In spring next year Donald Judd’s studio and home at 101 Spring Street in SoHo will open to the public after an extensive renovation led by a team of restoration specialists and New York architects ARO. As part of a program run by the Judd Foundation to promote a broader understanding of Judd’s artistic legacy through public access to the building and an insight into his worldview, last week MoMA hosted the last in a series of panel discussions about the SoHo artist. Held in the intimate Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Education auditorium on W54th Street, the atmosphere was closer to a get-together than to a formal lecture and Q&A, encouraged by the jovial and familiar panel, which consisted of Julie M. Finch, choreographer, dancer, community organizer, chef and Judd’s ex-wife and Barbara Rose, scholar, curator and art critic, both of whom lived in SoHo during the 1970s, and Andrew S. Dolkart, Director of the Historic Preservation Program and the James Marston Fitch Associate Professor of Historic Preservation at Columbia University.

Titled An Artists’ World: SoHo in the 1970s, the event began with an introduction by The Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design at MoMA, Barry Bergdoll, followed by a captivating presentation by Mr. Dolkart, who illustrated the area, its inhabitants pre-artist colony and the main events that marked the era, namely the campaign against Robert Moses’ planned expressway; the legislative initiatives such as the AIR (Artists in Residence) re-zoning; the migration of the textile industry, and the development of artist lofts that eventually pulled the area out of dereliction. Explaining why all the artists, including Gordon Matta-Clark, Claes Oldenburg and Richard Serra (some of whom remain there) moved to the area south of Houston St, Ms. Rose stated simply: “It was out of poverty.”

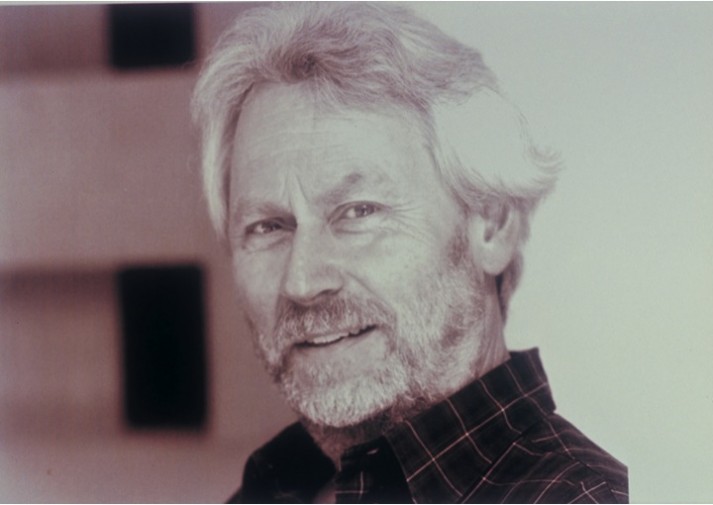

Inside 101 Sprint Street / Photo Credit: Rainer Judd-Judd Foundation Archives Image © Judd Foundation

In amongst the anecdotes and setting straight of the recent history that tends to present the artist-filled area through rose-tinted glasses – “we paid for food with art,” said Ms. Rose – the panel paused regularly to discuss the voracity of preservation and its role in the maintenance of SoHo’s character through the protection of its architecture. At this point especially, Judd’s own preoccupation with beauty and concern for well-made craft and artwork was revealed. One audience member pointed out that the campaign to protect SoHo by the artists at the time has contributed to the demise of the artist enclave and led the way to the current hive of high-profile stores. Though this may not have been Judd’s concern – he moved to Marfa, Texas in the early 70s to practice his ideas about permanent installation art and also “live in the real world” away from such an enclave – it is an interesting tension with preservation when an artist’s intent must evolve to survive. Is something lost in the process? For SoHo residents the low rent was lost. For the artists, the community disbanded. But for Judd’s own experiment at 101 Spring Street, the idea remains. Indeed, it is itself a permanent installation in an ever-changing landscape. Though Judd couldn’t have predicted the extent of the changes in the area, his respect for materials and their context, as far as their own parameters go, the Foundation’s preservation of 101 Spring St strikes me as more relevant to today’s fast and fallible culture than 40 years ago.