This week’s blogger, Emma James, is an independent curator and M.A. candidate at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College. In 2015-16, Emma organized exhibitions at the International Studio and Curatorial Program in Brooklyn, the Hessel Museum of Art in Annendale-on-Hudson, and the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in Oslo.

A Path of Safe Travel, featuring thirteen drawings by artist Sarah Oppenheimer, was on view at the Hessel Museum of Art in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY this past April as part of the first chapter of Spring 2016 CCS Bard Thesis Exhibitions. This presentation was one element within a constellating research project exploring the implications Oppenheimer’s work across various components and support systems of exhibition practice—such as the floor plan, display, and sightlines. Other elements of the project include conversations between Oppenheimer and cognitive scientist Dr. William Warren, in addition to a study session with the writer and computer programmer Alexander Galloway, which was opened to the greater student body at Bard College.

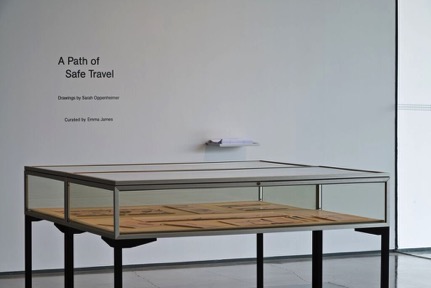

Installation view from A Path of Safe Travel, Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, April 3-24, 2016. Masters Thesis Exhibition curated by Emma James. Photo: Chris Kendall 2016.

Oppenheimer is known for making calculated adjustments to the architectural space of museums, galleries, and other art institutions. Through this, she investigates the complex, and at times dissonant relationship between personal understandings of space and the “actual space” one occupies. Beginning with quantifiable settings (from wall color to light level, temperature to humidity) as underpinning structures, she modifies these environments in ways that sharpen visitors’ attention to the locational specificity of their surroundings. Such alterations, which sometimes involve opening the wall or floor of a pre-existing structure, provoke visitors into mentally re-calibrating their position within the building. Provided with new architectural and positional knowledge, visitors are then prompted to consider this compounded perspective as they pass through the building, re-grafting a diagrammatic understanding of how the space is organized.

Re-tracing an exhibition in this way frames it within architectural terms: the role of a static viewer is perpetually displaced by that of a moving inhabitant, who is a subject unfolding in space and time. This development involves thinking of exhibitionary space in relation to both its administrative functions and adjacent environments— to consider, for example, the vast amounts of time, money, and resources regularly spent on visually divorcing the interiors we experience from their functional infrastructure, rendering them as spaces of display well in advance of the “white cube.”

The drawings on view in A Path of Safe Travel extend from Oppenheimer’s ongoing investigation into the notion of a “switch” or pivot, a variable condition that affects flows of movement in the built environment. Like machines, or tools for visualizing her research, these drawings comprise light studies and moving parts. They also parallel an ongoing body of research conducted through digital platforms, in which the artist employs customized software to trace reflected sightlines across rotating glass planes. Oppenheimer is currently investigating such questions as an artist-in-residence at the Wexner Center for the Arts, and has recently begun working with the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Ohio State University.

Installation view from A Path of Safe Travel, Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, April 3-24, 2016. Masters Thesis Exhibition curated by Emma James. Photo: Chris Kendall 2016.

In contrast to the mutability of the algorithm, the physical drawings affix a particular point in Oppenheimer’s research process to a particular time and space, marking a nexus of investigation within a larger trajectory. The exhibition marks a site of focused attention that is conducive to the mode of looking that her work engenders. For Oppenheimer, one does not begin by thinking in terms of an empty room, but rather by locating a set of given conditions that are, in a sense, already whole and complete.

What might it mean to re-think the act of walking through a museum? Installed in the entryway gallery of an enfilade, A Path of Safe Travel was the first and last exhibition visitors encountered, bookending those that fell in between. A floor plan diagram, made in collaboration with Oppenheimer, mediated between the drawings’ content and their physical display structure: two vitrines within a room that itself resembles a display case, with a glass wall dividing the museum’s lobby and the gallery. Below the vitrines, a darker square of concrete in the gallery’s center is a scar of an earlier attempt to mend the floor’s surface. While unintended, the batch of concrete mixed for this repair was slightly darker than the original, producing a discrepancy that appears to the viewer like a naturalized design element. Unless so directed, the viewer would remain unaware of this history when encountering the space. This square, however, provides the means by which the two vitrines bearing Oppenheimer’s are positioned, and is pointed to as well in the diagram.