Adam Dunlavy is a PhD student at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU. After receiving his BA in art history from the University of Chicago, he has held curatorial internships at the Smart Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, as well as the Lisa and Jerry O’Brien Curatorial Fellowship at the Weisman Art Museum.

Today, art historians have all but forgotten George Ortman (1926–2015), but in the 1960s he was a prominent figure in the New York art scene, best known for his wall-hanging, three-dimensional painting-sculpture-constructions. This unwieldy description gets to the heart of the difficulty critics have had with his work. Some related it to Dada, while others related it to Geometric Purism; some called his pieces abstract paintings, while others called them constructions. The only aspect of Ortman’s work that critics ever agreed on is that his “enigmas within enigmas” defy any comfortable categorization.[1]

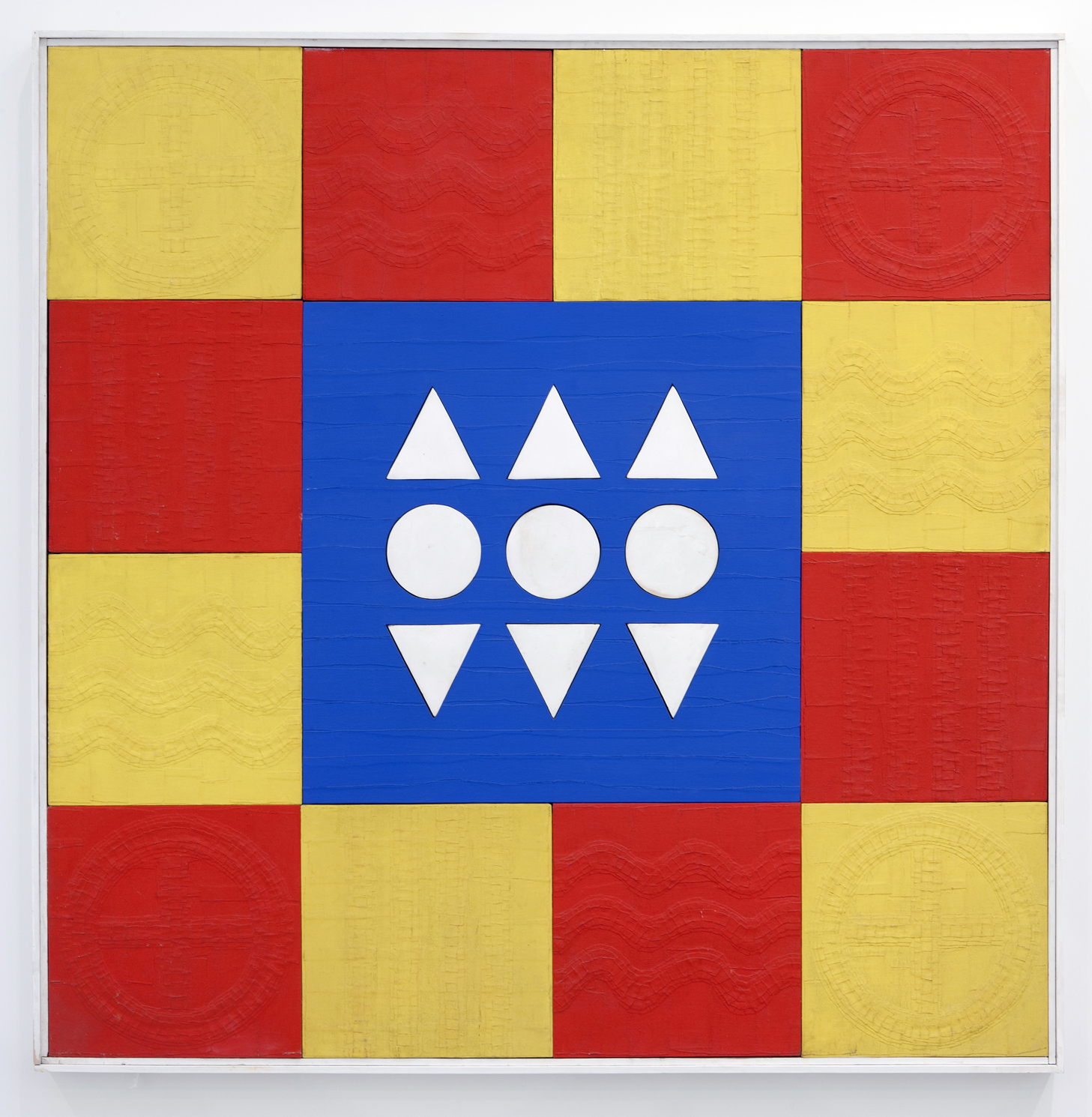

George Ortman, Tales of Love, 1959

Oil on canvas mounted on wood, plaster and collage elements, 72 x 72 in.

