This week’s contributing blogger, Mira Dayal, is an artist, writer, and curator based in New York. Her recent work has focused on language, performance, and migration.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed rewrites history. By day, she pores over archival documents of black American histories to redevelop curricula for New York City public schools. By night, she juxtaposes her own archives with fragments of famous or forgotten texts and other people’s discarded remnants in materially diverse, conceptual works. The parallel between these practices is clear and translates into a strong visual vocabulary. Rasheed’s most iconic pieces thus far are perhaps the series of propagandistic vinyl posters composing How to Suffer Politely (And Other Etiquette), which were shown at the 2016 VOLTA Art Fair in towering ten-foot vitrines. “LOWER THE PITCH OF YOUR SUFFERING,” one reads. “TELL YOUR STRUGGLE WITH TRIUMPHANT HUMOR,” suggests another. At Jack Shainman Gallery, the same works were shown alongside a series of Norman Rockwell’s 1943 World War II posters asking citizens to purchase war bonds to defend “freedom of religion” and “freedom from fear.” The juxtaposition is fruitful, not only because it places Rasheed’s work in a lineage of resistance, but also because it highlights the ways in which such “empowering” messages employ ideologies with an agenda. Who are these methods of resistance serving? Though humorous, How to Suffer Politely pointedly addresses the silencing of black bodies and the unwillingness of American publics to truly defend “freedom from fear” for all citizens who are suffering.

The stakes of Rasheed’s practice as a re-telling of history can be illuminated by Stuart Hall’s writings on cultural identity. Re-telling the past, he argues, is not only a means of stabilizing a cultural frame of reference, but also a method of producing identity, combating the erasure that colonization and migration have exerted on black bodies and histories. He writes, “identities are the names we give to the different ways we are positioned by, and position ourselves within, the narratives of the past.”[1] Embedded within such cycles of erasure and re-imagination are the power relations of colonizer to colonized, state to subject. Recontextualizing and resurfacing archival documents of black histories are then not only memorializing gestures, but also gestures towards the future of those who may use such “re-tellings” as fuel for identification and survival.

