This week’s return contributing blogger, Claire Curran, recently completed her second year at Winterthur and is spending her summer work project in Copenhagen at the Statens Museum for Kunst and the National Museum of Denmark. She looks forward to beginning her third year at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

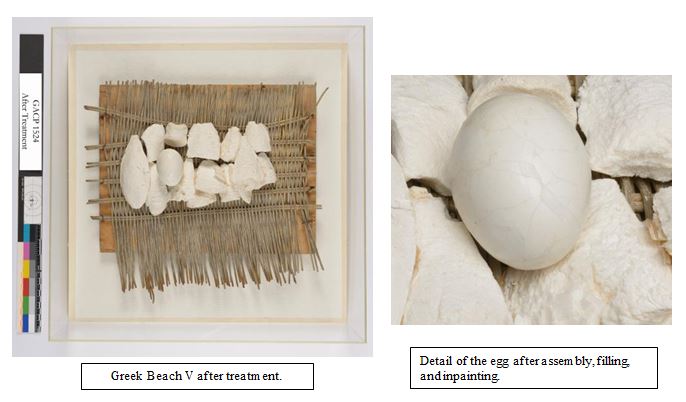

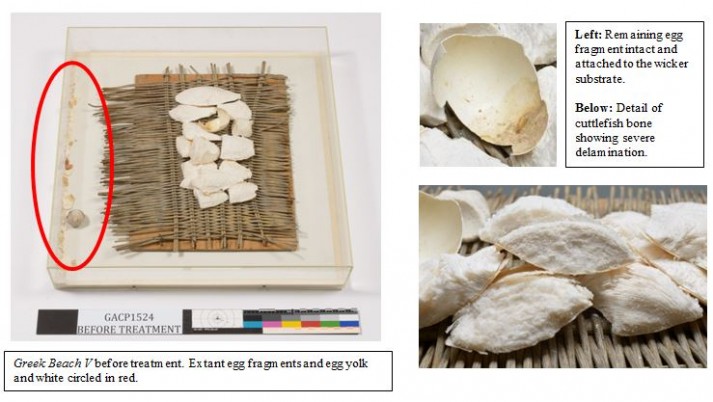

As a part of my second year specializing in objects conservation at the Winterthur University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC), I was given the opportunity to treat Greek Beach V by the artist Ilse Getz (1917-1992). Greek Beach V (1965) is a work composed of found materials that include: a plywood board, wicker, cuttlefish bones, and a chicken egg. When the work came to the WUDPAC study collection, it was fixed to a stiff canvas-covered board and enclosed within an open-backed Plexiglas display box. The condition was poor; the cuttlefish bone was delaminating with widespread flaking and loss and only a third of the egg was still intact and attached to the wicker substrate. Much of the sustained loss was sitting at the bottom of the Plexiglas box, including the dried egg yolk and white from the shattered egg. After further examination, it became clear that the condition of the bone and egg were likely a result of the presence of the plywood, which can off-gas formaldehyde. The formation of formic acid from the formaldehyde had caused accelerated degradation of the bone and egg, also known as Byne’s disease.

Greek Beach V was donated to the study collection by Werner and Sally Kramarsky in the hopes that it could be a learning opportunity for a conservation student. As a student interested in the conservation of modern and contemporary art, the project fell to me, which I was more than happy and excited to take on. Following a complete examination, I was riddled with questions. Although the artist was no longer living, I wanted to connect with a family member, friend, or gallery that might be able to offer me some answers. As the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden owns several paintings and one construction by Getz, I reached out to its staff in hopes of finding a potential candidate to interview. Steven O’Banion, conservation fellow at the Hirshhorn, graciously provided access to the Hirshhorn archives on Ilse Getz, which allowed me to locate contact information for Ilse Getz’s daughter, Patricia Preziosi. With only an address, I drafted a letter and hoped to hear back. In the meantime, I set to work on the treatment.

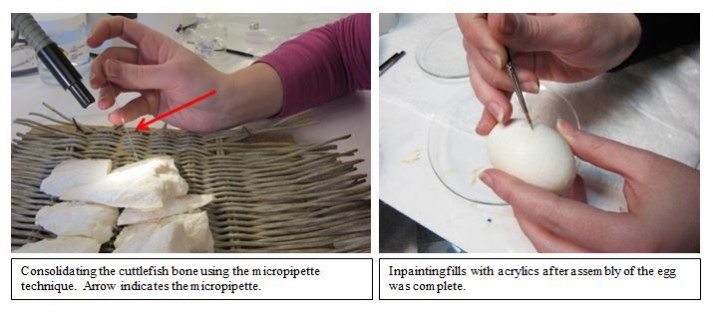

After surface cleaning, the next step was consolidation of the cuttlefish bones. Their incredibly fragile state required a slightly different approach. As they were actively flaking, applying the consolidant with a brush only caused small flakes of bone to be picked up and none of the adhesive to wick in. With a little brainstorming, a two pronged method was devised to first consolidate the exterior surface via mist consolidation followed by consolidation of the interior structure using the technique of micro-pipette consolidation. This allowed the exterior structure of the bone to be stabilized before then using a technique that would strengthen the interior structure.

Next, was the most intimidating step: the egg. Either I would need to re-assemble the egg using all extant fragments or make the difficult decision to replace it. In the midst of trying to decide what to do, I heard from the artist’s daughter. Via phone, I was able to ask many of my questions and learn much about Getz’s working methods and materials. Ms. Preziosi said that the egg could be replaced if necessary as her mother had replaced eggs on her other works when they had broken or degraded. With what appeared to be all extant fragments to make the egg whole, I felt ethically that I should at least try my hand at assembly. With patience and many hours, the egg came together with only a few losses remaining, which I was able to successfully fill and inpaint.

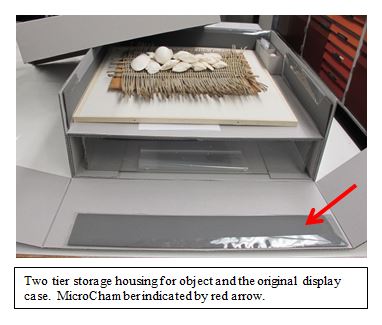

The final step was to address continual off-gassing of the plywood, which, when housed within the Plexiglas display box, could cause further degradation of the bone and egg. A two-tiered storage box was constructed with sleeves for MicroChamber boards to scavenge acidic gases, allowing the work to be stored with, but outside the display case. Were the work to be exhibited, the existing Plexiglas case would need to be altered or a new one constructed to allow ventilation of acidic gases.

The final step was to address continual off-gassing of the plywood, which, when housed within the Plexiglas display box, could cause further degradation of the bone and egg. A two-tiered storage box was constructed with sleeves for MicroChamber boards to scavenge acidic gases, allowing the work to be stored with, but outside the display case. Were the work to be exhibited, the existing Plexiglas case would need to be altered or a new one constructed to allow ventilation of acidic gases.

This project was an amazing learning experience, which had a rewarding conclusion as one of the presentations at the 2014 ANAGPIC Conference in Buffalo, New York. It allowed me to explore the unique issues to consider in the conservation of contemporary art, as well as practice the skills required for the artist interview. I feel privileged to have been able to work on Greek Beach V and happy that I could help give the work a second life.