Estate of the artist and the Algus Greenspon Gallery

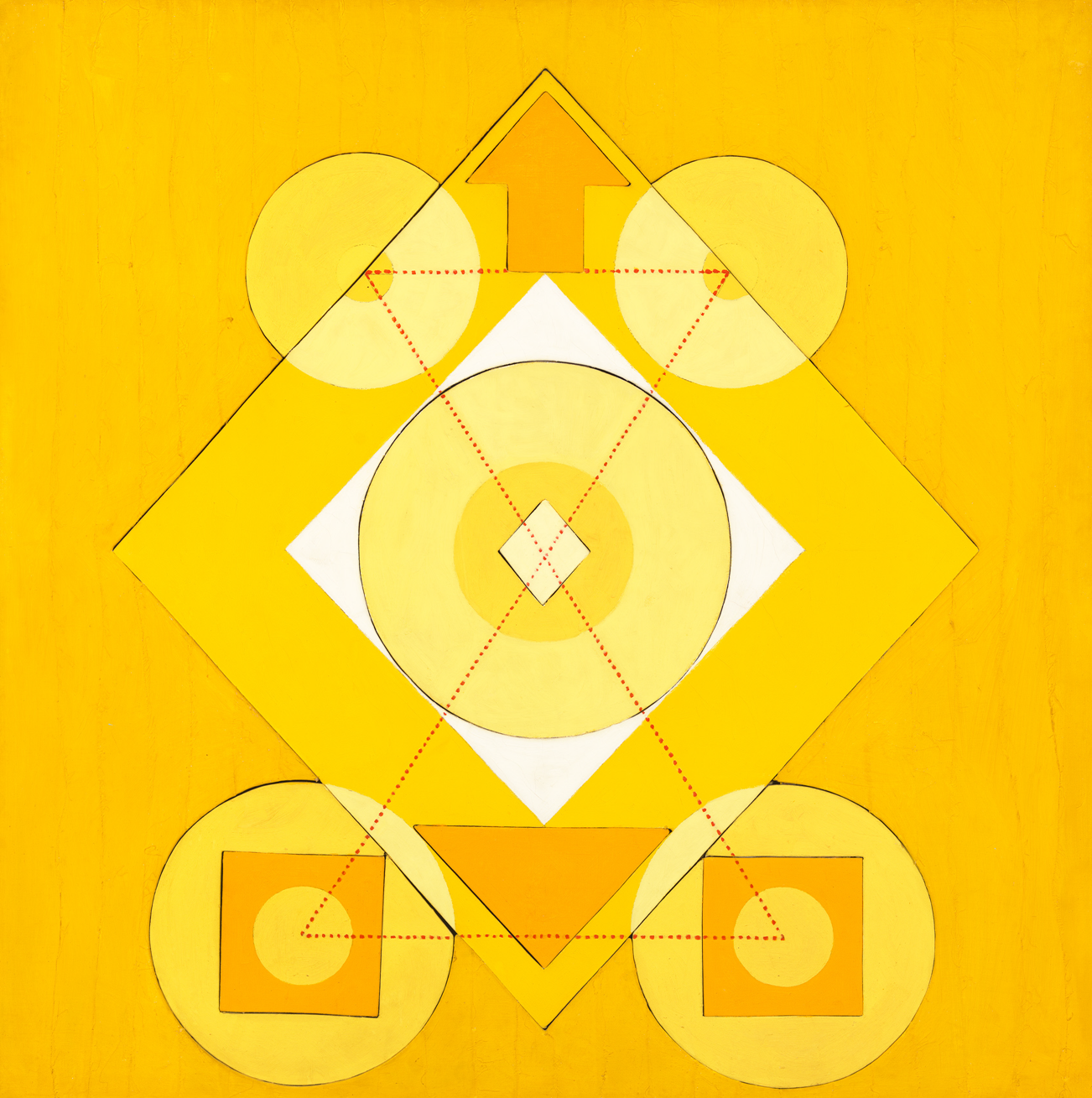

Ortman himself courted a variety of different interpretations, using what he called “general symbols”: triangles, circles, squares, diamonds, crosses, and stars. It’s possible to scan one of Ortman’s constructions without struggling to name any of its parts. And yet, it is precisely this familiarity that leads to the complexity of his work. As Ortman said, “Art is a matter…of simplifying what you begin with. I found I could express the same idea in much broader terms by using a circle instead of perhaps the female breast.”[2] Basic geometric shapes are so commonly used, and have been for millennia, that they have a practically inexhaustible set of possible meanings. Even if Ortman himself envisioned that a particular circle represented a breast, the circle would also open onto any number of other readings, from the occult to the mathematical.