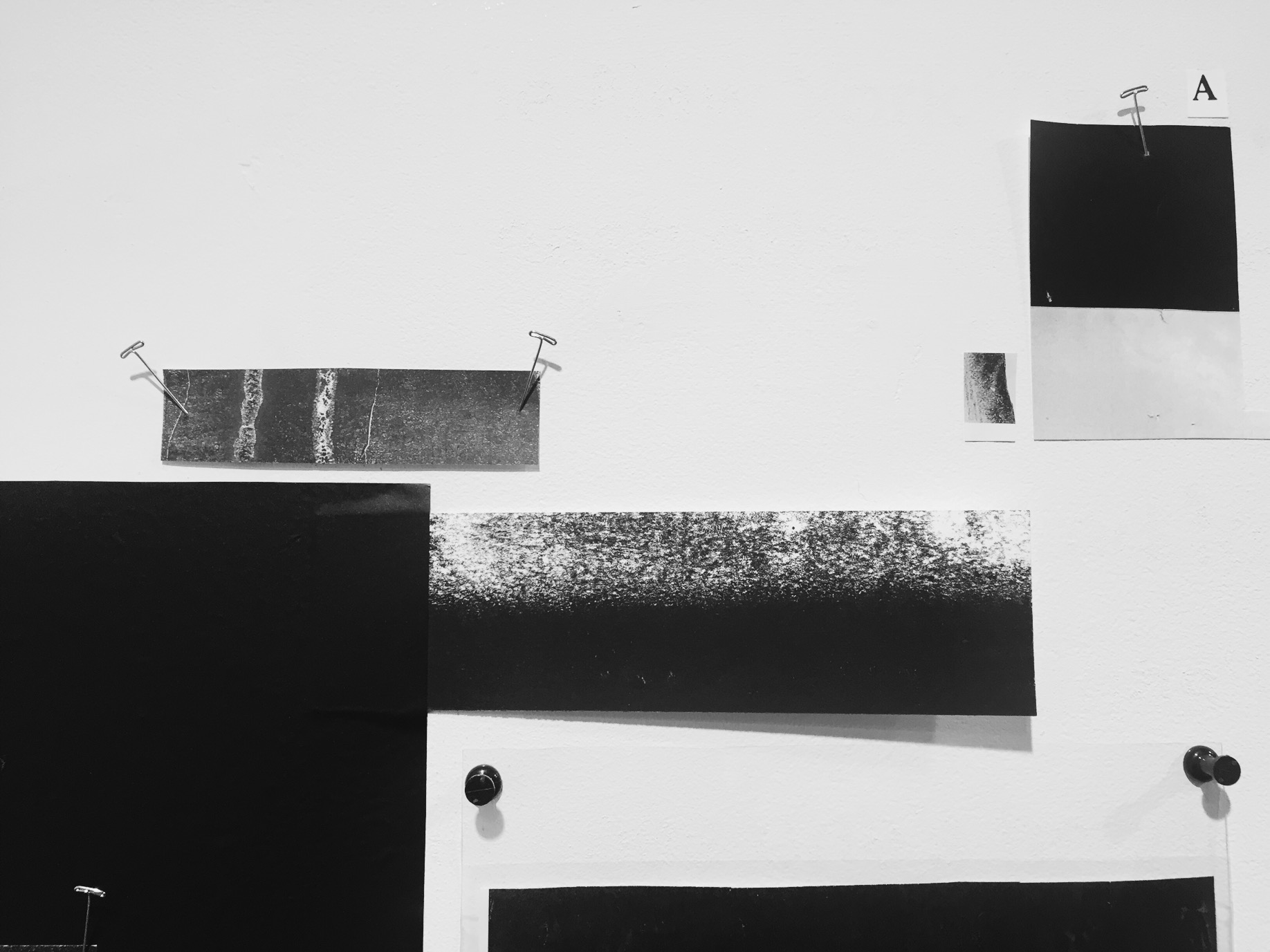

In a recent exhibition at A.I.R. Gallery, Rasheed continued her investigation of subjectivity, albeit through a more varied and indirect process. The walls of “On Refusal” are checkered with text fragments, patterns cut from the insides of envelopes, fading Polaroid photographs, and framed monoprints layered with dark ink as if printed in error on a photocopier. From afar, everything is black and white, but attention to tonal variations proves crucial to understanding the work. The scale of the text invites close inspection: read the show left to right, as a book.

Beginning at the corner of the closest wall, then, the viewer “peers voluptuously through” a network of tangled quotations. By pinning images alongside these non-sequiturs, the artist invites the viewer to imagine possible relationships. The first photograph on this wall is of a girl sitting with legs crossed in a dress. Though her neck extends out of the frame, her appearance seems formal. To her left, a quote reads, “n’t always expressed in polite company.” To fill in the gaps, one must find the source: President Obama’s 2008 speech, “A More Perfect Union,” in which he declares, “Like the anger within the black community, these resentments aren’t always expressed in polite company. But they have helped shape the political landscape for at least a generation.”

While violence is not explicitly depicted in the images Rasheed collages, it throbs beneath the surface of the work, even in the gestures of piercing the page with a pin or forcing a found, discarded image to speak again. The closest Rasheed comes to representing violence is in a video near the photograph of the girl in which a series of GIFs replay an implied act of violence. In what appears to be a courtroom, a suited white man forces down the head of a black man, whose dreadlocks tremble as the short sequence loops. But while the jerky format of the GIF seems forceful, this video is in fact nearly the opposite: Rasheed explains that the footage is from a religious ritual, a sort of voluntary cleansing. The viewer’s bias recolors each image, but this imposed truth is just as important as the original context. Near the video, the artist has pinned text saying, “I’d like you to bear this in mind as we go through the sermon.”

The tension between black and white is clear from the content of the text and videos themselves but becomes more nuanced in the textures and color fields of the monotypes and printed materials. Beginning on the first wall, Rasheed uses the format of the monoprint to comment on blackness itself. Monoprints are made by either adding ink to a bare plate or subtracting ink from an inked plate. While the final prints feel like black color fields, their process implies layers and complexities to a color often pinned as flat and unvaried. The process may also be read as content, for as Rasheed says, “printed matter was also the medium of exchange and dissemination of religious material for my father when he converted to Islam.” Method, meaning, and personal histories are intertwined, so that collage comes to represent pedagogy and present articulations of the self.

