Brian Castriota is a Samuel H. Kress Fellow in Time-Based Media Conservation at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. He holds an MA in Art History and a CAS in Art Conservation from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University.

Many contemporary works of art exist in a constant state of flux due to ongoing changes to technology, cultural conditions and attitudes, or artists’ stated intentions. A number of papers and discussions in the joint session between the Electronic Media Group and Objects Specialty Groups of AIC this past May considered some of the practical implications of this reality for the conservation of contemporary art. Glenn Wharton’s paper “Artist Intentions and the Conservation of Contemporary Art” provided several case studies that illustrated this point, ultimately concluding that an artist’s articulation of his or her intention is not always a reliable foundation upon which to base all conservation decision-making (see Ellen Moody’s VoCA blog post “The Abandonment of Artist Intent“). This topic was reiterated by Kate Lewis in her paper “Beyond the Interview: Working with Artists in Time-based Media Conservation.” Lewis pointed to the ways current documentation practices in time-based media conservation — namely recording artists’ statements through interviews, correspondence, and informal anecdotes — can at times result in the creation of an archive of contradictions. Lewis however emphasized that such an archive should not be thrown out with the proverbial bathwater so to speak, but rather should be understood as the many facets of an artist’s intentions or preferences for his or her work, demanding empathy, flexibility, and rigorous interpretation on the part of the conservator.

John Hogan and Carol Snow also touched on this issue in their paper “Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings: Conservation of Ephemeral Art Practice”. Hogan argued that “once you define big intent you freeze [the artwork] in time,” asking conservation not to seek a definitive statement of artistic intention necessarily, but rather to use statements around “small intent” to build towards an understanding of “big intent.” While statements around intent may at times be contradictory, or may even introduce change to the work, they parallel and echo the mutable nature of the artwork itself, composed of impermanent materials or dependencies. In the same way that we recognize that many contemporary artworks constantly unfold and evolve over time and have no singular “authentic” state, these papers highlighted how conservation must similarly avoid locking an artwork to a singular statement by an artist, and instead let this living archive of intention speak to and inform future interpretations of conservation.

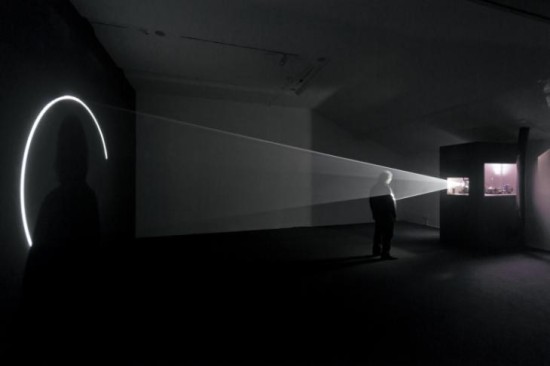

“Line Describing a Cone” 1973 by Anthony McCall (b. 1946) © Anthony McCall, courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

Another reoccurring theme of this session, particularly in the audience discussions prompted by these papers, was the conservator’s medical approach to the artwork as a living entity, and the inability for traditional theories of conservation to account for when and how an artwork might “die.” Excluding artworks where decay, entropy, ephemerality, or time/place-specificity is an explicit facet of the work’s concept, the premise of conservation hinges on the preservation and maintenance of some aspect of the artwork’s integrity or essence. While some artworks, like living beings, can only exist as a memory or in documentation after their physical demise or completion, many algorithmic, instructional, or conceptual works of art composed of changeable or variable materials do not strictly adhere to such a familiar and discernible mortal trajectory. What these works can become when they have substantially deviated from their moment of creation due to changes to their physical substance, cultural context, or the artist’s stated intention, is complex and not necessarily analogous to the life-death cycle of traditional artworks or living beings.

These talks, and ensuing discussions, underscored how far the discourse around the conservation of contemporary art has come and how the traditional practices of the conservator have transformed to accommodate artworks that themselves eschew and challenge artistic traditions. This joint session demonstrated how a critical engagement with the creators of the artworks we care for — however complex, uncomfortable, and fraught with contradictions — does not diminish or undermine conservation efforts, but rather prompts us to question our impulses, revise our theories, improve our practices, and expand our understanding of how these artworks and their multitudes might endure.