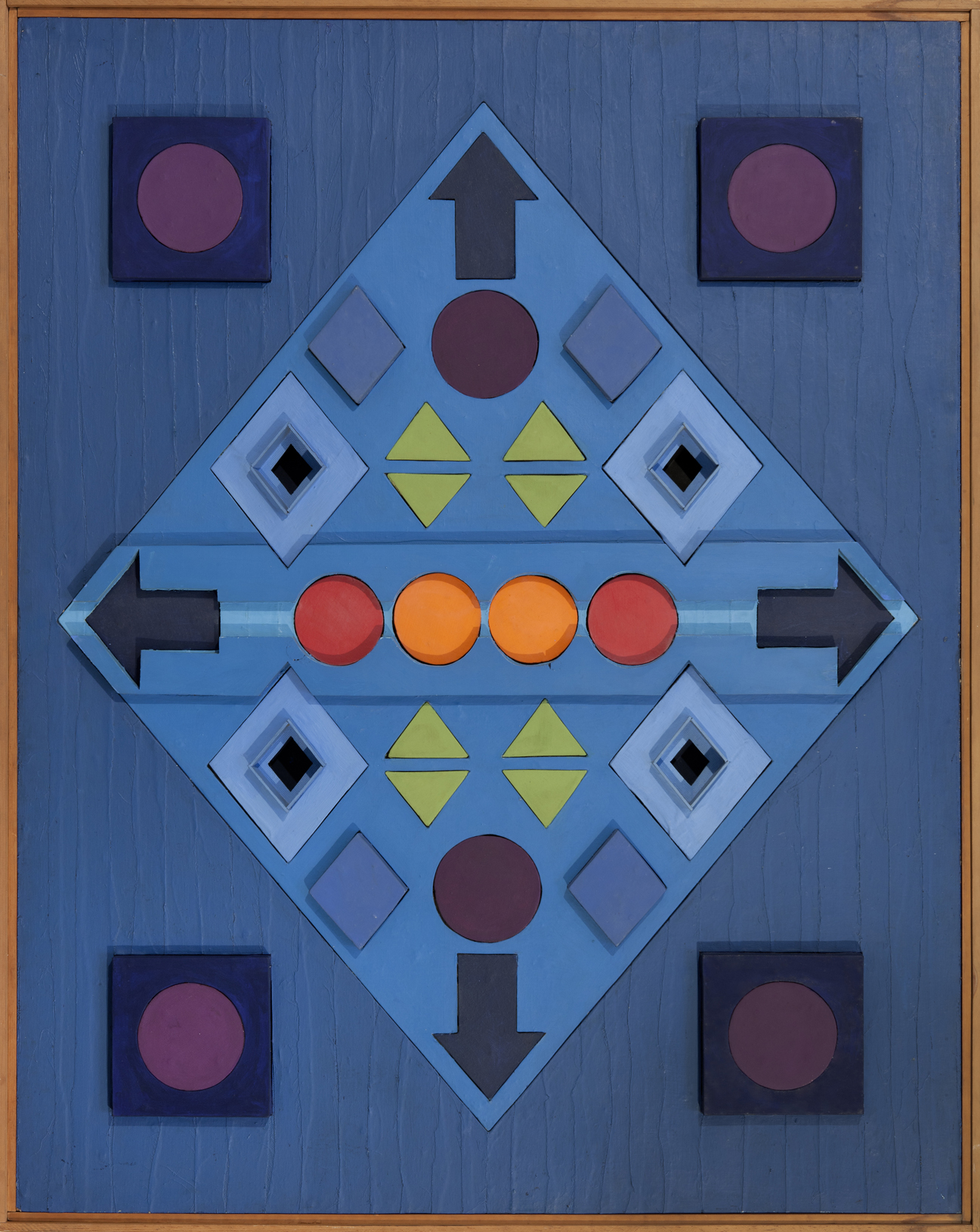

He arranged his basic shapes into intricate interrelationships, constructing them as small shaped canvases that he would then insert into larger constructions. Some shapes would be flush with the canvas, and others would project outward or inward. In other cases, Ortman painted shapes directly onto the larger canvas, or cut through the Masonite support to leave a shaped hole. Ortman arranged these shapes into mandala-like compositions that are somehow both easy to discern in their symmetry and difficult to grasp in their visual hypnotism. Different areas in his constructions contrast “smooth and rough, hard and soft, recessed and projected on the flat picture plane. The nature of the materials themselves…become[s] symbolic.”[3] The resulting constructions are symbolically, visually, and materially mesmerizing, amenable to a huge variety of different approaches and interpretations.

George Ortman, Blue Diamond, 1961

Oil on canvas mounted on wood and collage elements, 60 x 48 in.

Estate of the artist and the Algus Greenspon Gallery

By the mid-1960s, Ortman’s work had been called Surrealist, neo-Dada, Assemblage, Pop, Abstract Imagist, Hard-edge, and Minimalist. Each critic emphasized a different aspect of the work, and Ortman himself accepted all interpretations: “A painting may be extremely complex and there may be many ideas…in one picture…People have always found something that they could enjoy…and never did I really feel annoyed in any way.” For him, the more interpretations an artwork enabled, the more meaningful that work was. To demand that everyone have the same experience would only serve to limit the potential of art.

This open-ended approach flew in the face of the New York art world’s expectations for art in the 1960s. Max Kozloff conveys the discomfort Ortman’s work caused for critics: “Ortman’s wood reliefs…cast one of those spells, rather impervious to analysis…And this is embarrassing, especially when you realize that his forms could not be clearer…nor his colours cleaner…While I see exactly what is before me, and can accept their elements piecemeal, the overall presences are implausible.”[4] Finding himself unable to cast a definitive judgement on Ortman’s constructions, Kozloff’s review is more a description of his personal experience grappling with the work than it is a judgment of its aesthetic value.

