Returning blogger Eddy Colloton is a second-year graduate student in the Moving Image Archiving and Preservation M.A. program at New York University. He is currently performing research on his thesis project, which will focus on the preservation of video installations created by the artist Buky Schwartz.

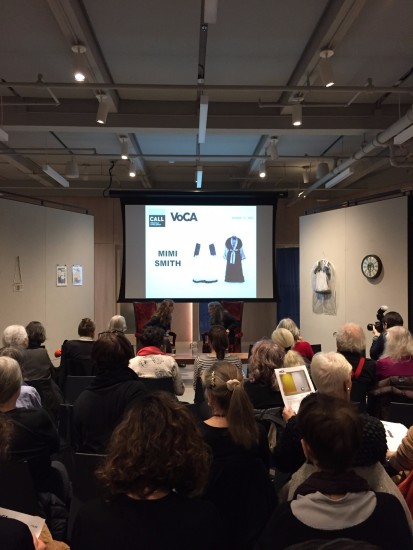

On December 9th, 2015, I walked into the Joan Mitchell Foundation Education and Research Center without knowing much about artist Mimi Smith. For the past three years, Mimi Smith (pronounced Mim-ee) has been part of the Joan Mitchell Foundation’s Create A Living Legacy (CALL) Initiative, working with legacy specialists Allison Schooler, Catherine Czacki, and Denise Schatz to collect information on the artist’s personal archive of artwork and documentation. This project has resulted in an active database of the artist’s works, one that links information and images of her extensive inventory of drawings, installations, and sculptures with the physical location of those pieces in the artist’s studio. Smith, who has spent the last few years – as she puts it – “learning how to be a dead artist,” was clearly relieved that her archive will now be easier to understand and preserve in the future. For this event, she sat down with Christie Mitchell, VoCA program committee member and curatorial assistant at the Whitney Museum, to discuss the singular experience of reviewing and cataloguing her life’s work.

Mimi Smith is perhaps best known for her Steel Wool Peignoir (1966), a modified lingerie dressing gown with steel wool lining the cuffs, sleeves and hem. Typically exhibited on a hanger, Peignoir functions as sculpture, not fashion; hung on a gallery wall or behind a vitrine, the viewer is confronted with the implications and intent of the work. The confluence of delicacy and glamor associated with a peignoir and the violent acrimony of steel wool challenges preconceived notions that typically associate the feminine with softness or fragility.

Mimi Smith is perhaps best known for her Steel Wool Peignoir (1966), a modified lingerie dressing gown with steel wool lining the cuffs, sleeves and hem. Typically exhibited on a hanger, Peignoir functions as sculpture, not fashion; hung on a gallery wall or behind a vitrine, the viewer is confronted with the implications and intent of the work. The confluence of delicacy and glamor associated with a peignoir and the violent acrimony of steel wool challenges preconceived notions that typically associate the feminine with softness or fragility.

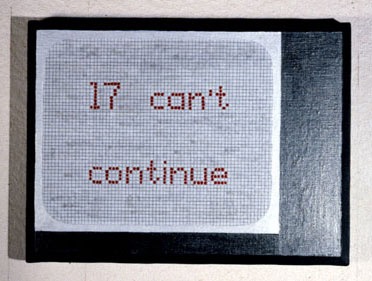

Though this work is emblematic of the artist’s continued interest in the subjects of domesticity, signifiers of femininity, and recontextualization of objects, I was struck most by Smith’s prolificacy. Too often has her oeuvre been reduced to “dresses as sculpture,” though works such as those from the artist’s System Error series certainly reiterate the need to expand the art historical purview.

These 9 x 12 inch paintings were inspired by error messages Smith encountered while learning computer programming in the 1980s. After she had started the series, painting each work using a grid pattern – or, in her words, “pixel by pixel” – others began sending her their error messages, and she painted those as well. The result is a series of 30 uniform paintings of pixelated text depicting oddly emotive, yet mechanical phrases like “Can’t do that,” “Disconnected,” and “Ready to communicate.” Despite the the “found” nature of these phrases, the artist’s personality manages to shine through this programatic and predetermined text produced by the software.

While Smith’s work is hard not to love, it would be almost impossible to resist becoming enamored with her nonchalant demeanor and charm. When Mitchell expressed surprise at the number of works from Smith’s clocks series that adorned the artist’s SoHo apartment, Smith simply responded, “Well they do tell the time.”