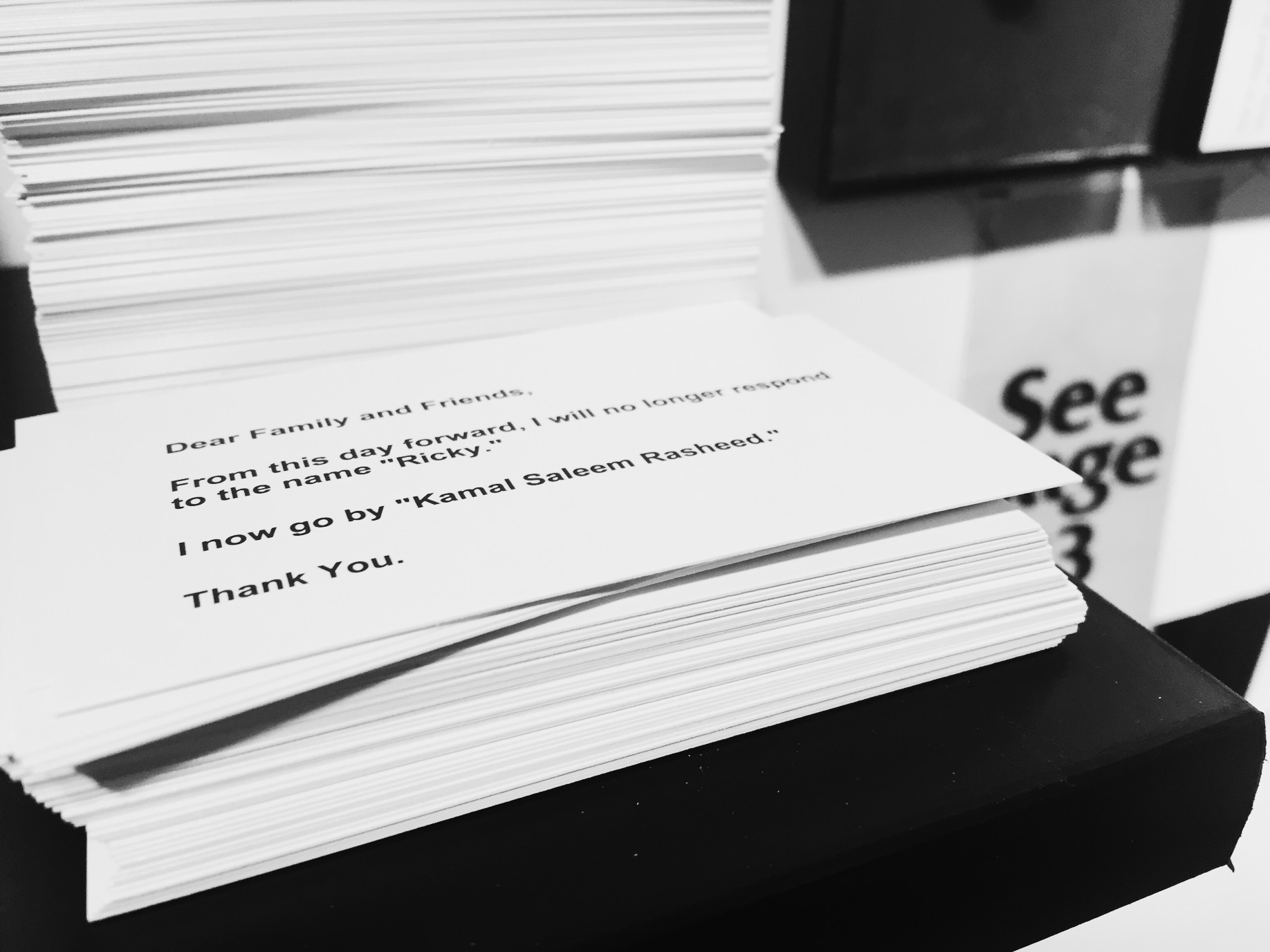

This self finally seems revealed in the business cards stacked neatly on the nearby shelf, which read in an Adrian Piper-esque fashion, “Dear Family and Friends, From this day forward, I will no longer respond to the name ‘Ricky.’ I now go by ‘Kameel Saleem Rasheed.'” Initiating a sort of rebirth or baptism, the cards invite public recognition of the person into whose history we have just stumbled. Yet the cards refer not to the artist but to her father, who literally used the cards after converting from Christianity to Islam. The cadences of “On Refusal” then emerge not only from the aforementioned tonal variations in media, but also through these bridges between divisions of identity, all revolving around an implied black subject referenced as an “elliptical self.” To point to the merging of identities is also to interrogate the ritual of naming, a somewhat arbitrary yet an essential privilege granted through hereditary, religious, and institutional rights.

Though each fragment of text or image contributes to a declaration of the fraught ambiguities of religious and racial identification, the position of the artist remains elusive. It is a daunting task to locate the origins of every point of reference. (See another phrase pinned to the wall: “S.V.H. —And I think the underlying question is, ‘Where do we go from here?'”) Circling back to the start of the show, find the framed black monotype at the start of the first wall. It appears covered with shiny black ink, but emerging from the darkness is the heel of a hand. Rasheed pulls away—or perhaps she is reaching out to draw us in. Her reaching gesture evokes an openness that may otherwise be difficult for viewers to grasp, given the density of the installation. Yet inviting others’ texts and memories into her own practice is already an empathetic gesture; it welcomes viewers’ associations, conversations, and histories. The fact that an implied community surrounds Rasheed’s work allows it to read as both personal and outward-facing, a political orientation towards a society that has taught silence and erasure as forms of etiquette.

All photos Courtesy the artist

[1] Stuart Hall, Cultural Identity and Cinematic Representation, in Framework 36, 1989 (70).