This week’s contributing writer, Margaret Graham, is VoCA’s Program Coordinator and a freelance art critic for the Brooklyn Rail.

On the evening of July 11, 2013, VoCA hosted one of its most memorable Voice of the Artist programs to date: a film screening and conversation with artist De Wain Valentine. Held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and with the support of the Getty Conservation Institute, the event was both lively and well attended, providing a terrific counterpoint to the James Turrell exhibition on view in the serpentine galleries above.

For those who have yet to become acquainted with this particular artist and his work, here is an abridged introduction. De Wain Valentine was born in Colorado in 1936, where his early experiences polishing rocks, stripping boats, and painting cars fostered a deep interest in reflective surfaces, pellucidity, and industrial processes. Upon discovering “California Minimalist” and “Finish Fetish” artists such as Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, and Craig Kauffman in an issue of Artforum, Valentine felt a distinct attraction to and affinity with their work and, in 1965, moved to Los Angeles to join their ranks. Influenced by the seascapes and smoggy skies of Southern California, Valentine began using industrial plastics and resin to produce flawless, monumental sculptures that would reflect and distort the light and space around them. Valentine was undoubtedly a pioneer in his use of such materials, for although many of his contemporaries were experimenting with similar substances, Valentine was the only one who went so far as to develop a unique modified polyester resin that allowed him to cast colossal objects in a single pour.

Beyond their extraordinary juxtaposition of monumentality and fragility, staggering physical mass and gravity-defying translucence, De Wain’s sculptures have also become renowned for presenting the conservation community with a series of new challenges at every turn. How are conservators to treat the surfaces of these works as they age? Are they to be cleaned, polished, and buffed to machine-like perfection, or the small ripples and scratches that show the artist’s hand or mark the passage of time now part of the work? Does “perfection” mean the same thing now, in 2013, as it did in the 1970s, and if not, which form is preferable? And how, exactly, does polyester resin change over time, and can such changes be arrested? Should they?

These are just some of the questions raised in the GCI’s fantastic documentary, “From Start to Finish: De Wain Valentine’s Gray Column.” Although the film focuses on the restoration and exhibition of a single work— an immense rectangular slab of semi-transparent charcoal resin entitled, you guessed it, Gray Column (1975-76)— it is also a testament to the Venice Beach art scene of the 1960s and 1970s, and to De Wain’s distinctly intrepid spirit, innovative techniques, and tireless pursuit of aesthetic perfection. And after a few brief opening comments from the Guggenheim’s Carol Stringari, VoCA’s Lauren Shadford Breismeister, and the GCI’s Tom Learner, the lights of the New Media Theater dimmed and the documentary sprang to life on the screen. (Rather than recounting every factoid from the 30-minute film here, I highly recommend you go and watch it yourself)

1967 Aspen artists-in-residence, from left: an unidentified child, Allan D’Arcangelo, DeWain Valentine, Robert Morris, Roy Lichtenstein, Les Levine, and Claes Oldenburg

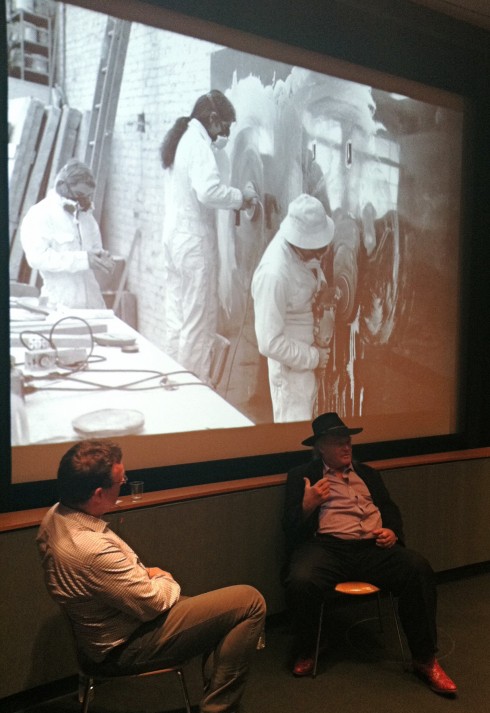

Shortly after the film wrapped up, De Wain and Tom Learner took their seats at the front of the auditorium and jumped into a dynamic discussion that ran the gamut from personal anecdotes and stories of the artist’s childhood to chemical formulas and the evolution of De Wain’s artistic process and the resulting body of work. De Wain was nothing if not enthusiastic, cheerfully recounting how his youthful interest in illustrating horses quickly shifted to a passion for fine art the first time he saw the nudes of Ingres, Rubens, and others. Prompted by a series of photographs projected on the screen behind him, De Wain spoke about the summer he spent in Aspen as an artist-in-residence alongside heavyweights such as Robert Morris, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and Allan D’Arcangelo, weighing it equally with the pivotal hours he spent as a teenager in shop class or experimenting with baking plastics in his kitchen at home (to his mother’s chagrin).

Tom then steered the conversation away from De Wain’s early artistic influences and toward his later, more ambitious projects testing toxic chemicals and collaborating with the Hastings Plastics Co. to create his Valentine MasKast Resin. Images of De Wain’s meticulous notes and mathematical calculations from over the years lead him to talk a bit about the many stages that preceded the creation of works such as Gray Column, emphasizing the supreme importance of scrupulous planning and exact computation; once the process was set in motion, there was no stopping or changing or turning back. Molding 3500 lbs of resin is an intense and incredibly dangerous labor of love, De Wain intoned, one that left absolutely no room for mistakes.

De Wain also spoke fondly of his close relationship with fabricator/restorer and long-time friend Jack Brogan and the difficult task that is maintaining the sleek, pristine surface of each sculpture, while at the same time acknowledging that conservation techniques are constantly advancing and as such we must remain flexible and open-minded to new possibilities. Tom happily echoed this sentiment, thanking De Wain for his insights and opening the conversation up to the audience.

After answering a number of trenchant questions from the crowd, one thing became undeniably clear: even now, at 77 years old, De Wain is still quite passionate about his art, and his excitement is infectious. More than anything, he wants his viewers to be able to look at his work and become involved in what he calls their “transparent colored space,” to enter into that space and sense the very real, transformative substance of the air. “When I moved to California,” he recounted, “I said that it was like you could take a chainsaw and cut a chair out of the air and sit in it.” And somehow, it seems that De Wain has achieved the impossible and done just that: defied physics and logic to create solid objects that appear to actually be made of the radiant light and tempered atmosphere of Los Angeles. It is no doubt a kind of magic, as is the brilliant restoration of Gray Column and De Wain’s other work by the conservators at the GCI, and for that, we will continue to applaud them both.

* A second Voice of the Artist event featuring De Wain Valentine and Tom Learner was held at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC on Tuesday, July 16, 2013.