While Smith’s work is hard not to love, it would be almost impossible to resist becoming enamored with her nonchalant demeanor and charm. When Mitchell expressed surprise at the number of works from Smith’s clocks series that adorned the artist’s SoHo apartment, Smith simply responded, “Well they do tell the time.”

Smith is also (unsurprisingly) prolific in the medium of drawing, in which she often incorporates calligraphy. On/Off (1976) is a drawing of a light switch, rendered exclusively with the words “On/Off.” Similarly, her piece Goodnight (1979) constructs a television set out of the intertwined cursive text “goodnight.” These reflections on domestic objects, constructed through a craft often thrust upon young women, are instantly aesthetically pleasing but also provoke a deeper consideration of the artist’s relationship with this skill set and surroundings. Smith seems to take a certain pleasure in the repetitive meditation of calligraphy (hopefully, or else these works are incredibly masochistic), and given her musings on television and the nightly news, spends time in front of the tube in the evening. Yet, the combination of these subjects certainly points to a cognizant, perhaps conflicted, recognition of the construction of the domestic female identity. “It wasn’t cool to be married and have children as a feminist in New York during the 1960s and 70s,” Smith recalled. Her work has been, at times, misinterpreted as a rejection of these traditional roles of wife and mother, rather than a critique of them.

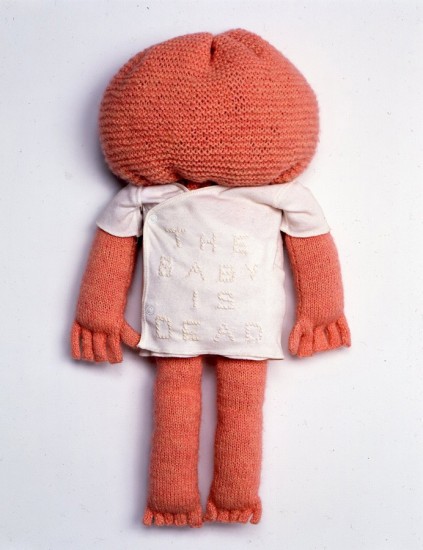

Christie Mitchell’s slide show had an image of Smith’s Knit Baby (1968), which prompted this conversation. Smith liked the idea of knitting one’s own baby, “it seemed a whole lot easier to knit a baby than have one… anyone could knit a baby, even a man, the instructions said” quipped Smith during the VoCA Talk. After the artist suffered a miscarriage, she added a shirt to the doll with “The Baby Is Dead,” written on it. This, to me, seemed to be a cathartic expression of grief, but Smith mentioned that it had been interpreted by others as a rejection of motherhood.

Christie Mitchell’s slide show had an image of Smith’s Knit Baby (1968), which prompted this conversation. Smith liked the idea of knitting one’s own baby, “it seemed a whole lot easier to knit a baby than have one… anyone could knit a baby, even a man, the instructions said” quipped Smith during the VoCA Talk. After the artist suffered a miscarriage, she added a shirt to the doll with “The Baby Is Dead,” written on it. This, to me, seemed to be a cathartic expression of grief, but Smith mentioned that it had been interpreted by others as a rejection of motherhood.

The tone of Smith’s critical examination of motherhood and marriage manages to be surprisingly positive in the face of discrimination and inequality. Maternity Dress (1966) is a great example of this. Smith felt that one of the most exciting parts of being pregnant was watching the baby grow in her belly. The maternity fashion of the time, however, concealed the change, a sad reflection of the fear a patriarchal society can exhibit toward women’s bodies. This work, then, is at once a biting attack on a chauvinistic status quo, and an outright celebration of femininity.

The VoCA Talk between Mitchell and Smith is an excellent example of how archiving materials can lead to broader access. The event was a celebration of the work completed by Smith and her CALL legacy specialists, but also an opportunity to share Smith’s talents with those who may not know about her work (like myself). Archiving and preserving artwork is not about some distant and unknown future, but the present moment. Through creating detailed inventories, digitizing photographs, and organizing Smith’s body of work, the artist, and VoCA, enable the work to be more visible now as well as in the future.

If you’re curious, please feel free to check out my twitter feed, where I live tweeted the event, using the hashtag #VoCA.

A video recording of this event is now available on VoCA’s Vimeo channel: https://vimeo.com/172626292