This week’s contributing blogger, Maria Bastos-Stanek, is the VoCA summer 2017 intern. Bastos-Stanek graduated with a B.A. in the History of Art and Architecture from the University of Massachusetts Amherst in May 2017.

On Thursday, June 22, 2017, The Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation—located in Greenwich Village in one of the few fully preserved artist residencies in New York City—hosted the discussion “Downtown Forever: Artists and Conservators in Conversation”. Co-sponsored by New York University’s Grey Art Gallery, the discussion featured VoCA Program Committee members Kate Lewis and Kendra Roth in conversation with artists Mimi Gross and Robert Whitman. The panel was moderated by Julie Martin, with an introduction from Melissa Rachleff Burtt, who curated the recent exhibition Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952-1965 at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery.

Rachleff Burtt, a clinical Associate Professor of Arts Administration at New York University’s Steinhardt school, opened the discussion by introducing Gross and Whitman, both of whose work was included in Inventing Downtown. Both artists started their careers within Manhattan’s Lower East Side, one of the rich creative centers which gave rise to and inspired Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism and other movements in the 1950s and 1960s. In Inventing Downtown, Rachleff Burtt highlights the important role artistic communities play in fostering creative talent and the innovative practice that fueled leading art movements. The primary strategy from which artists organized their creative communities consisted of artist-run galleries of all kinds ranging from co-ops to project spaces, as well as commercial galleries.

Both Gross and Whitman participated in the Downtown gallery scene, and their rich conversation with the conservators underlined the challenges of preserving art which developed out of the DIY sentiment that fueled many of the artists at that time.

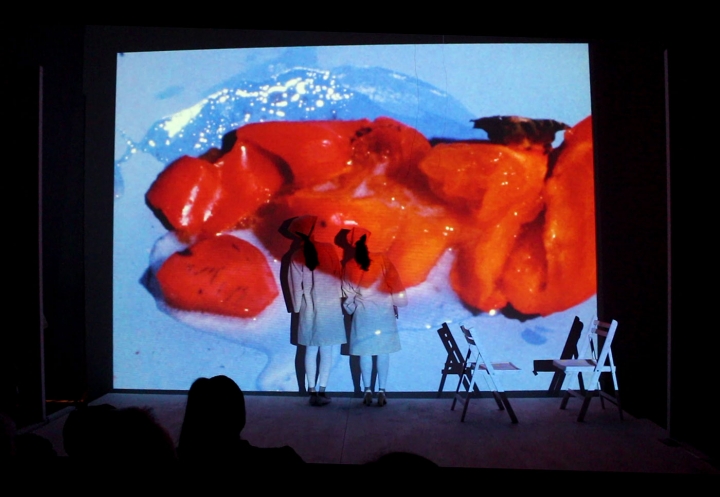

Since many of the works created during this period are unique and require individualized conservation interventions, the panel centered around specific works of art. One such work included Whitman’s 1965 theater performance titled Prune. Flat. Whitman voiced his concerns about the film, which incorporated elements of performance and theater, and acted as much as a work of art as it did the documentation from the ephemeral performance. The piece includes film footage projected on a large screen juxtaposing street scenes of Manhattan with hands cutting fruit with a knife from which confetti or other unexpected objects fall out. Whitman adds perceptual dimension to the work by including performers who walk onto the stage and stand in front of the screen. The film’s projection both conceals and reveals the performers as their bodies turn into another screen for viewing the film.

Robert Whitman, Prune. Flat., performed at Fridman Gallery, December 15–17, 2016

Image courtesy of the artist and Fridman Gallery

The work, which has been performed as recently as 2016 at the Fridman Gallery, raises many issues surrounding what constitutes a work of art, what conservation practices can be done to maintain the integrity of a work, and what others are considered revisionist. Whitman remarked that the piece’s recent transition from analog to digital did not jeopardize the work’s accuracy, but stated the intentionality with which the sound of the film projector ‘s motor’s noise remained, in digital format, to enhance and preserve the theatrical quality of the work.

Gross’s work similarly takes on theatrical dimensions that make its preservation a challenge, best handled through ongoing conversation between the artist and conservators. Many of her collaborative set designs, costumes, and props were created alongside Red Grooms, including Ruckus Manhattan (1975), a three-dimensional model of Manhattan including landmarks such as the Brooklyn Bridge and Central Park commissioned by Creative Time. Her sculptural drawings, experienced in three dimensions, cannot be fully accessed by the viewer without viewing the whole. The question persists: how does one preserve a work of art that may exist as physical objects but only claims the title of art through installation and audience interaction?

Mimi Gross, Red Grooms, and The Ruckus Construction Company, Ruckus Manhattan, 1975. Image courtesy of http://creativetime.tumblr.com

Amid these complex challenges, the conservators voiced their commitment to stewarding the vision of the artist. But, still, most conservation requires intervention, and that means altering the material qualities of a work. Some works require more than others. As Lewis and Roth noted, to understand conservation of works comprised from unconventional materials or of media-based works that suffer from deterioration or rapid obsolescence, it’s important to center the voice of the artist. A collaborative approach to contemporary art conservation often means detailed and lengthy conversations between the conservator, artist, and others. Conservators can also educate artists on how their work may change throughout time and what sorts of interventions the artist may find desirable. One artist may not find the markers of time so appealing, and may prefer more direct interventions to keep the work in the exact state during the time of its creation.

Some memorable concluding remarks came from the anecdotal conservation strategies of Gross, who recounted conserving an artwork with gusto. So, too, did the audience enjoy cross-referencing restoration strategies with the conservators. In that moment, the audience had been granted an inside-look into the collaborative practices that shape contemporary art stewardship, theory, and praxis today.