, it is manageable and can be scalable to the needs of any organization. Tackle it!

Digital Preservation of artwork is a specific lens whose needs shape digital preservation, art conservation, and artist engagement practices in new ways for Museums.. My favorite quote from my notes taken at the roundtable is that “with time-based media, the more you show it, the more you preserve it”, a statement which helps illuminate the slight conceptual departure of these works from traditional Museum collections care practices. Moreover, Christian Marclay’s perspective as an artist was crucial. He discussed not only the possibility of the artist’s intent shifting over time, but also learning about the preservation of an artwork in the process of continually presenting and installing it.

Digital Preservation takes a village. Forgive me for using that phrase, but sitting at the table with authorities in a variety of disciplines, it was apparent that we all bring different points of view to the discussion; we all have our own strengths, perspectives, priorities, and fears that are crucial. We each have an essential role to play in the digital preservation ecosystem. The work of building a sustainable, approachable, and specific model for the care of Digital Components of Artworks Accessioned into a Museum Collection is still ongoing. Roundtable discussions, like this successful one organized by Glenstone, lead to productive and inspiring results. A great thank you to all of my fellow participants for an engaging discussion!

The Roundtable included the following participants:

Ben Fino-Radin, Associate Media Conservator, MoMA

Dan Gillean, AtoM Program Manager, Artefactual Systems

Christian Marclay, Artist

Steven O’Banion, Director of Conservation, Glenstone

Emily Rales, Director and Chief Curator, Glenstone

Crystal Sanchez, Media Archivist, DAMS, Office of the Chief Information Officer, Smithsonian Institution

Maurice Schechter, Time Based Media Engineer, Schechter Engineering

Milt Shefter, Chair, Digital Motion Picture and Archive Project, Academy of Science and Technology Council, President of Miljoy Enterprises Inc.

Francine Snyder, Director of Archives and Scholarship, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Lauren Sorensen, Digital Media Preservation and Archives Consultant

Lori Zippay, Executive Director, Electronic Arts Intermix