Christie Mitchell is a curatorial assistant at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Prior to earning an MA at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU, she was a research assistant for the publication and exhibition Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface, at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego.

On a Saturday morning in the spring of 2013, I was fortunate enough to find myself sitting inside Helen Pashgian’s studio in Pasadena, surrounded by immaculately finished art objects and resin molds, listening to her speak about the scientific working method she used to produce her signature spheres. Pashgian recounted her experiments with casting resin in the late 1960s, then a recently declassified and mysterious material. With outcomes ranging from perfectly polished rainbow globes of shifting light to smoking, shattered pieces of plastic, Pashgian’s mastery of industrial materials took years of study, trial, and error.

Helen Pashgian, Untitled, cast polyester resin, overall dimensions: 8 in. diameter, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, Museum purchase, International Contemporary Collectors Fund. © Helen Pashgian. Photo by Philipp Scholz Rittermann.

I originally became intrigued with the materiality of Pashgian’s work and her scientific working method while researching for the show Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface in 2011. During my time as a research assistant with curator Robin Clark, interviews undertaken as primary research for the exhibition and catalogue were conducted with as many of the artists included in the show as possible. Clark (who attended INCCA – North America’s Artist Interview Workshop in 2013 and is now a member of their board) asked detailed questions about the working process of the artists, many of whom used finely-tuned techniques to create the stunning visual effects they desired. Whether they had worked with neon, Fiberglas, vapor-coated glass, or plastic resins, all the artists spoke of the excitement these new industrial materials had inspired, the possibilities they opened up for the exploration of human perception, and often also of the challenges the materials present today to art historians and conservators.

Because so much was unknown, the artists were at the scientific fore of pushing these materials to new limits: DeWain Valentine concocted his own formula of resin in order to create towering plastic slabs, Peter Alexander played with molds and razor-thin edges to create bands of color that dissolved into space, and Pashgian spent years building up resin layers from the inside out to make luscious, mutable spheres and panels. The fascinating, spectacular and fragile works that were created as a result physically highlight the intersection of technology and art that, retrospectively, has come to define the Los Angeles art world circa 1970.

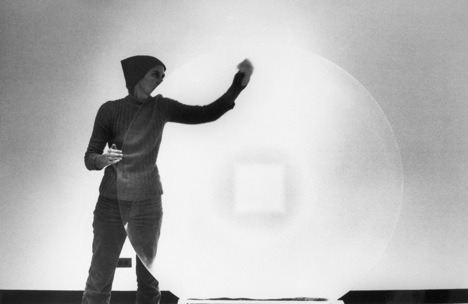

Helen Pashgian polishing a cast resin sculpture during her artist-in-residency at the California Institute of Technology, 1972.

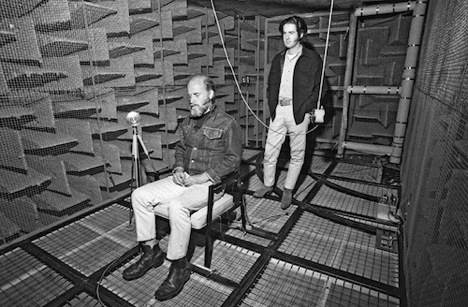

LACMA’s “Art and Technology” program, which lasted from 1967-1971, was one of the most telling and idealistic of the time period. The entire premise of the partnership – to pair artists with technological companies and institutions – underscores the ideological fluidity between art and science that became paradigmatic during those years. As Pashgian recounted when speaking of her time at Cal Tech, “I already knew that an artist and a scientist work in a similar way.”[i] These ambitious projects often ended in failures, and many never came to fruition. Even if artists and scientists work in a similar way, they often do not have similar aims.

James Turrell and Robert Irwin in the anechoic chamber during their collaboration with Garrett Corporation. Courtesy Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

But upon second thought, perhaps the Art and Technology program is not so utopian or redolent of the past after all. The recent spark of interest in this project and the conservation issues surrounding the works of this time period reveals how the idea of a mutually beneficial exchange between art and technology is more relevant than ever. For example, one of the more difficult aspects of displaying Pashgian’s early pieces is that the cast-resin medium is softer than previously thought, and increasingly prone to scratches or cracks. In order to achieve the perceptual effects that Pashgian so desires, the finish must be perfect— the aim is to be able to see into and through the work, without the distraction of a marred surface. A damaged work poses serious curatorial and conservation issues, where the original intent must be weighed against the desire to preserve the original surface of the object.

The materials used in the late ’60s and early ’70s challenge us still, whether in our understanding of how the artists used them, our concerns with conservation, preservation, and display, or simply the often unanswered questions of how, exactly, their unique properties have resulted in the objects we see in front of us. In the end, there is still much to be learned from a fruitful partnership of art, art history, and science.

[i] Helen Pashgian, “Modern Art in Los Angeles – Oral History with Helen Pashgian,” Getty Research Institute, April 8, 2010

[ii] Tuchman, Maurice. Art & Technology; a Report on the Art & Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967-1971. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Distributed by the Viking, New York, 1971.