Returning blogger Tatiana Ausema is a Research Conservator at the Hirshhorn Museum and PhD candidate in the Preservation Studies program at University of Delaware. Her research focuses on the materials and techniques of Morris Louis. This is the second in a series of blog posts documenting her work on the Morris Louis Conservation Fund Archives and Conservation database.

Last August, I wrote about the initial development of the Morris Louis Conservation Fund Archive: a web-based project to document the work of the Morris Louis Conservation Fund (MLCF) and provide a resource for documentation, research, and other scholarly work pertaining to Morris Louis. In this post, I will talk about how this project intersects with the broader field of digital humanities, and the decision to use a web publishing platform called Scalar to organize and host the archive.

Although the term “Digital Humanities (DH)” may be unfamiliar to conservators, the concept it describes is central to many conservation projects: using computers to investigate, analyze, synthesize, and present information that has traditionally been investigated using other means. By definition, DH projects are often interdisciplinary, relying on the expertise of librarians, computer programmers, and subject matter experts to create innovative ways of analyzing or presenting data.

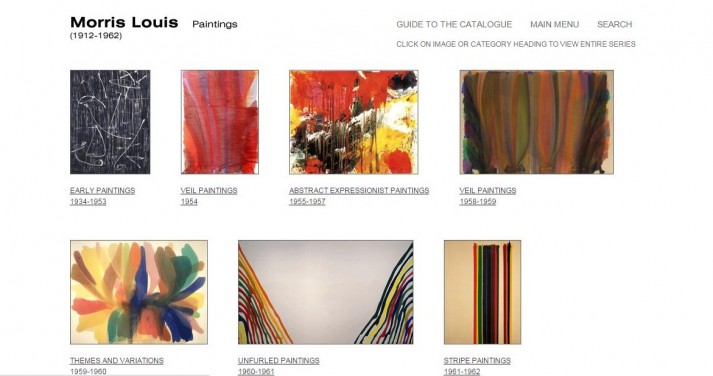

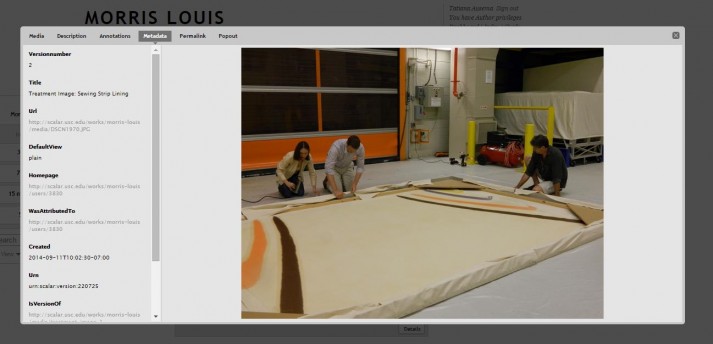

In the case of the MLCF archives, this means that we are not simply digitizing existing hard-copy records and making them accessible via a website. Instead of reproducing a digital filing cabinet with single folders for each painting, the MLCF archive allows users to explore documentation in a more fluid manner: treatments are linked to instrumental analysis, video and other born-digital documentation can be viewed directly within reports, and “tags” allow searching by a variety of keywords instead of by individual paintings. The end product is a dynamic site that allows uploading and “tagging” by registered users, allowing the resource to evolve as additional research on Louis’s materials, techniques, and working methods is discovered.

The great challenge most DH projects face is that humanities scholars are often not equipped with the technical knowledge necessary to program and develop websites, and the MLCF archive is no exception. Although I consider myself computer literate, it was not practical to learn to code, write html, and launch a website in the 18-month timeframe devoted to the project. Through the generous support of the University of Delaware College of Arts and Humanities, I attended a two-week DH “boot camp” sponsored by Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH) at University of Maryland. There I learned about Scalar: an open-source, web-based publishing format designed specifically for media-rich projects such as the MLCF archive.

Scalar is a not-for-profit web publishing tool developed by the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture. Although I tested other publishing formats such as WordPress and Weebly, Scalar was the only site that allowed both linear (chapters in a book, for example) and non-linear (“tags” or keywords) organization of data, as well as multiple formats including text documents, external websites, digital images, and video. Functionally, this means that Scalar acts as a database where you can search records by conservator, institution, treatment type, or pigment, and as a traditional “file” system where documents are organized by painting and treatment.

Since October, I have been exploring the various features of Scalar and uploading existing documentation for 57 paintings examined and treated through the MLCF. Once this information has all been uploaded and checked for accuracy, the next step will be to begin tagging and creating associations between documentation. In my next blog post, I hope to talk about how various tags and keywords are selected; different ways scholars will be able to use the completed database; and how the lessons learned from this archive project might be used to encourage other artists and artist estates to launch their own conservation archive project.