George Ortman, Eve II, 1962

Oil and pencil on canvas mounted on composition board, 48 x 48 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,

gift of Arthur A. Cohen and Elaine Lustig Cohen, 72.82

This ability to defy any conclusive interpretation, however, ended in 1964 when Donald Judd published his essay “Specific Objects.” In it, Judd claims Ortman’s constructions as “preliminaries” to the new three-dimensional work he championed.[5] As Minimalism’s reputation rose, Ortman’s fell, as if the significance of his work was finally clarified. In the history of art, his practice belonged as a footnote immediately preceding Minimalism. It was practically forgotten by 2001, when the Algus Greenspon Gallery began showing Ortman’s work again for the first time in New York in thirty years. Since then, every reviewer has analyzed his practice through the lens of Minimalism. They emphasize one aspect of his constructions, namely that they are neither quite painting nor sculpture, but there is more to the sum of their parts. Following Ortman’s lead, it would be closer to say that they are both painting and sculpture. One viewer may find significance in their spatial composition, another in their play of colors (and still others in their general symbolism). Each of them can be equally correct and can serve to enrich our experience of George Ortman’s constructions.

[1] George Ortman, “Oral History Interview,” interview by Richard Brown Baker, Smithsonian Archives of American Art (September 19–November 5, 1963): side 1, page 2, tape 3.

[2] John Gruen, “Enigmas on Canvas,” New York Herald Tribune, May 10, 1964.

[3] Julie Karabenick, “An Interview with Artist George Earl Ortman,” Geoform, August 2010, 1.

http://geoform.net/interviews/an-interview-with-artist-george-ortman/

[4] Max Kozloff, “New York Letter,” Art International 4:3 (April 1962): 42-44.

[5] Donald Judd, “Specific Objects,” in Complete Writings, 1975-1986 (Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum, 1987), 183.